By R.W. Morrell

Contested Sites, Commemoration, Memorial and Popular Politics in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Paul A. Pickering and Alex Tyrrell. 192pp. Illustrated. Hardbound. Ashgate, 2004. ISBN 0 7546 3229 6. £45.00

Britain’s towns and cities are littered with memorials to those we are supposed to consider as the great and the good. Whether most of those they commemorate can really be described as great is debatable, while the designation as good is highly subjective. Amongst this mass of monuments are to be found a handful dedicated to radicals and reformers, many of whom suffered appallingly at the hands of the aforesaid ‘great and good”. The accounts as to how these radical monuments came to be erected, or not erected, can be quite fascinating as the essays in this book show.

Contested Sites consists of seven essays compiled by Pickering and Tyrrell along with Michael David, Nicholas Mansfield and James Walvin, their titles being, ‘Bearding the Tories: The Commemoration of the Scottish Political Martyrs of 1793-94’; ‘A Grand Ossification: William Cobbett and the Commemoration of Tom Paine’; Radical Banners as Sites of Memory: The National Banner Survey’; ‘The Chartist Rites of Passage: Commemorating Feargus O’Connor’; Preserving the Glory for Preston: The Campo Santo of the Preston Teetotallers’, and, ‘Whose History Is It? Memorialising Britain’s Involvement in Slavery’. An opening chapter, ‘The Public Memorial of Reform: Commemoration and Contestation’, presents an overview of the book’s theme.

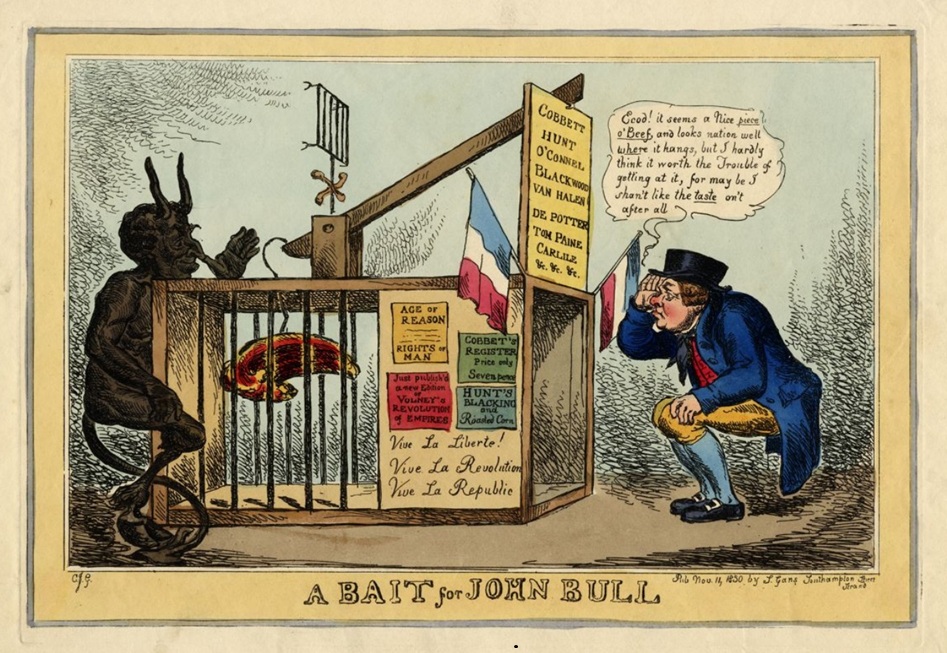

Perhaps the chapter which will probably first attract those interested in Thomas Paine is that by Paul A. Pickering which presents an account of a failure by William Cobbett to carry through a plan to have a major monument erected in England commemorating Paine, which was his excuse for exhuming his remains. Pickering’s detailed analysis of what occurred after the remains arrived in England and Cobbett’s efforts to carry out his aim makes for absorbing reading. The author draws attention to Cobbett’s hostility to many of Paine’s ideas, notably his republicanism and views on religion, nor can the suspicion be escaped that he also used Paine’s political reputation in furthering his own reputation by finding a ready body of support amongst the radicals who had been inspired by Paine.

