By Christopher Rumsey

Elizabeth, the wife of the famous (if not, infamous) revolutionary, Thomas Paine,a died in Cranbrook on 17 July, 1808, and lies buried in the churchyard of St. Dunstan’s. This fact is well known and is recorded by Tarbutt1 and also by Pile.2 The local newspaper for Cranbrook (the Maidstone Journal), contained the following announcement on 19 July, 1808.3

“Sunday morning, at her brother’s house at Cranbrook, in the 68thb year of her age, Mrs. Pain, wife of the notorious Mr. Thomas Paine, author of the Rights of Man, to whom she was married, at Lewes, in Sussex, in the year 1771.c She had lived only three years with this Assertor of Rights, when a separation took place, occasioned by his brutal behaviour to her, since which she has lived with her friends. She was the daughter of Mr. Ollive, a respectable tradesman in Lewes; she lived much respected, and died sincerely lamented – a firm Believer in Christ and the Truths of the Christian Religion – may his last days be like hers!’

It will be seen that the obituary is used as much to vilify Thomas Paine, as it is to lament Elizabeth’s passing. No doubt composed by her brother (in fact half-brother), Thomas Ollive, with whom she had lived in Cranbrook, the obituary reads like a cathartic rant, inveighing not only against Paine as an `assertor of rights’, but also by implication against his lack of Christian beliefs. A charitable interpretation of the final words of the obituary is that they refer to the example Elizabeth gave in her Christian readiness to embrace the life to come, rather than to any particular painful terminal illness that she had suffered. Clearly, it would have been possible for the obituary not to have made any reference to Paine himself. The implication must be that Elizabeth’s relationship to Paine was so well known that it would have seemed odd if it had not been mentioned. However, if it were to be mentioned, the treatment of Paine was to be one of censure. The fact was that, except in radical circles, Paine remained an anathema. Moreover, in this case the customary vituperation is heavily overlaid with personal animosity.

In essence, Paine’s notoriety derived from the impact of two works – Rights of Man4 (as referred to in the obituary) and The Age of Reason.5 The former, written as a rebuttal of Burke’s, Reflections…, appeared in two parts in 1791/2. It attacked the monarchy (`It requires some talents to be a common mechanic; but, to be a king, requires only the animal figure of man – a sort of breathing automaton.’); the aristocracy (`The idea of hereditary legislators is…as absurd as an hereditary mathematician, or an hereditary wise man.’); Burke’s love of tradition (`…as government is for the living, and not for the dead, it is the living only that has any right in it.’); and his disdain for the common people (`He pities the plumage, but forgets the dying bird.’). The book was an enormous success and in E.P. Thompson’s words was the ‘foundation-text of the English working-class movement.’ Paine became a household name, but also found himself the object of a major offensive from the Pitt government, which eventually led to his being convicted in absentia of seditious libel in December 1792. In The Age of Reason published in 1794/5 Paine posited a deist philosophy (I believe in one God and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life’) and attacked all organised religion in uncompromising language (All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolise power and profit.’). The book sold well and was to become the “bible” for nineteenth century freethinkers, but many (inaccurately) branded Paine as an atheist and he was generally reviled amongst those who attended church and chapel.

What of Paine’s alleged “brutal behaviour” to Elizabeth? What do we know of their relationship? The couple had first met in 1768 when he had come to Lewes to take up the position as an excise officer. He found lodgings in the Bull House at the top of the High Street, from which Samuel Ollive and his second wife, Esther, ran a retail snuff and tobacco business.6 There were four children – three by his first wife, Elizabeth (John, Samuel and Elizabeth) and one by Esther (Thomas).7 Paine seems to have been taken under his wing by Samuel Ollive and quickly became involved in local political and social circles, where he established himself as a formidable debater, as well as contributing articles for local publications. Samuel Ollive, however, died in July 1769 and, within a few months, Paine had accepted an invitation from Esther Ollive to help to run the Bull House business with her step-daughter, Elizabeth, “reportedly an intelligent and pretty woman,” some twelve years younger than Paine. Paine’s job as excise officer was not well paid – and he no doubt welcomed ‘moonlighting’ in the Ollive’s shop. The relationship between Elizabeth and Paine burgeoned and, having made their vows in Westgate Chapel,d they were duly married in March 1771 at St. Michael’s Church, Lewes (since the law did not permit marriages in dissenting chapels). Elizabeth’s eighteen year old brother, Thomas, was one of the witnesses.8

