By Adrian Tawfik

Thomas Paine in Common Sense wrote, “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” He meant it in his words, in his politics, and in his life. Paine believed in Enlightenment ideals about science. Fascinated by new technologies, Paine tried his hand at designing bridges. He’d change the world by connecting it together.

After his 1774 arrival in Philadelphia, Paine spent time with Benjamin Franklin and scientifically-minded friends. John Morton’s 2014 article “Thomas Paine & Sunderland Bridge,” in England’s Northeast Lore, says Paine “studied mechanical philosophy, electricity, mineralogy, and the use of iron in bridge building.” After the American Revolution, Paine devoted considerable energy to innovative bridge designs, which improved on existing designs.

Paine wanted to build bridges in the United States. His first attempt at bridge design was a never-built 300-foot wooden arch bridge across the Harlem River from Manhattan to the Bronx.

When he lived in Bordentown, NJ, Paine in 1786 made three small models of iron bridges, which Paine later described in his 1803 “memoir” to Congress, “On the Construction of Iron Bridges.”

“I took the last mentioned one [model] with me to France in 1787 and presented it to the Academy of Sciences at Paris for their opinion of it… I presented it as a model for a bridge of a single arch of four hundred feet span over the river Schuylkill at Philadelphia.” The Academy adopted his design principle, but only for 100-foot spans. That same year, he sent a model to Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society in England, “and soon after went there myself.”

Paine’s bridge design was being compared to The Iron Bridge in England. The first and the only large bridge made of cast iron, The Iron Bridge was built in Shropshire County by Abraham Darby III, owner of massive West Midlands ironworks. The Iron Bridge opened in 1781, reported Eric Delony in his 2000 Invention & Technology Magazine article, “Tom Paine’s Bridge.” Darby’s Iron Bridge set the standard by which any iron bridge would be judged.

After years studying iron bridge design and seeking funds to build one, Paine decided to build a large-scale model as a proof of concept. Patrick Sweeney in 2017 writes in “Tom Paine’s Bridge” for Republican Socialists UK, that funds couldn’t be raised in America, so Paine returned to England in late 1787 to construct it.

Paine began building what became the “London Model.” He described it to Congress as more than 100 feet long. The model bridge was built away from heavy traffic in a flat field “at a road junction at the edge of Paddington, north west of London.”

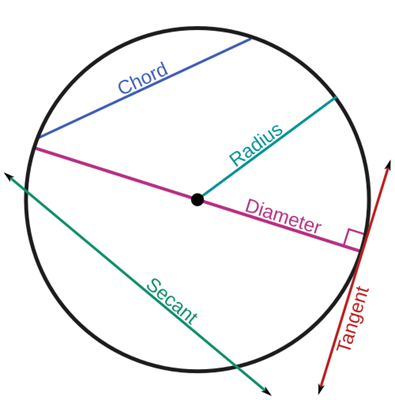

The model was constructed from cast iron. Paine’ told Congress his main innovation was the bridge arch shape, following the top circumference or arc of a circle. The arch “segment was a circle of four-hundred and ten feet diameter; and until this was done no experiment on a circle of such extensive diameter had ever been made in architecture.

”Paine’s design improved on the 1781 Iron Bridge, writes Sweeney, by offering flexibility to be as big or small, wide or narrow, high or low, “as required by the geography of the location.” The arch height and shape was not predetermined as a semicircle, then the standard design practice.

Sweeney says Paine’s solution was “based on his observation of a spider’s web, a form derived directly from nature.

He was keen on the fundamental structures of nature being the basis for our own human efforts at construction.” In essence, Paine wrote, his bridge design was:

“Taking a small section across a circle, called in geometry a cord. The bridge could be based on that cord. The starting point is to draw a large imaginary circle, then draw a cord across a section of the circle that matches the width of the river or gap one wishes to bridge. [The] key point is that the size of the circle can be infinitely varied according to the width of the gap being bridged.”

Cast iron components for the London Model were manufactured by Thomas Walker at his foundry, then transported by ship to London, says Sweeney.

Paine won a 1788 British patent for his completed London Model. His application stated, “Nothing in the world is as fine as my bridge, except a woman.”

Paine lacked the needed funds to build a full-scale bridge. His attention turned to the French Revolution and then his new book, Rights of Man.

