Citizen of America to Citizens of Europe

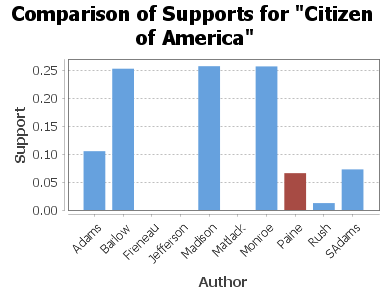

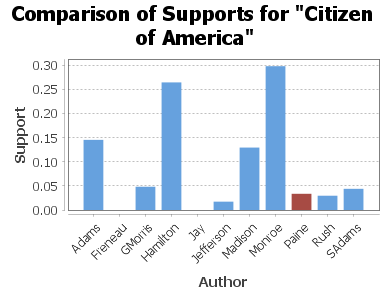

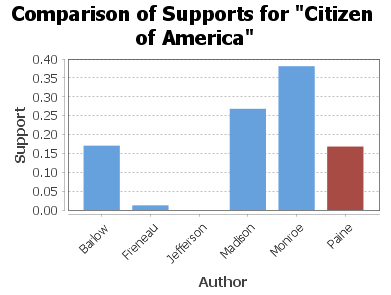

The document in French Archives (Etats-Unis, vol. 38, Part II, July, 1793 – October) is dated “Philadelphia, July 28, 1793; 18th year of Independence”. Paine’s name is penciled on the document. So context is in question, as Paine was in Paris at the time of writing. Paine may have received it from America, and it may have eventually been given to the government for printing (which would account for his name penciled on it). It does not test well for Paine at all, we would guess that it is Monroe:

A CITIZEN OF AMERICA TO THE CITIZENS OF EUROPE

UNDERSTANDING that a proposal is intended to be made at the ensuing meeting of the Congress of the United States of America “to send commissioners to Europe to confer with the ’ministers of all the neutral powers for the purpose of negotiating preliminaries of peace,” I address this letter to you on that subject, and on the several matters connected therewith.

In order to discuss this subject through all its circumstances, it will be necessary to take a review of the state of Europe, prior to the French Revolution. It will from thence appear, that the powers leagued against France are fighting to attain an object, which, were it possible to be attained, would be injurious to themselves.

This is not an uncommon error in the history of wars and governments, of which the conduct of the English Government in the war against America is a striking instance. She commenced that war for the avowed purpose of subjugating America; and after wasting upwards of one hundred millions sterling, and then abandoning the object, she discovered, in the course of three or four years, that the prosperity of England was increased instead of being diminished by the independence of America. In short, every circumstance is pregnant with some natural effect, upon which intentions and opinions have no influence; and the political error lies in misjudging what the effect will be. England misjudged it in the American War, and the reasons I shall now offer will show, that she misjudges it in the present war. In discussing this subject, I leave out of the question everything respecting forms and systems of government; for as all the governments of Europe differ from each other, there is no reason that the Government of France should not differ from the rest.

OF THE STATE OF EUROPE PRIOR TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The clamors continually raised in all the countries of Europe were, that the family of the Bourbons was become too powerful; that the intrigues of the Court of France endangered the peace of Europe. Austria saw with a jealous eye the connection of France with Prussia; and Prussia, in her turn became jealous of the connection of France with Austria; England had wasted millions unsuccessfully in attempting to prevent the family compact with Spain; Russia disliked the alliance between France and Turkey; and Turkey became apprehensive of the inclination of France toward an alliance with Russia. Sometimes the Quadruple Alliance alarmed some of the powers, and at other times a contrary system alarmed others, and in all those cases the charge was always made against the intrigues of the Bourbons.

Admitting those matters to be true, the only thing that could have quieted the apprehensions of all those powers with respect to the interference of France, would have been her entire NEUTRALITY in Europe; but this was impossible to be obtained, or if obtained was impossible to be secured, because the genius of her government was repugnant to all such restrictions.

It now happens that by entirely changing the genius of her government, which France has done for herself, this neutrality, which neither wars could accomplish nor treaties secure, arises naturally of itself and becomes the ground upon which the war should terminate. It is the thing that approaches the nearest of all others to what ought to be the political views of all the European powers; and there is nothing that can so effectually secure this neutrality as that the genius of the French Government should be different from the rest of Europe.

But if their object is to restore the Bourbons and monarchy together, they will unavoidably restore with it all the evils of which they have complained; and the first question of discord will be whose ally is that monarchy to be?

