By Derek Kinrade

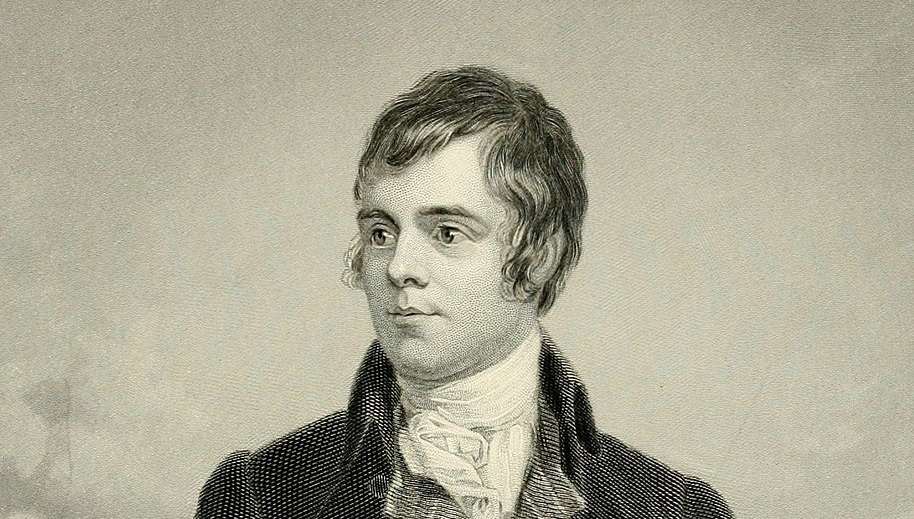

When I joined the ranks of His Majesty’s Customs & Excise in 1946, I was quickly made aware of the department’s historic literary tradition, led by Geoffrey Chaucer, Adam Smith, Robert Bums and Thomas Paine. But even after nearly 200 years there seemed to be a question mark over the last of these famous men. Paine had twice been dismissed from the service, and was subsequently charged with sedition, prompting his escape to France. Bums, by contrast, appeared to be revered without reserve, though I eventually discovered that during his Excise years he too had found himself in hot water, when some of his writing and activities had called his political loyalty into question. But the two men had much more in common than their time in the service of the Crown.

There is a substantial academic literature about both Bums and Paine (in the latter case, some of it hostile). Biographies include splendid modem works by Robert Crawford (Bums) and John Keane (Paine), along with a forensic analysis of Burns’ radical tendencies by Liam Mcllvanney. But although both lives have been well chronicled (albeit separately), I hope there may be merit in a short selective account of the most salient features of the common radical ground shared by the two great writers, and its inspiration, a comparison that has attracted scant attention. I will not attempt condensed biographies outside that narrow focus: that would neither be possible, nor necessary.

Parallels can first be found in their origins and upbringing. Both had working class roots in rural surroundings, environments and experience that inevitably conditioned their views. It is unsurprising that both found resonance in the religious and political dissent of the 18th century.

Paine’s childhood home was close to Thetford gallows and within the purview of the ruling Grafton family. He could not have failed to be aware of the rough justice handed down to the rural poor and the contrasting privilege and power enjoyed by the landed gentry. In Scotland, Bums knew from his own painful experience the penalties of toil and labour, made futile by poverty. Drudgery and hunger racked his body, but they could not vanquish his spirit, his humour, or his innate genius. The result was, to quote Barke, that “his sympathies were for the poor, the oppressed… He hated all manner of cruelty, oppression and the arrogance of privilege and mere wealth.”

Likewise, both men, as children, were exposed to religious ideology. In Paine’s case direct evidence is limited, but we know at least that his parents belonged to different branches of the Christian faith – his mother to the established church, his father to the dissenting Quaker sect – and that he had regular contact with the teaching of both traditions. Although never an atheist, it appears from his later writings that he was not persuaded by either theology. He said in The Age of Reason: “from the time I was capable of conceiving an idea, and acting upon it by reflection, I either doubted the truth of the Christian system or thought it to be a strange affair.” But more important than the influence of parental indoctrination is the evidence of Paine’s voluntary association with Methodism. There is a record that he heard John Wesley preach on one of his several visits to Thetford. Later, as a 21 year-old, he is said to have preached as a Methodist in both Dover and Sandwich. Eight years later, while in London waiting for an Excise vacancy, he is said to have again turned to occasional preaching. There is even a suggestion in the Oldys biography (repeated by Conway) that Paine sought from the Baptist minister Daniel Noble an introduction to the Bishop of London with a view to ordination. It is certainly reasonable to think that Methodism appealed to Paine. Its preachers were enthusiastic and able to reach out to the common people. They emphasised that Christ died for all, and their message, although concerned with spiritual salvation, was in tune with the 18th century radical aspiration towards equality. Notwithstanding Paine’s later assault upon organised religion and his repudiation of the Bible, Keane’s view “that his moral capacities ultimately had religious roots” is very persuasive.

