By R.W. Morrell

Deptford’s Red Republican, George Julian Harney, 1817-1897. Terry Liddle. Pamphlet. 11pp. South London Republican Forum, 1997. £1.50

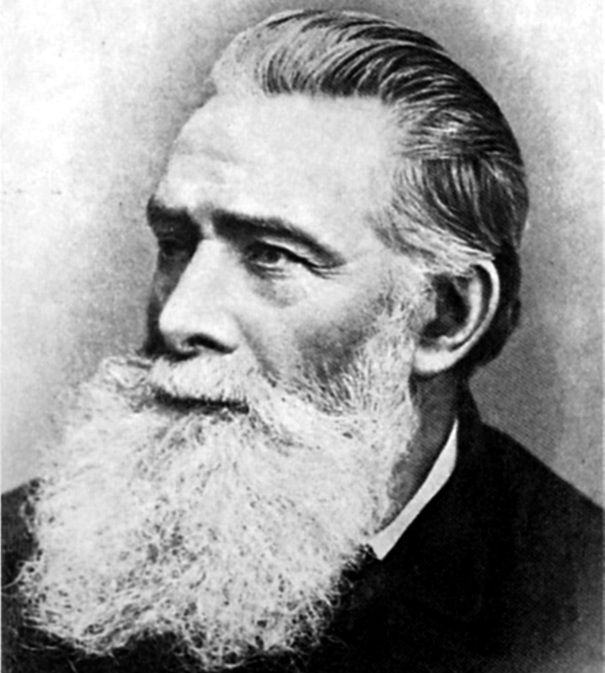

IN 1897 Dr.Edward Aveling interviewed Julian Harney, commenting about him: “I know that long after the rest of us are forgotten the name of George Julian Harney will be remembered with thankfulness and tears”. Terry Liddle cites this, noting that the words might not be bettered as his epitaph. Maybe, but it is an irony of history that Aveling’s name rather than Harney’s is now more likely to be remembered.

Although much of this publication is taken up with Harney’s Chartism and republicanism, the author does not neglect the many other political and secularist causes he became involved with. Among those few who have written on Harney there is general agreement that he was a brilliant writer, having, as Joseph McCabe says in his biography of Holyoake, a pen like that of Marat, although McCabe’s description of Harney as ‘a dark, moody little man…’ is historically incorrect. Chartism was very much part of his life and its demise in the 1850s might have left a void in the political life of many an individual, but not Harney. He rapidly increased and developed his contacts with the growing socialist and trade union movements, becoming a close friend of Frederick Engels and, for a time, Karl Marx, although the latter broke with him, having become increasingly annoyed by Harney’s refusal to censor articles critical of him in journals he edited. His friendship with Engels, however, continued, as did his respect for Marx.

As he became older Harney became more moderate in his approach to political matters, no longer being the political firebrand he once was. In fact the older he grew the more isolated he started to become, in some respects his situation resembled that of Paine in old age and he found it hard to make ends meet, nevertheless, like Paine he continued to write until the year of his death, one of his last pieces being some personal reminiscences he contributed to the Chicago based magazine, Open Court, in 1895 Terry Liddle is to be congratulated on having written a first-rate, if short, essay which brings to the fore an individual who, considering his importance, one would have expected to have attracted the attention of several biographers. Yet such is not the case. Indeed, as Liddle points out, there has been only a single full length biography, which he appears to have drawn heavily upon, A.R.Schoyen’s, The Chartist Challenge, A Portrait of George Julian Harney, published in 1958. This was originally a degree thesis and tends to read like one. Peter Cadogan has explored the relationship between Harney and Engels in an article published in the International Review of Social History (10. 1. 1965), and there have been some minor biographical studies such as `G. Mortimer’s”, ‘George Julian Harney, The Last of the Chartists’, which appeared in Free Review for March, 1896, the author of this is thought to have been J.M.Robertson. As might be expected Harney has also received some attention in academic papers, though for the most part the references are of a minor nature.

The impetus for this publication was the centenary of the death of Harney. The South London Republican Forum celebrated it, but requests to the Labour Party, the TUC and the Cooperative Movement to join it fell, as it were, on deaf ears. One might add here, that the Freethinker also ignored the centenary, despite the fact that Harney was a close friend of Charles Bradlaugh and G.J. Holyoake. The Freethought movement seems to be as neglectful of its pioneers as are the political and trade union establishments. If Liddle’s comments on the failure of the Labour Party, the TUC and the Cooperative Movement to commemorate the centenary of one of their own outstanding pioneers, prompts them to make amends, perhaps by funding a restoration of his memorial, which considering their collective financial assets would be chicken-feed, he will have achieved something of considerable significance, however, I hold out no great hopes as the leaders of New Labour (more accurately New Conservative) appear to be only interested in making political capital in order to retain power and the huge salaries and perks which go with it, hence the degrading spectacle of the leader of the party and his cronies boot-licking royalty.

This pamphlet makes a stimulating and informative read. Harney is known to have held Paine’s memory in high regard and may even have been one of the Chartists who influenced the movement to reprint and publish their own edition of Rights of Man. The failure to officially mark the centenary of his death also reflects the continual official failure to recognise events associated with Paine, as happened when Labour were previously in power. Liddle’s little work is at least a step in the right direction in that it seeks to make amends for the official silence. I would urge all readers to purchase a copy.