Without indulging in too much fanciful speculation, it is not difficult to see good reasons why Paine and Elizabeth were mutually attracted. For Elizabeth, Paine, who was somewhat older than her, may well have provided a father-substitute figure. She was no doubt impressed by the fact that her father had thought so highly of Paine that he had introduced him into influential civic and social circles in Lewes, where he had made a very favourable impact. Paine was tall and of an athletic build, with intense blue eyes, “full of fire, the eyes of an apostle.” Moreover, he possessed “innate charm and disposition” and an “easy conversational style”.9 Conway (who wrote the first authoritative biography of Paine) put it more succinctly: “He was her hero”.10 As regards Paine, we have already noted that Elizabeth was characterised by being both pretty and intelligent, with sufficient education, initiative and independence to have started a boarding school for young ladies in Lewes in January 1769.11 Moreover, the Ollive family provided a welcome refuge for Paine, who had been drifting somewhat aimlessly up to this point in his life, giving him an entree to local circles in Lewes and a level of social respectability.

However, as Keane12 reports, within a year of their marriage, an “icy quarrel” broke out between Elizabeth and Paine. “Paine was absent for several months in London campaigning on behalf of the Excise officers… Rumours spread that the newlyweds had never slept together… Others said that a local doctor, John Chambers, had quizzed Paine ‘on the non-performance of the connubial rights’ and that Paine’s impotence had led him to fling himself into the Headstrong Club,e town affairs, his work and the campaign to build a union for excise men. Still others whispered that Paine was too set in his ways, neglectful of his wife and business, and too bent on drinking and arguing ‘politick affairs’. Unaware of the death in childbirth of his first wife, no one considered whether Paine, driven by guilt and shame, had subsequently developed a coldness toward women and a liking for men’s company.” Regarding the charge of impotence, Fruchtman13 cites a comment from Clio Rickman, a long-time friend and biographer of Paine, who had asserted that “no physical defect on the part of Mr. Paine can be adduced as a reason for such conduct”.14 Interestingly, Conway15 cites Paine’s increasing deviant religious views as being the real basis for the developing schism with Elizabeth.

Things went from bad to worse. In April 1774 Paine was dismissed from his position as an excisemen for spending too much time away from his post and incurring debts. In the same month, all his personal effects were auctioned – an indication of his public bankruptcy. Elizabeth and Paine separated soon afterwards. The relevant articles of separation record simply that: “Dissensions had arisen between the said Thos. Pain and Elizabeth, his wife, and that they had agreed to live separate.” Paine was always tight-lipped about the underlying reason for their alienation: “it is nobody’s business but my own, I had cause for it, but I will name it to no one.” In the case of Elizabeth the separation may have been more understandable – a husband who probably offered her little affection, who spent long periods away from the marital home, who was an inadequate bread-winner, yet who would indulge in high-flown rhetoric about “justice for the poor and more liberty for all”. Thomas and Elizabeth finally parted in June and were never to see or communicate (as such) with each other again.16 According to Rickman, “Mr. Paine always spoke tenderly and respectfully of his wife” and periodically sent her money anonymously.17

