By Gary Berton

In the last Beacon, we introduced the shortcomings of some historians, especially as they relate to Thomas Paine. There is a preponderance of faulty historiography about Paine, and this is why our Association was founded to correct it (along with the practical aspects of uniting the various progressive groups).

Bernard Bailyn produced a book in the late 1760s, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, which represents the conservative view of history. In it, Paine is incompletely addressed, while the conservative view of the Revolution is promoted. But in his scholastic search for some semblance of truth, he stumbled upon a key work which he describes as “remarkedly original and cogent”. That work, which Bailyn refers to ten times in the book, was Four Letters on Interesting Subjects. He makes a case throughout his book how this work Americanizes the discussion of government and constitutions.

Four Letters was written by Thomas Paine. Bailyn also refers to another pamphlet written at the same time as equally influential, The Genuine Principles of the Anglo Saxon or English Constitution – that pamphlet was written by Thomas Young, Paine’s close comrade in the struggles to get the Declaration of Independence passed.

While praising these works which created the American creed of government, Bailyn minimizes Paine throughout the book, and I doubt he would have praised Four Letters to the extent he did, if he had known that Paine was the author.

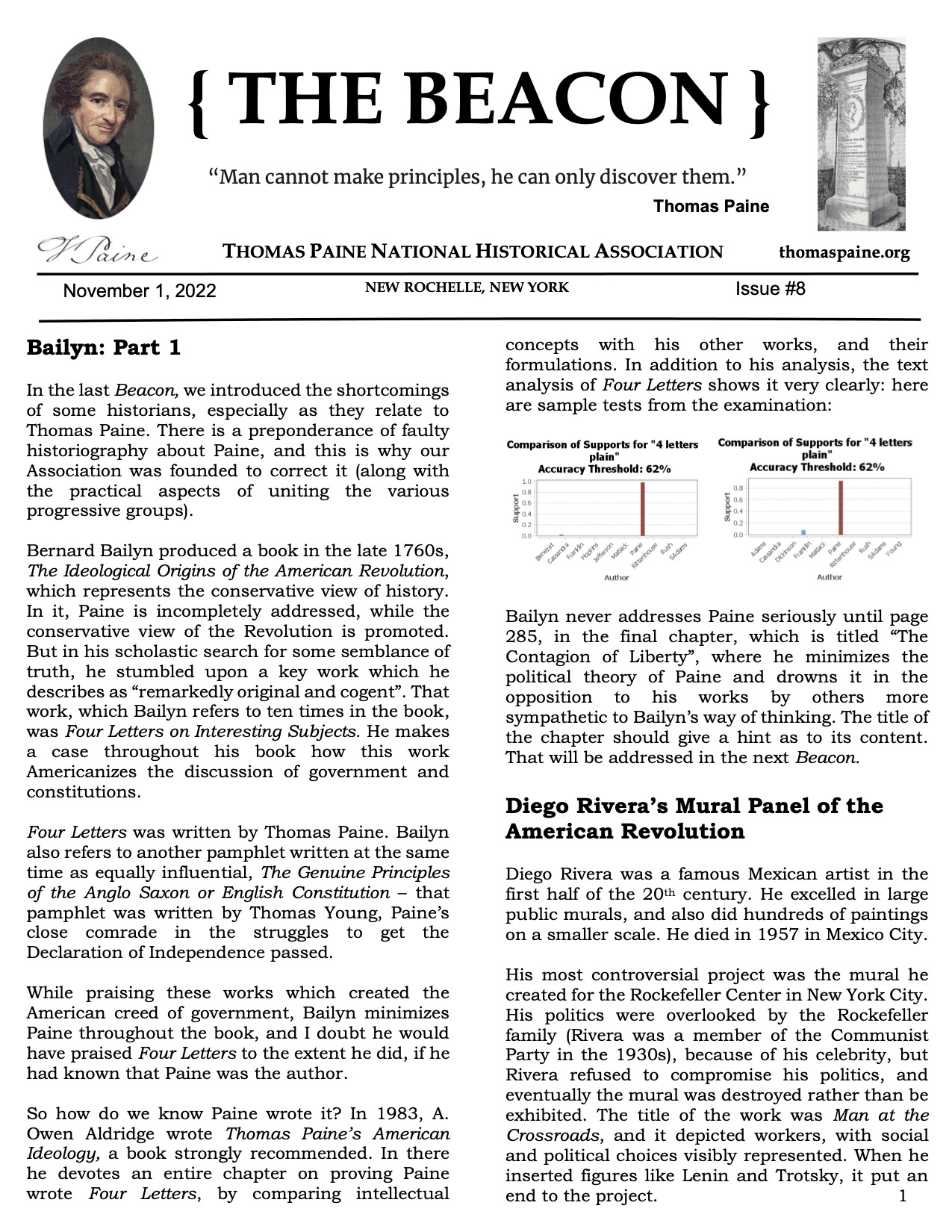

So how do we know Paine wrote it? In 1983, A. Owen Aldridge wrote Thomas Paine’s American Ideology, a book strongly recommended. In there he devotes an entire chapter on proving Paine wrote Four Letters, by comparing intellectual concepts with his other works, and their formulations. In addition to his analysis, the text analysis of Four Letters shows it very clearly. Here are sample tests from the examination:

Bailyn never addresses Paine seriously until page 285, in the final chapter, which is titled “The Contagion of Liberty”, where he minimizes the political theory of Paine and drowns it in the opposition to his works by others more sympathetic to Bailyn’s way of thinking. The title of the chapter should give a hint as to its content. That will be addressed in the next Beacon.