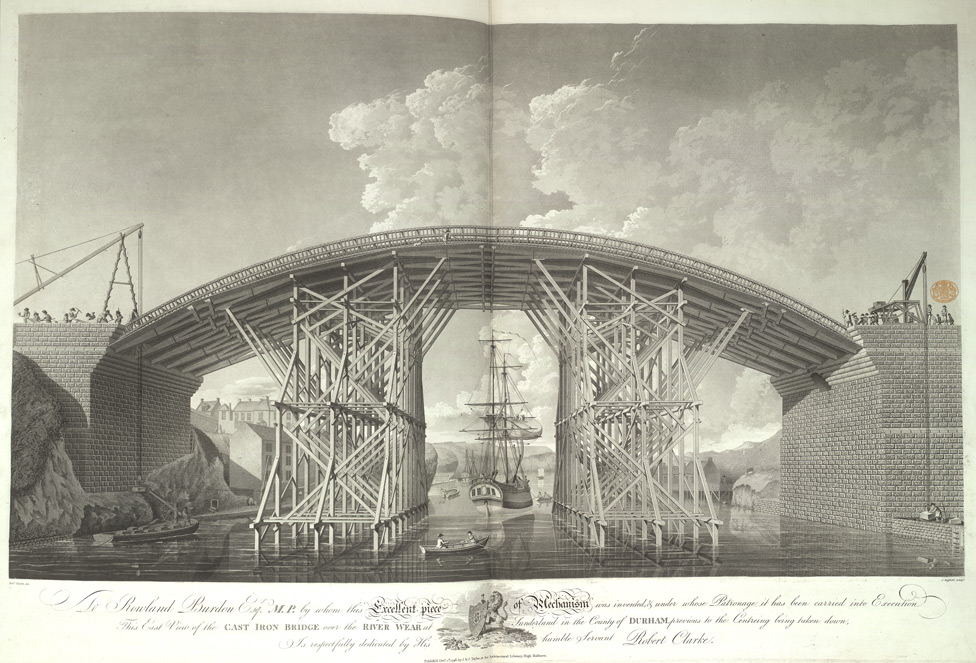

Meanwhile, says Sweeney, the London Model sat rusting in a field and had to be dismantled. Thomas Walker, who built the model, paid off debts by sending the iron north to construct his new bridge across the River Wear in Sunderland, a city in County Durham on the North Sea. Many of Paine’s cast components, likely supporting voussoirs, were used directly in the bridge. The rest of the iron was smelted and recast.

Walker constructed the Sunderland Bridge with Rowland Burdon, a local Member of Parliament. The bridge opened in 1796 as Britain’s second cast-iron bridge. Walker and Burdon took full credit for the Sunderland Bridge, but Paine is the one who really invented its design and technology.

Burdon took out his own patent in 1795, reports English historian John Morton in his Northeast Lore article, Durham’s other Member of Parliament, Ralph Milbanke, pleaded with Burdon to give Paine “compensation for the advantages the public may have derived from his ingenious model, from which certainly the outline of the bridge at Sunderland was taken.”

The Sunderland Bridge at 236 feet was twice as long as The Iron Bridge, becoming the world’s longest single-span bridge at 72 meters, writes Leonardo F. Troyano in Bridge Engineering: A Global Perspective. Paine never saw the Sunderland bridge in his lifetime, Troyano says, and he “did not get any credit for it,” but its appearance clearly was that of Paine’s design.

Morton quotes a Mr. Phipps, C.E., who wrote a report to 19th century architect Robert Stephenson:

We must not deny to Paine the credit of conceiving the construction of iron bridges of far larger span than had been made before his time, or of the important examples, both as models and large constructions, which he caused to be made and publicly exhibited.

Paine explicitly decided not to patent his bridge design in America, says Morton, but “he took care to put the country in possession of the means and of the right of making use of the construction freely.”

Paine wrote to Congress in 1803, “I have to request that this memoir may be put on the journals of Congress, as evidence hereafter that this new method of constructing bridges originated in America.”

Paine’s bridge is a metaphor for his life. With no formal education or training as an engineer, he joined a small number of people who contributed advances in technology to begin the Industrial Revolution. Like his political achievements were buried. Paine’s important role in the industrial revolution has been lost. It’s time for that to change.