By Adrian Tawfik

A growing academic consensus accepts that cultural exposure to New World indigenous people profoundly shifted European society, helping to inspire the Enlightenment and calls for democracy.

Europe’s view of the New World as an exotic curiosity (satirized in Swift’s 1726 Gulliver’s Travels) became curious about those living in natural realms for fresh ideas on governance and society.

As Europeans’ contact with Native Americans increased. Writers like John Locke, David Hume, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed ideas about natural law and natural rights inspired by native ways, asserts Donald Grinde Jr. and Bruce Johansen in their 1991 Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the Evolution of Democracy.

Grinde and Johansen observe, “European philosophers functioned essentially as their nations’ early industries, importing raw materials from Native America (and other tribal societies around the world), packaging them, and then exporting them around the world as natural-rights philosophy.”

Rousseau, in particular, contrasted extreme poverty in urban Europe to the egalitarian societies in the New World. He read about the Nambicuara peoples in the Amazon and the Iroquois in North America — unlike anything that’s existed in Europe since the classical era of a Greek democracy and Roman republic.

A generation later, America’s founders, influenced by writers like Rousseau, understood Native Americans from their own direct contacts, notes Johansen in his 1990 Ethnohistory article, “Native American Societies and the Evolution of Democracy in America.” Grinde added in a 1992 Akwe:kon Press article, “Iroquoian Political Concept and the Genesis of American Government,” the strongest native influence on the founders was the six-nation Iroquois League of Nations.

The Iroquois Influence

To show their influence, Benjamin Franklin in 1753 joined a delegation from Pennsylvania signing a treaty with the Iroquois League of Nations, says Walter Isaacson’s biography of Franklin. After meeting the Iroquois, Franklin saw all Native Americans in an increasingly positive light, especially the Iroquois. He worried that their societies and lives were threatened by European immigration and imports of rum.

Franklin wanted the colonies to follow the Iroquois example. “It would be a very strange thing, if six nations of ignorant savages [sic] could be capable of forming a scheme for such a union,” Franklin said in a 1751 letter to James Parker, but “a like union should be impractical among … ten or a dozen English colonies.”

Franklin joined Pennsylvania delegates when representees of seven British-American colonies met in 1754 to discuss problems with British rule. Franklin’s “Albany Plan” proposed imitating the Iroquois League of Nations by uniting the colonies as one political body of smaller states, under the Crown.

Franklin’s Albany Plan is seen as a precursor to the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution. His “Articles of Confederation,” published a year before Common Sense, proposed a federal structure akin to the Iroquois League.

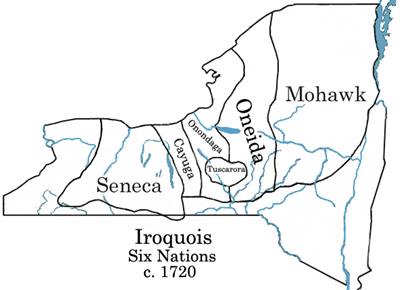

During the French And Indian War (1754-1763), Native Americans were treated as pawns of the British and French empires in their Seven Years War. The Iroquois, as significant British allies, controlled more than 75 percent of the land that now forms New York State (see map), where much of the war was fought.

Later, in May 1776, weeks before the Declaration of Independence was signed, the Continental Congress invited Iroquois leaders to Philadelphia. The Iroquois gave John Hancock, President of Congress, the name of Karanduawn, meaning “The Great Tree” (see Paine’s “Liberty Tree” poem below).

Iroquois League of Nations and the U.S. Constitution

There’s no scholarly consensus on the thesis of the Iroquois influence on modern democratic structures. Yet similarities exist between the U.S. Constitution and the Iroquois systems of government:

- Reliance on community consensus for decisions.

- Bicameral legislature (Iroquois had one for men and one for women).

- States (or Sachems) with equal voting power regardless of population.

- Systems for admission of new member states (Sachems).

- Balance of power between federal and state (Sachems).

- Separation of military and civilian leadership.

- Restricting members from holding more than one office.

- Procedures to impeach representatives (a process called “knocking off the horns”).

- The caucus, an Algonquian word, for a political organization or meeting where discussion and consensus are emphasized over voting or formal rules of procedure.

In 1988, Congress passed a resolution by the Select Committee on Indian Affairs (H. Con. Res. 331) that recognized the influence of the Iroquois on the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Enter Paine

Thomas Paine defended the Iroquois League of Nations and took their democratic ideals to a new level. Paine’s high regard for natural human rights and a republican system of government in Common Sense was highly influenced by the Iroquois example, confirmed Eric Sherbert in the 2006 Canadian Culture Poesis.

To show how governments evolve, Paine wrote the parable of a remote settlement growing into a society. His fable’s civics lesson on democracy was recognizable to the Iroquois people as well as the American settlers. In Common Sense, he voiced hope for the new world:

Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her [freedom]. – Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

For Paine, America was a land where the evils of despotism had yet to take root, says Daniel Paul in the 2007 “We Were Not the Savages: First Nations History, Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations”. After his arrival in the colonies, Paine developed a sharp interest in the “Indians” who lived in a natural state, alien to the urban and supposedly civilized life around him in England, later in Philadelphia and New York.

After the Revolution began. Paine became secretary for commissioners sent to negotiate with the Iroquois. They gathered at Easton, a town near Philadelphia on the Delaware River in January 1777. After this and subsequent personal encounters with the Iroquois, Paine sought to learn their language. For the rest of his political and writing career Paine cited them as a model for how a society might be organized.

Iroquois influences are noticeable in many of Paine’s ideas about government and society. Not being noble-born nor wealthy, having personally suffered in England from abuses of wealth and power, Paine took pleasure in witnessing a natural society without any monarchy or aristocracy or established church.

The lack of money and private property in Iroquois society intrigued Paine. The influence is evident in his 1797 pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, where Paine sharply criticized Europe’s urban poverty:

The fact is, that the condition of millions, in every country in Europe, is far worse than if they had been born before civilization began, or had been born among the Indians of North-America at the present day.

Paine added, “The naked and untutored Indian is less savage than the king of Britain.” Paine was harsh in contrasting the relatively peaceful nature of Native Americans to the “grand maniacal architect of systematic colonial oppression,” claimed Vikki Vickers in her 2006, “My Pen and My Soul Have Ever Gone Together: Thomas Paine and the American Revolution”.

As a champion of human rights, Paine held compassion for the plight of Native Americans. In an age before the permanent devastation to come, Paine was not shy in predicting “that the native Indian would be absorbed into the mainstream of American culture.” He did not foresee the violently enforced assimilation that occurred in the century after his death.

As for the Iroquois, during the Revolutionary War, they mostly allied with Britain. They trusted longstanding trade ties and promises to stop American expansion in New York. After Britain lost the war, many Iroquois resettled in Canada, chiefly Ontario. Those who stayed mostly moved onto reserved lands, such as Red Jacket negotiated for the Seneca in western New York. The Iroquois League of Nations is long gone. Their society is still teaching us about democracy.