By Terry Liddle

Bradlaugh Contra Marx, Radicalism And Socialism In The First International. Deborah Lavin. 86pp. Paperback. London, Socialist History Society, 2011. ISBN 9 7809555 13848. £4.00.

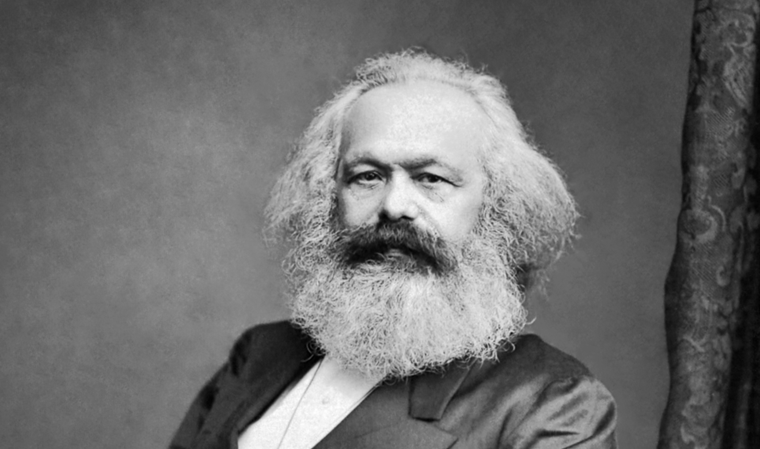

This is a fascinating glimpse into socialist and radical politics in the mid-nineteenth century. On the one hand there is Karl Marx, a Communist and political exile in London, on the other Charles Bradlaugh, who rose from humble origins to become the leading nineteenth century advocate of Secularism and a MP for Northampton. Both were political giants. In his day Bradlaugh was far better known than Marx, although while the National Secular Society, which Bradlaugh founded in 1866 is still going there is nothing of his prolific writings in print.* Although the cheap editions of Marx’s works produced in Moscow are no longer being printed, his work is still being published and in the light of the current economic crisis, his theories hotly debated.

The First International, albeit short-lived – it lasted less than a decade, was the first attempt by the working class to organise on an international scale. Marx joined almost by accident, being invited to join as a delegate from Germany by Victor Le Lubez, a French exile and close friend of Bradlaugh, who was an active Secularist both in Greenwich and nationally. Marx quickly became a leading figure in the International.

Ms. Lavin is an undoubted protagonist of Marx and seeks to undermine Bradlaugh as an heroic figure, indeed she rather over eggs the pudding and at times comes near to character assassination if not defamation. She shows that Bradlaugh’s role in the trial of himself and Annie Besant under the Obscene Publications Act for publishing and distributing the birth control pamphlet The Fruits of Philosophy was far less heroic than has been depicted. Besant was related to the Liberal Lord Chancellor, Lord Hatherley, and Ms. Lavin alleges that he used his influence to ensure that Besant and Bradlaugh were not imprisoned. On the other hand, Edward Truelove, a former Chartist and the International’s printer, got four months for distributing the pamphlet.

Ms. Lavin decries Bradlaugh and Besant’s Neo-Malthusianism which was the sole cause of working class poverty as their prolongation in their reproduction. She accuses Besant of giving incorrect information in her birth control pamphlet, The Population Question. She does not mention Dan Chatterton who while working with the rather puritanical Maithusian League, advocated sex for pleasure.

Ms. Lavin describes Bradlaugh’s role in the struggle over the oaths question, he wanted to affirm his loyalty to Queen Victoria, her heirs and successors rather than swear a religious oath, as more accidentally than deliberately heroic. Bradlaugh was a leading republican, but Ms. Lavin does not address the conflict between Bradlaugh and John De Morgan, a former member of the Cork branch of the International, in the republican movement of the 1870s.

She writes that Marx’s daughter Laura says that he went to hear Bradlaugh speak in the 1850s and seeing him as a muddleheaded radical possibly capable of reform. In any event, Marx did his utmost to keep professional atheists out of the International, in particular the Holyoake brothers who were opponents of Bradlaugh. Here I think he was wrong, George Holyoake was a pioneer co-operator, when he died nearly four-hundred co- operative societies subscribed to erect a building in his memory. He could have brought many co-operators and Secularists into the International.

Bradlaugh was a leading member of the Reform League which had been formed in 1866 to advocate the extension of the franchise to more working class men. It staged some of the most militant demonstrations since Chartist times which Ms Lavin compares to the anti-poll tax demonstrations of the 1990s and more recent student demonstrations against rises in tuition fees. During one, demonstrators tore down the railings in Hyde Park and used them to defend themselves from police baton charges. She shows that the leaders of the League were bought by the Liberals to mobilise newly franchised workers behind Gladstone and keep independent working class candidates out of the contest. Although initially opposed by the Liberals, Bradlaugh eventually became an official Liberal Party candidate.

The first International was wrought with conflict between Marx’s communism, English trade unionists who in essence remained Liberals, followers of the French anarchist Proudhon and supporters of the Russian anarchist Bakunin. All of these came together to support the Paris Commune of 1871, which was drowned in blood by the forces of reaction. Although Bradlaugh was a Freemason and the French masons supported the commune, he opposed it. This led to a fierce clash between him and Bradlaugh in the pages of the Eastern Post.

The International, however, was in a bad way and by 1872 it was in effect dead. At its Hague conference its general council was moved from London to New York. Bradlaugh now tried to form his own international. From 1877 this was muted in his weekly National Reformer. He had wanted to call the new body The International Workingman’s Association, the original name of the International, but it was decided to call it the International Labour Union. Among its supporters were the Rev. S. Headlam and the anti-socialist trade unionist Edith Simcox, one of the first female delegates to the Trades Union Congress. The ILU began to slip out of Bradlaugh’s control. It supported the cotton workers’ strike against a pay cut and when George Howell attacked Marx, Harriet Law, who had been involved in the original International, offered Marx space to reply in her Secular Chronicle. After that the ILU faded out of existence.

Marx died in 1883 and the following year Henry Hyndman formed the Democratic Federation. He debated with Bradlaugh and while many seem to think Bradlaugh won, but within months two of the triumvirate which led the NSS, Annie Besant and Edward Aveling, had become socialists.

Ms. Lavin has long been working on a biography of Aveling and if it is as good as this work is it will be well worth the wait.