Keane18 reports that Elizabeth was disgraced by the separation and was thus compelled to leave Lewes with few possessions and never returned there. He also states that she came to Cranbrook to live with her brother, Thomas Ollive, a clock-maker. There is in fact no definite information as to when Elizabeth came to live in Cranbrook. We can contrast Keane’s account – of her need to leave Lewes in something of a hurry – with Newton Taylor’s speculation that Elizabeth may have come to Cranbrook in 1789 with her step-mother, Esther Ollive, to look after Thomas Ollive’s three young daughters following the death of their mother.19 We do know that Thomas had become a master clock- maker in 1777 and in February of that year is listed in the Churchwardens’ Rate Books as occupying a property next to the George Inn on the church side of that property. He remained there until 1791, at which time he moved to a property on the north side of Stone Street (formerly the Freeman Hardy & Willis shop, now Berry Antiques). It is thought that he remained here until his death in 1829.20

Whatever year Elizabeth came to Cranbrook, it is clear that as a separated woman she would have derived her standing and status in Cranbrook society from Thomas Ollive. The only direct reference that I can find regarding Elizabeth’s life in Cranbrook can be found in Vale’s, The Life of Thomas Paine, published in 1841.21 It is worth quoting in full: “She was afterwards a professor of a sectarian religion in Cranbrook, Kent, and boarded in the house of the watchmaker, a member of the same church; his house was consequently visited by religious people, many of them with strong prejudices and some very ignorant. These, after the publication of The Age of Reason, would sometimes speak disrespectfully of Mr. Paine in her presence, when she wilfully left the room without a word. If, too, she was questioned on the subject of their separation, she did the same. We have these facts from those who resided with her. Our most intimate friend at one point was a Mr. Bourne, a watchmaker in Rye, about eighteen miles from Cranbrook, England. This gentleman was apprenticed in the house where Mrs. Paine lived; he sat at the same table with her for years. We have these facts confirmed by other residents of Cranbrook. Thus nothing could be learned from her, except that though she differed from Mr. Paine on religious subjects, she could not bear to hear him spoken ill of.”

Vale’s reference to “a sectarian religion” ties up with what we have been able to establish about Thomas Ollive. We know that in 1793 he was one of the signatories to an application for a certificate under the Toleration Act of 1689 to form a dissenting congregation at Isaac Beeman’s premises in Cranbrook (which were later to form the site for Providence Chapel.22 It is therefore not un-reasonable to suppose that Thomas and Elizabeth were members of the congregation there. There is a certain irony about this, as Huntington, who preached periodically in Cranbrook, and who in Wright’s words23 was ‘a high Tory and a perfervid admirer of Pitt’, viewed Paine as the devil incarnate. For example, in December 1797 in a sermon entitled ‘Watchword and Warning’ he urged his congregation in London “to obey the voice of God” rather than give heed to “the claims of Popery, the teachings of Tom Paine, and the tyranny of the mob.” It is not unreasonable to suppose that Beeman’s message to his congregation was a similar one. If it were so, then Elizabeth would surely have been discomforted by hearing it.

Whilst it appears that the fact that Elizabeth was the wife of Thomas Paine was not hidden from Cranbrook residents, there seem to be grounds for thinking that she was a potential victim of persecution. For example, the Sussex Weekly Advertiser (published in Lewes) noted in its 8 July, 1793 edition:24 “It is not true that Tom Paine’s wife subsists on the bounty of her neighbouring parishes, as stated in a Morning Paper on Saturday. She is a native of this town, and now follows the business of a mantua-maker,f near London, by which she gets a good livelihood, independent of what she receives from her relations, who we believe are very kind to her.” It seems clear that the Ollives still had good friends in Lewes (and it is known that Thomas her brother maintained links with it). The certain coyness about Elizabeth’s whereabouts and her alleged proximity to London does not detract from the fact that she probably resided in Cranbrook at this time.

Following the publication of Rights of Man, Paine became a major target for the ‘counter-revolution’ of the Pitt government. One of its ploys was to circulate a copy of a letter supposedly written by Paine’s mother, Francis, to Elizabeth on 27 July, 1774, following her separation from Paine.25 The letter lambasts Paine for being both a worthless son and husband. Some doubts exist as to the authenticity of this document, but it really is pretty mild stuff with which to sully an opponent. If the letter is authentic the obvious provider would be the original recipient of the letter, Elizabeth herself. However, it seems apparent that she still felt a lingering affection for Paine, so she is unlikely to have colluded in besmirching his reputation. The whole matter remains a mystery.

