By Lewis H. Lapham

“Remarks on Thomas Paine” at Iona College in New Rochelle, October 19, 2012 [an edited transcript excerpt]

On being asked ten years ago to speak to the Thomas Paine National Historical Association here in New Rochelle, I assumed that it would be a simple matter of stringing together the literary equivalent of a laurel wreath and setting it upon the head of a statue. It had been several years since I’d read The Age of Reason or Rights of Man, but in my own writing I’d borrowed more than one of Paine’s lines of argument, often unwittingly, nearly always to good effect, and I didn’t think I’d have much trouble placing the figure of Paine on the pedestal of the heroic American past.

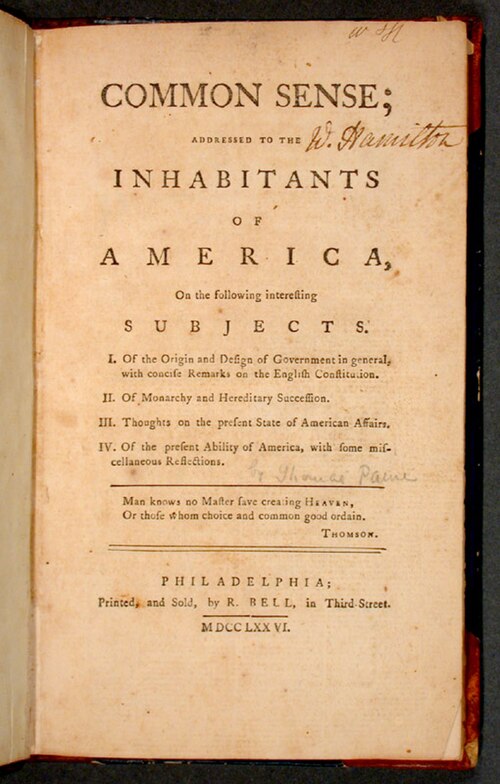

Before appearing on the lectern I fortunately took the precaution of re-reading Common Sense, and instead of finding myself in the presence of a marble portrait bust I met a man still living in what he knew to be “the undisguised language of historical truth,” leveling a fierce polemic against a corrupt monarchy that with no more than a few changes of name and title, could as easily serve as an indictment of the complacent oligarchy currently parading around Washington in the costumes of a democratic republic.

Invariably in favor of a new beginning and a better deal, Paine was speaking to his hope for the rescue of mankind in a voice that hasn’t been heard in American politics for the last forty years, and the old words brought with them the sound of water in a desert:

When it shall be said in any country in the world, ‘My poor are happy; neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them; my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars; the aged are not in want; the taxes are not oppressive…’ when these things can be said, then may that country boast its constitution and its government.

Why is it that scarcely any are executed but the poor?

The abundance of Paine’s writing flows from his affectionate and generous spirit. During the twenty years of his engagement in both the American and French revolutions, he counts himself “a friend of the world’s happiness,” believing that the strength of government and the happiness of the governed is the freedom of the common people to mutually and naturally support one another.

Republican democracy he conceived as a shared work of the imagination among people of disparate interests, talents and generations, and therefore as the holding of one’s fellow citizens in thoughtful regard, not because they are beautiful or rich or famous, but because they are one’s fellow citizens…..

The force of Paine’s writing is of a match with his purpose, which is to empower his readers with the confidence to know the value of their own minds. He frames his thoughts in language plain enough to be understood by everybody in the room, his remarks addressed not only to the learned lawyer and the merchant prince but also to the ship chandler, the master mechanic and the ale-wife. Paine’s writing is revolutionary because it is a democratic means to a democratic end….

Unlike the political theorists employed by our own self-important news media, Paine doesn’t think it the duty of the political writer to keep things running quietly and smoothly. His aim is to arm ordinary individuals with the weapon with which to defend themselves against organized deception and arbitrary power. The intention is explicit in the composition of Common Sense, which is why it excited so welcome a response among readers everywhere in the colonies when it was published in January 1776.

Lewis Henry Lapham edited Harper’s Magazine from 1976 to 1981, and 1983 to 2006. He founded Lapham’s Quarterly to focus on history and literature.