By R.W. Morrell

Edmund Frow (Eddie) 1906-1997, THE MAKING OF AN ACTIVIST. Ruth Frow. Illustrated. 168pp. Paperback. ISBN 0 9523410 9 3. Salford, Working Class Movement Library, 1999.

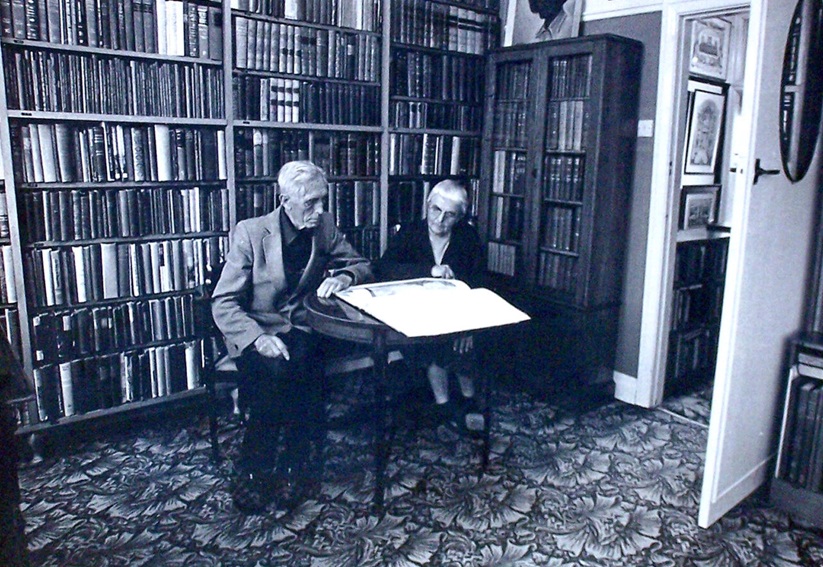

ANYONE seriously interested in radical working class history owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Eddie Frow (and Ruth Frow), for having brought into being the Working Class Movement Library. When so many were oblivious to the rich history of the British working class as illustrated through its literature, they commenced to assiduously seek these publications, and manuscript material, out which eventually grew to enormous proportions. Thankfully they did not sell their collection, for over the past twenty or so years institutional interest in ‘social history has increased dramatically and many collections and individual rare books and pamphlets have emigrated from these shores to collections, public and private in the United States, and, one might add, to Japan. Instead they took steps to preserve their collection, and made it available to all with a serious interest in working class history. It was very much to the credit of Salford Council that they offered a home to the collection, which is still being added to.

This is not a biography in the strict sense of the term, but rather, as she describes it, an anecdotal biography. From its pages its subject emerges as a remarkable and certainly brave individual dedicated to the welfare of his fellow men, although there are times when the reader who does not share his political ideology gets the impression that he may have achieved greater results had he displayed a greater degree of political flexibility, which could have been done without compromising his beliefs. This point is made by another former trade union leader, Bob Wright, when he refers to his ‘dogmatic tendency’ and goes on to identify what he considers to be his colleague’s `blind spots’, which he describes as a `reflection of his Communist Party discipline or a Marxist analogy’ which tended to make him ignore the practical problems of trade union life in a non-socialist/aggressive capitalist situation. Nevertheless, Wright stresses that Eddie was ‘a kind man with a moral discipline, though not one happy with having a drink in the local pub, preferring, instead, to ‘go home and read’.

Eddie (and Ruth) Frow’s passion for books comes increasingly to the fore in this work when the author discusses the origins and ultimate fate of their magnificent library. How they travelled around on holidays and at weekends to rummage in secondhand bookshops, giving details, in brief, of some of their finds and how they managed to attract donations of collections to enhance the library, which had been made into a trust the experiences related strike a chord in me as I have a passion for secondhand bookshops and well know the feelings when chancing upon a particularly desirable book at a price I could afford. Both Ruth and Eddie Frow were members of the Thomas Paine Society (I am unsure whether Ruth remains one), and it was to their Working Class Movement Library that the late Christopher Brunel, a good friend of the Frows and first Chairman of the TPS, left his superb Paine library, perhaps the finest Paine collection in Britain, thus making the library one of the most important places where rare works by and on Thomas Paine and his influence can be consulted – I had been under the impression, from what he had told me, that it was to go to the Marx Memorial Library in London, with which Chris had close associations.

Formal recognition of the Frow’s work was given when they were awarded Honorary Degrees by Salford University and Edmund made an Honorary Fellow of Manchester Polytechnic. In addition they were elected as Honorary Fellows of the University of Mid-Lancashire the Library Association gave them a Special Certificate of Merit. A fact not mentioned in the book is the award of a substantial grant to the Working Class Movement Library by the National Lottery to pay for the rebinding of scarce books. Although he may not have approved of the Lottery, I suspect Edmund Frow would have approved of the grant.

On a personal level I have good reason to remember Edmund Frow with gratitude, for when researching a particular obscure individual for a – paper I had been requested to write, I had come up with a complete blank. In desperation I wrote to him and a few days later received several pages of photocopied material which not only supplied some of the facts I required but also pointed me in the direction of where I could find additional information. Perhaps I am biased, although I hope not, but I found this an absorbingly interesting book, one of the few which I literally read in one session. Its subject comes alive in its pages, for Ruth Frow is an extremely able writer, and one does not have to share his (and her) political beliefs to enjoy it. It is also an important record of political and trade union activity, primarily in the Manchester area, where Edmund Frow achieved one of his major desires, election as a full time union official, although he was not in the job long enough to receive a union pension when he retired.

The book is well illustrated and if I have any criticisms, they are of a selfish desire to want to know more about the books and book collecting exploits of Eddie and his wife, which could well, I suspect, make a book in themselves. One final critical point, although mention is made of ‘the Thomas Paine Collection’ being willed to the library there is no reference to the person who willed it, Chris Brunel, the first chairman of the TPS.