In 1800 Elizabeth’s step-mother, Esther, died in Cranbrook. In that year – no doubt associated with the latter;s demise – Elizabeth was party to a property agreement which states that: “the said Elizabeth Pain had ever since lived separate from the said Thos. Pain, and never had any issue, and the said Thomas Pain had many years quitted this Kingdom and resided (if living) in parts beyond the seas, but had not since been heard of by the said Elizabeth Pain, nor was it known for certain whether he was living or dead”.26 According to Williamson,27 the seals attached to the signatures of the parties to the agreement show the head of Thomas Paine as a young man – a further indication of Elizabeth’s endearment. However, the statement itself shows a complete distancing of Elizabeth from Paine himself. Surely, she was not so isolated in rural Cranbrook that she had not been aware of the fame and infamy that had greeted both parts of Paine’s hugely successful Rights o/ Man in 1791/2 and The Age of Reason in 1794/5. In fact we know from Vale’s account28 that this was certainly not the case regarding the latter. More likely she regarded the statement as merely legalese that she was only too pleased to sign in order to tidy up some legal loose ends.

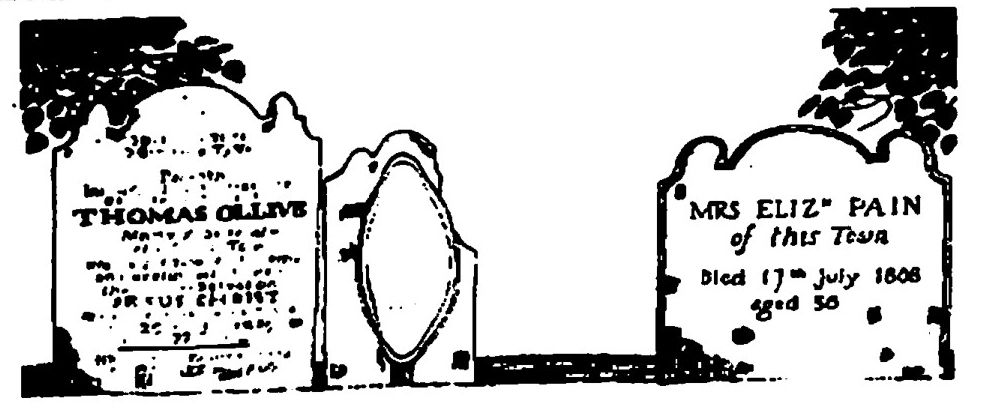

Elizabeth died in July 1808 and, as we have noted, her death was announced in the Maidstone Journal Also, according to Williamson, in another newspaper (which I have so far been unable to trace). The latter notice apparently reflected her wishes by stating that to abuse her husband would be “needless, ungenerous and unjustifiable”.29 Thus, according to this account, Elizabeth would seem to have retained a deep affection for Paine. If Williamson’s account is correct, then it shows that Elizabeth’s view of her husband contrasted sharply with that of her brother, Thomas, who was almost certainly the author of the vituperative Maidstone Journal obituary quoted earlier. Indeed, there seem to be grounds for believing that their differences over Paine gave rise to a degree of antipathy between them. Illustratively, the place where Elizabeth was buried in Cranbrook churchyard is not where her gravestone currently stands – adjacent to that of her brother Thomas Ollive, and presumably that of another member of the Ollive family (which is completely impossible to decipher). We know this from a hand-written reference in the museum archives, which states: “the tombstone of the grave of Miss Ollive – wife of Tom Paine, has been moved to a position close to other memorials of the Ollive family`.30 Moreover, Elizabeth’s headstone carries a very simple, if not, stark inscription: “MRS ELIZH PAIN of this Town Died 17th July 1808 Aged 58”. While it was not to be expected that reference should have been made to her husband, it is perhaps unusual for some form of endearment not to have been added, nor anything about the hereinafter. Contrast this inscription, for example, with that of her brother which almost smugly speaks of, inter alia, “a life of exemplary piety and usefulness wholly relying on the full and free salvation of JESUS CHRIST”.31