Pickering also mentions the reaction against Paine, even amongst those who shared his political ideas, created by The Age of Reason, stating, “most contemporaries (and historians, if they discuss it at all) agreed that it was Paine’s hostile attitude to religion that doomed [Cobbett’s] campaign to commemorate him with a monument to failure”. There is a great deal of weight in this, as Chapman Cohen pointed out many years ago in a booklet he wrote about Paine, but Paine was not hostile to religion, and here I feel the author has managed to confuse his opposition to the concept of personal revelation and the use of the idea to establish a system of belief. In fact, Paine actually invented a religion, which he called Theophilanthropy.

There is a strong Painite element in the story of the five Scottish martyrs as told by Alex Tyrrell and Michael T. Davis in their essay about the events and ideas behind the plan for and eventual building of Edinburgh’s Martyrs Memorial. Of the many interesting facts they record is that three of those commemorated were actually English! The authors say their contribution is an attempt to “rescue the Martyrs’ Monument from neglect and misunderstanding by demonstrating its important symbolic role in the political struggles of the second quarter of the nineteenth century”, and how it brought Scottish and English reformers together. Now, though,” they suggest, “it is assuming a new form of symbolism, namely a stress on Scottish national identity”. If they are correct, then I personally consider such a trend to be retrogressive.

There is another smaller memorial to the five, also an obelisk, in Nunhead Cemetery in London, which they illustrate with a 19th century engraving. This may be said to compliment the Edinburgh obelisk and also to transcend nationalism. Controversy surrounded the plans for the erection of the Edinburgh monument almost from the inception of the idea to have one, and this side of the saga is brought out in detail by the authors. The story of the controversy reminded me of that which broke out in Thetford in the early 1960s when a statue of Paine was offered to the town.

Perhaps the most unusual monument described in this book is the teetotallers’ monument in Preston and its associated burial ground, which is to be found in the town’s General Cemetery, though it is hardly an inspiring sight now. Preston, it seems, had the reputation, if the author of the essay Alex Tyrrell, is to be believed, and I found no reason to doubt his contention, as being the national hub for the missionary endeavours of the teetotal movement, however, as I cannot really do justice to this chapter in a short review, I shall simply say his narrative reveals a somewhat strange saga that is likely to come as something of a surprise to many students of Britain’s radical history.

In his essay on radical and trade union banners, Nicholas Mansfield presents details of a national survey, which seeks to locate and record the surviving banners. He discusses the reasons for them and their changing imagery. They were in essence a form of pictorial propaganda displayed proudly at demonstrations and parades. At one time May Day parades were awash with them, but we now we see fewer and fewer of them, perhaps this is symptomatic of the decline in the number of trade union branches as the unions have centralized their organisational structures. The preservation and recording or surviving banners froM our political past is important.

The chapter titled ‘The Chartist Rites of Passage: Commemorating Feargus O’Connor’, also contributed by Paul A. Pickering, is primarily a description of two monuments to him, one, a Gothic obelisk in London, the oiler a statue in Nottingham. The campaigns to raise the finance for them, particularly that in the capital, along with the inevitable controversies the proposed monuments gave rise to, are retailed in detail. In Nottingham, the opposition was political, but tactically concealed by being represented as concern over erecting it in a public park known as Arboretum. However, the statue was eventually placed there and can be seen to this day, although how many of those who use the park for recreation, or as a convenient right of way, know anything about the person commemorated, or of Chartism, is debatable.

The final essay commences with reference to the unveiling of a monument to Thomas Clarkson in Westminster Abbey, although Clarkson, as is pointed out by the authors, Alex Tyrrell and James Walvin, had no desire to be commemorated there. He was a radical whose reputation has been unjustly eclipsed by that of Wilberforce, for whom he appears to have acted as a sort of researcher. His opinions were of the radical Quaker variety, and he was the author of a three-volume work on Quakerism published in 1806. Nor was he, unlike Wilberforce, indifferent to the fate of the free white “slaves’ labouring in English factories. In respect to Wilberforce, the authors quote approvingly E.P. Thompson’s assertion that he, ‘turned the humanitarian tradition into a counter- revolutionary creed and left it warped beyond recognition”.

Contested Sites deserves a wide readership. It contains much I found new and it has prompted me to wonder what other radical monuments lurk forgotten around the country and also what might be said to constitute one. Perhaps here we have a neglected area of research for local historians. If I have any reservations about this book it is the price, this may prevent many who would benefit from reading it doing so. One might hope, then, that public libraries will stock it, but tight local authority purse strings might well prevent many doing so.