by Joy Masoff

Part One of a Three-Part Historiography

Even before Paine’s death, his life was being dissected by those around him on both sides of the Atlantic. The earliest “biographies” of Paine were highly critical, politically-motivated smear campaigns funded by political enemies in high places. Each writer set out to debunk Paine’s major works, especially Common Sense; The Crisis; and the Rights of Man.

The earliest published works were political hatchet jobs by Paine’s enemies. Francis Oldys, a 1793 biographer, really was George Chalmers, masquerading as a University of Pennsylvania divinity professor. Chalmers painted Paine as a drunken, lazy wife-beater.

William Cobbett, another British expatriate in America, joined Chalmers in verbally tarring and feathering Paine. Cobbett’s The Life of Thomas Paine (1797) built upon the foundation of Chalmers’ work and quoted heavily from it.

Like Chalmers, Cobbett offered a running editorial commentary about Paine’s embrace of enlightenment thinking and then picked up with Paine’s life through his release from prison during the French Revolution. Cobbett wrote:

Whenever or wherever he breathes his last, he will excite neither sorrow nor compassion… men will learn to express all that is base, malignant, treacherous, unnatural, and blasphemous, by a single monosyllable, Paine.

This statement demands a word about the long and erratic relationship between Cobbett and Paine, the downs and ups of their often parallel lives.

Both were sons of the British working class. Both were successful pamphleteers, although Paine was more commercially successful. Both suffered some degree of egotism and arrogance.

Cobbett, the angry polemicist, later made a drastic emotional U-turn and disinterred Paine’s corpse from its New Rochelle resting place for an envisioned monument to honour Paine in England, where it was not permitted.

The Cheetham Biography

Shortly after Paine died in 1809, his enemies and friends began sharpening their quills. Some spewed vitriol, while others offered praise.

James Cheetham, the New York publisher of a newspaper called The Citizen, was a colleague of Paine turned bitter foe. Cheetham’s The Life of Thomas Paine (1809) opened with a description of his first meeting with Paine in New York in 1802, shortly after Paine returned to the United States from France. A more unsavory description of the encounter cannot be imagined, which is interesting because Cheetham published Paine’s writing in The Citizen for five years until a falling out (evidently over pay) led to Paine’s refusal to write for him anymore.

Claiming impartiality, Cheetham wrote that his goal was “neither to please or displease any political party. I have written the life of Mr. Paine, not his panegyrick [sic].” Rather than telling the life of Thomas Paine, Cheetham brought an indictment.

Cheetham said he’d interviewed many who knew Paine personally, describing them as people of the highest echelons of society. He ridiculed/ Common Sense as “Defective in arrangement, inelegant in diction…” While ostensibly analyzing all of Paine’s writings, Cheetham relentlessly criticized them.

So vituperative is Cheetham’s tone that one wonders if there’s any value in reading it, but it captures the ethos of the Painehaters, giving a better understanding of the constant bile Paine faced throughout his life in the public eye.

Harford, Rickman, Sherwin, and Carlile

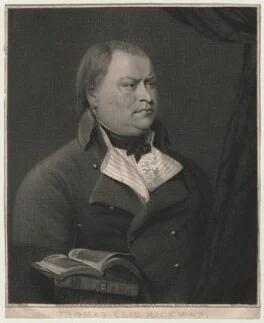

Ten years after Paine’s death, a quartet of biographies appeared within months of each other: John S. Harford’s Some Account of the Life, Death, and Principles of Thomas Paine (1819); Thomas Clio Rickman’s The Life of Thomas Paine (1819); W. T. Sherwin’s Memoirs of the Life of Thomas Paine (1819); and Richard Carlile’s The Life of Thomas Paine (1820).

Harford picked up where Cheetham left off, offering a scathing portrait of a despicable human being. The other three mounted a defense against the virulent misrepresentations of Paine’s life. Rickman, Sherwin and Carlile actually knew Paine and believed that fear of progressive ideas, not facts, were behind the grotesque portrayals being offered.

John Harford came from a wealthy British banking family. While he shared Paine’s abolitionist sentiments and began his biography promising to be less vindictive than Cheetham, he unleashed an equally critical diatribe. While conceding that Paine did have “considerable natural talent, ” Harford presented Paine as cruel, unclean, constantly drunk, and miserly. He painted Paine as being possessed of an “inordinate spirit of egotism and selfishness which rendered him incapable of friendship to a single human being.” He described those who befriended Paine as “chiefly low and disreputable persons.”

stipple engraving, published February 1800 – © National Portrait Gallery, London

Clio Rickman, a lifelong friend of Paine, set out to rescue his friend “from the undeserved reproach… cast upon it by the panders of political infamy.” Rickman knew Paine better than anyone and had much in common with him. He grew up in Lewes, the coastal Sussex town where Paine lived, worked and became politically active between 1768 and 1774. The two men shared Quaker beliefs and a love of books. Rickman eventually moved to London, became a publisher of political pamphlets, and a lifelong friend.

William Thomas Sherwin, a London publisher, wrote the first unbiased assessment of Paine’s life. For Memoirs of the Life of Thomas Paine, Sherwin interviewed Paine’s personal and political friends to offer a biography devoid of mudslinging and name-calling.

Sherwin pointed at Chalmers, who was paid £500 to smear Paine’s reputation. He pilloried Cheetham as a “treacherous apostate” and “illiterate blockhead.”

One year later Richard Carlile, released The Life of Thomas Paine. Carlile also rebutted Cheetham’s work by presenting an entirely laudatory portrait, built upon the same structure of analyzing each work in counterpoint to Paine’s life at the time of its writing.

Carlile’s Paine is a man above reproach, a man so honest that he would not let a friend correct one of his grammatical errors, saying, “he only wished to be known as what he really was, without being decked with the plumes of another.”

Vale and Linton

These early works cannot be read as traditional biographies, but they prove useful as a way to understand Anglo-American radicalism in the eighteenth-century. Cobbett, Harford, Rickman, and Carlile all lived with one foot in America and the other in Britain. Much like Paine they were “ideological immigrants.”

A Compendium of the Life of Thomas Paine (1837) by Gilbert Vale was the first biographical study intended to look at Paine through an American lens, untinged by Whig versus Tory politics. Vale was London-born, but he openly tried to remove Paine’s story from friends and foes on European shores.

Vale wrote from avowed neutrality, determined to neither debase nor laud. He declared, “We are not… about to write a eulogy; to enhance his virtues, or to suppress his faults, or vices. Paine was a part of human nature, and partook of its imperfections.”

William James Linton’s The Life of Thomas Paine (1841) clearly shows where his sympathies lay. Linton called Paine a “sturdy champion of political and religious liberty.” In subsequent editions, Linton wove in brief profiles with homage quotes from some of Paine’s notable cohorts — such as Benjamin Franklin and Mary Wollstonecraft — to further humanize him.

By the mid-1800s, Paine had become a man instead of a monster. The dawn of the 20th century would bring a new scrutiny to his life.