In conclusion, it seems likely that when Thomas Paine became a household name in the 1790s, Elizabeth not only publicly acknowledged that she was his estranged wife, but even implicitly defended his personal reputation. On the other hand, her brother Thomas – as a prominent local tradesman, and probable Pitt supporter, with declared Christian beliefs – must have preferred that Paine did not intrude into his life in Cranbrook and that ‘Miss Ollive’ lived a secluded rural existence. Following the publication of The Age of Reason in 1794/5, Thomas like others must have come to regard Paine as a complete infidel – and already as someone whom he regarded as having ruined his sister’s life and embarrassed his own. When Elizabeth died in 1808, the obituary that he drafted gave vent to his accumulated venom regarding Paine.

References and Notes

a. From at least 1774, Thomas Paine added a final ‘e’ to his name and this spelling is used throughout when referring to him, except where direct quotations spell the name otherwise.

b. This is incorrect. Elizabeth was born in December 1749. She was therefore in her 59th year at the time of her death.

c. Her marriage to Paine in fact took place in 1771.

d. John 011ive, Samuel’s father, had been minister of this chapel (which was Calvinistic in learning) between 1711-40.

e. An all-male dining and debating club which met at the White Hart in Lewes High Street.

f. i.e. a dress-maker.

1. Tarbutt, W. Second Lecture The Annals of Cranbrook Church, (1873). p.45.

2. Pile, C.C.R. Cranbrook: A Wealden Town. (1990). pp.75-76.

3. Maidstone Journal, 19 July, 1808. For a more temperate obituary please refer to that in Sussex Advertiser, 25 July, 1808.

4. Paine, T. Rights of Man with introduction by E. Foner. 1984. pp.174, 83, 45 and 51.

5. Paine, T. The Age of Reason, Part 1. in, The Thomas Paine Reader, edited by M. Foot & I. Krammick. (1987). p.400.

6. Keane, J. Tom Paine – A Political Life. (1995). p.62.

7. Newton Taylor, P.S. ‘Many Years an Inhabitant of this Town’. Cranbrook Journal, No.6. (1993). p.10.

8. Keane. op. cit. pp.65-71& 75-76.

9. Fruchtman, J. Thomas Paine – Apostle of Freedom (1994). op.26 & 38.

10. Conway, M.D. The Life of Thomas Paine. (1892). Volt p.26.

11. Sussex Weekly Advertiser. 30 January, 1769.

12. Keane. op.cit. p.77.

13. Fruchtman. op. cit. p.36.

14. Rickman, T.C. The Life of Thomas Paine. (1819). p.15.

15. Conway. op. cit. pp.31-32.

16. Keane. op.cit. p.78.

17. Rickman. op. cit. p.45.

18. Keane. op.cit. p.78.

19. Newton Taylor. op. oil. p.11.

20. Newton Taylor. Ibid. p.11.

21. Vale, G. The Life of Thomas Paine. (1841). p.25.

22. CKS QISB 264. (1793).

23. Wright, T. The Life of William Huntington S.S. (1909). p.108.

24. Sussex Weekly Advertiser, 8 July, 1793.

25. Paine, F. to ‘Dear Daughter’, Thetford, 27 July, 1774.47.6.12.105 British Museum (reference in Keane. op.cit. p.595).

26. Williamson, A. Thomas Paine: His Life, Work and “limes. (1973). p.57.

27. ibid. p.57.

28. Ref.21 above.

29. Williamson. op.cit. p.53.

30. Cranbrook Museum Archives, Ref.1397, ‘Grandfather Clock 1752-1829’, p.4.

31. I am most grateful to Mr. P.S. Newton Taylor for supplying this and other information relating to the Ollive family.

This article was first published in the Cranbrook Journal by the Cranbrook and District Local History Society in 1997.