Will England agree to the restoration of the family compact against which she has been fighting and scheming ever since it existed? Will Prussia agree to restore the alliance between France and Austria, or will Austria agree to restore the former connection between France and Prussia, formed on purpose to oppose herself; or will Spain or Russia, or any of the maritime powers, agree that France and her navy should be allied to England ? In fine, will any of the powers agree to strengthen the hands of the other against itself? Yet all these cases involve themselves in the original question of the restoration of the Bourbons; and, on the other hand, all of them disappear by the neutrality of France.

If their object is not to restore the Bourbons it must be the impracticable project of a partition of the country. The Bourbons will then be out of the question, or, more properly speaking, they will be put in a worse condition; for as the preservation of the Bourbons made a part of the first object, the extirpation of them makes a part of the second. Their pretended friends will then become interested in their destruction, because it is favorable to the purpose of partition that none of the nominal claimants should be left in existence.

But however the project of a partition may at first blind the eyes of the Confederacy, or however each of them may hope to outwit the other in the progress or in the end, the embarrassments that will arise are insurmountable. But even were the object attainable, it would not be of such general advantage to the parties as the neutrality of France, which costs them nothing, and to obtain which they would formerly have gone to war.

OF THE PRESENT STATE OF EUROPE, AND THE CONFEDERACY

In the first place the Confederacy is not of that kind that forms itself originally by concert and consent. It has been forced together by chance-a heterogeneous mass, held only by the accident of the moment; and the instant that accident ceases to operate, the parties will retire to their former rivalships.

I will now, independently of the impracticability of a partition project, trace out some of the embarrassments which will arise among the confederated parties; for it is contrary to the interest of a majority of them that such a project should succeed.

To understand this part of the subject it is necessary, in the first place, to cast an eye over the map of Europe and observe the geographical situation of the several parts of the Confederacy; for however strongly the passionate politics of the moment may operate, the politics that arise from geographical situation are the most certain and will in all cases finally prevail.

The world has been long amused with what is called the “balance of power.” But it is not upon armies only that this balance depends. Armies have but a small circle of action. Their progress is slow and limited. But when we take maritime power into the calculation, the scale extends universally. It comprehends all the interests connected with commerce.

The two great maritime powers are England and France. Destroy either of those and the balance of naval power is destroyed. The whole world of commerce that passes on the ocean would then lie at the mercy of the other, and the ports of any nation in Europe might be blocked up.

The geographical situation of those two maritime powers comes next under consideration. Each of them occupies one entire side of the channel from the straits of Dover and Calais to the opening into the Atlantic. The commerce of all the Northern nations, from Holland to Russia, must pass the straits of Dover and Calais and along the channel, to arrive at the Atlantic.

This being the case, the systematical politics of all the nations, north-ward of the straits of Dover and Calais, can be ascertained from their geographical situation; for it is necessary to the safety of their commerce that the two sides of the Channel, either in whole or in part, should not be in the possession either of England or France. While one nation possesses the whole of one side and the other nation the other side, the northern nations cannot help seeing that in any situation of things their commerce will always find protection on one side or the other. It may sometimes be that of England and sometimes that of France.

Again, while the English Navy continues in its present condition it is necessary that another navy should exist to control the universal sway the former would otherwise have over the commerce of all nations. France is the only nation in Europe where this balance can be placed. The navies of the North, were they sufficiently powerful, could not be sufficiently operative. They are blocked up by the ice six months in the year. Spain lies too remote; besides which it is only for the sake of her American mines that she keeps up her navy.

Applying these cases to the project of a partition of France, it will appear, that the project involves with it a DESTRUCTON OF THE BALANCE OF MARITIME POWER; because it is only by keeping France entire and indivisible that the balance can be kept up. This is a case that at first sight lies remote and almost hidden. But it interests all the maritime and commercial nations in Europe in as great a degree as any case that has ever come before them. In short, it is with war as it is with law. In law, the first merits of the case become lost in the multitude of arguments; and in war they become lost in the variety of events. New objects arise that take the lead of all that went before, and everything assumes a new aspect. This was the case in the last great confederacy in what is called the Succession War, and most probably will be the case in the present.

I have now thrown together such thoughts as occurred to me on the several subjects connected with the confederacy against France, and interwoven with the interest of the neutral powers. Should a conference of the neutral powers take place, these observations will, at least, serve to generate others. The whole matter will then undergo a more extensive investigation than it is in my power to give; and the evils attending upon either of the projects, that of restoring the Bourbons, or of attempting a partition of France, will have the calm opportunity of being fully discussed.

On the part of England, it is very extraordinary that she should have engaged in a former confederacy, and a long expensive war, to prevent the family compact, and now engage in another confederacy to preserve it. And on the part of the other powers, it is as inconsistent that they should engage in a partition project, which, could it be executed, would immediately destroy the balance of maritime power in Europe, and would probably produce a second war to remedy the political errors of the first.

A CITIZEN OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.