By Joy Masoff

Part Two of a Three-Part Historiography

Historians are challenged to remain ambivalent when writing about multi-layered Paine. We have Paine the political strategist, the enlightened idealist and utopian, the religious heretic, the economist, the journalist, the inventor, and humanitarian. Paine was vilified, idolized and all in between.

Many early accounts of Paine’s life were scurrilous attacks that painted him as drunken, filthy, cheap, selfaggrandizing, and a wife-beater. Scholars did not offer elevating views of Paine until the late 19th century

Moncure Daniel Conway’s 1892 The Life of Thomas Paine attempted to rescue him from the rubble of distorted historical memory. Rather than quote unreliable earlier documents, Conway started anew, traveling across England, America and France to walk the streets where Paine lived, worked, fought, and faced death. Conway’s aim was to pull Paine from the historical gutter and lift him up to the pantheon of great revolutionaries.

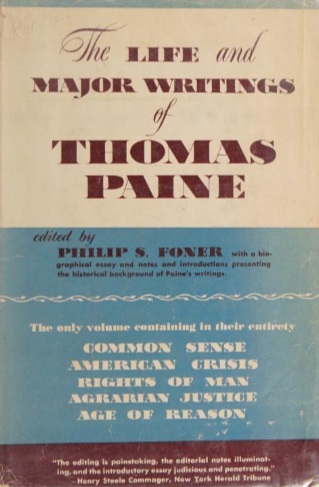

Paramount among 20th century studies was Philip S. Foner’s 1945 Life and Major Writing of Thomas Paine. Previous biographers focused almost entirely on Paine as a political disruptor. Foner offered other sides of Paine as an economist, philanthropist, deist, scientist, and poet. Foner gave us Paine as a radical ideologue grappling with the fractures between aristocracy and meritocracy as the walls between the two crumbled, calling Paine “the right man at the right place, at the right time.”

Alfred Owen Aldridge’s 1959 Man of Reason was less favorable, placing Paine on the other side of greatness as a man whose out-sized personality self-sabotaged his public career. He described Paine as having a “solitary manner of existence” and “an undeniably difficult personality.” Unlike Foner, Aldridge saw Paine as a historical accident, undeserving of his fame.

The Foner-Aldridge divide (saint or sinner) was characteristic of almost every 20th century Paine biography, revealing how little the debates about Paine’s character had changed since the early 19th century.

As the American bicentennial approached, several Paine biographies emerged. Audrey Williamson, a British theater journalist, became enamored with Paine by writing a 1963 biography of George Bernard Shaw, an admirer of Paine. Her 1973 Thomas Paine: His Life, Work, and Times unearthed new information on Paine’s metamorphosis from a young political fledgling to a polished polemicist. Like Conway, Williamson built her framework by studying the times, places and faces, and then situating Paine in the midst of them.

Samuel Edwards’ 1974 Rebel! A Biography of Thomas Paine attempted to psychoanalyze Paine, beginning with the assertion Paine had “mommy issues” that led to a distrust of women unless they were cheap blondes. Scholars were united in their dismissal of Edward’s book In fact, Aldridge, no fan of Paine, called it a work of “perversion and deception.”

The most successful bicentennial biography was David Freeman Hawke’s 1974 Paine. He gave no detours into sexual suggestiveness like Edwards, no mini-travelogues like Williamson. Instead, Hawke found new primary sources, particularly papers from the American Philosophical Society’s Gimbel Collection. He presented Paine as an inventor as well as a writer. He plumbed the entire Paine historiography, sifting through everything written — even disputed early “biographers” — with a fresh eye.

However, Hawke found it impossible to write about Paine without forming an opinion of the man and expressing it, a bias that critics of the work have pointed out. Williamson wrote with admiration, Hawke with a disapproving smirk. Williamson tried to place us in Paine’s world, Hawke in Paine’s mind. Little attention was paid to Paine as a man dependent on his connections to others, both negative and positive. The move to see Paine as more than an ideologue was beginning to occur, but the idea of important human connections was still not being made.

The most foundational bicentennial work was Eric Foner’s 1976 Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, The nephew of Philip Foner focused on 13 crucial years in the life of Paine and the fledgling United States, 1774 to 1787. Foner suggests that Paine was constantly trying to define who he was and who he would become. The topic of personhood was beginning to percolate as a line of study. Foner strived to ensure Paine was “successfully located within the social context of his age.” His acknowledgment of Paine’s personal connections to peers in his community is a link to the importance of interpersonal relationships in Paine’s life.

Foner’s work concentrated on America during its fracture with Great Britain. The unrest in France was a different beast, and Paine’s response to that revolution was different, but it was not Foner’s focus.