Paul O’Dwyer – In Behalf Of An An Honest Man

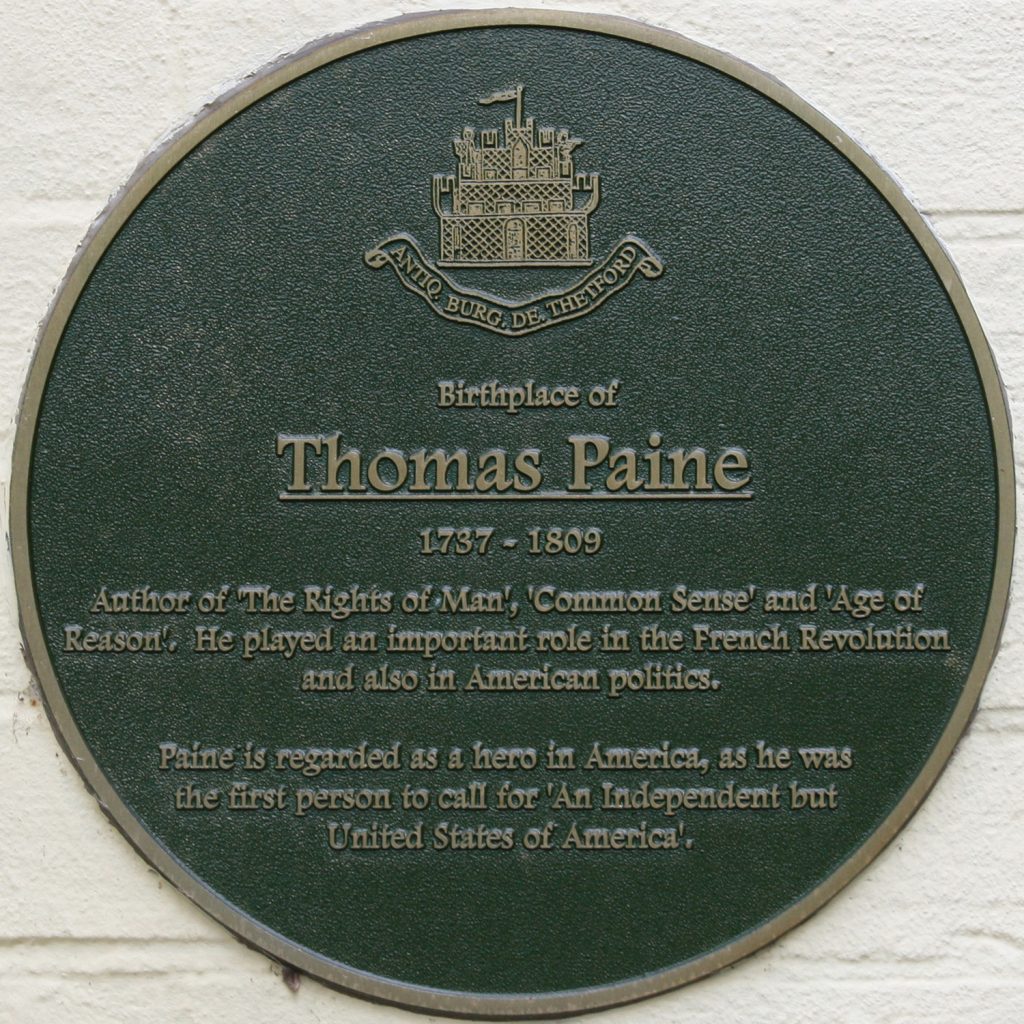

Many Americans are ambivalent about Thomas Paine, the 18th century British-American author and propagandist, for all kinds of reasons; he’s too radical in a modern way, perhaps. Paul O’Dwyer is not one of them.