Bums was baptized and brought up in the Christian faith. His father William, a strict Calvinist, was committed to his sons’ religious education, though the tone of it was somewhat tempered by the preaching of his parish minister. William Dalrymple was of the Presbyterian persuasion: a moderate, liberal man, antagonistic to divisive sectarianism, zealotry and hypocrisy, concerned to reach out to the poor, and an advocate of amity and love. Although Bums later strayed from his father’s model of piety and virtue

(particularly in his sexual inclinations: according to Berke he had passionate relationships with many women, productive of fifteen children, six out of wedlock) this early teaching was later reflected in many of his poems. And despite his departure from the constraints of Presbyterian theology, he never relinquished his belief in God. Crawford notices a manual written by Bums’s father addressing some of the fundamental questions of religious belief. One of these not only conditioned his children but, as I will mention later, was also very much in line with Paine’s thinking:

Q. How shall I evidence to myself that there is a God?

A. By the works of Creation; for nothing can make itself and this fabrick of nature demonstrates its creator to be possessed of all possible perfection, and for that cause we owe all that we have to him.

Similar parallels apply to the relatively brief formal education of the two writers. At the age of seven, Paine was fortunate to gain a place at Thetford Grammar School, but left when only twelve to serve for the next seven years as an apprentice in his father’s business as a maker of stays. But as a young man, over time, he cultivated the friendship of a number of distinguished men: the Scottish astronomer and instrument maker, James Ferguson, destined to become a Fellow of the Royal Society; the well-known lexicographer and optical instrument maker, Benjamin Martin; the celebrated astronomer and Fellow of the Royal Society, Dr. John Bevis; the writer, Oliver Goldsmith, and crucially the influential Benjamin Franklin, whose support helped Paine to establish himself in America. During his time in London he extended his reading, and met like-minded people who were challenging orthodox theology and the concept of top-down government. He was introduced, as Keane puts it, “to a new culture of political radicalism that rejected throne and altar”, and experienced a long- term conversion to republican democracy.”

Burns’s first formal education was even shorter, spent between the ages of six and nine in a local school at Alloway Mill, before having to leave to help on his father’s isolated farm at Mount Oliphant. He was, however, fortunate through those years in having a young, inspirational teacher, John Murdoch, who before his departure to Dumfries imparted a thorough grounding in the technicalities of language, with an expectation far wider than was customary for children of such tender years. This, combined with Bums’s voracious and wide-ranging reading, established a literary disposition that would prosper against the grain of physical labour and frugal living on the land. Much credit for that is also due to Bums’s father. Despite the necessity of setting his sons to farming, William Burnes contrived to continue their education at home, conversing with them as adults, and procuring books for them designed both to nurture their faith and spur their imaginations. It was fortunate, too, that in 1772 Murdoch returned to teach at another school in Ayr and was concerned enough to find time to sustain intermittent contact with the Bums brothers in pursuit of their development. Unlike Paine, Bums could not yet add personal acquaintance with leading intellectuals, but he did so at second- hand, gleaning counsel from literature, not least Arthur Masson’s Collection of English Prose and Verse and John Newbury’s anthology of letter-writers of distinguished merit.

In 1777 the family moved to Lochlea. There, although still committed to hard labour in the fields, Bums was not without friends. As he reached manhood he found particular inspiration among the Masons of Tarbolton, warming to their principles of friendship, benevolence and religious toleration. But the final shaping of Burns’s muse was forged in the depths of adversity. His problems during 1782 to 1784 have been well documented: a business venture that literally disappeared in flames; a breakdown of mind and body; the failing family farm, with the prospect of utter destitution; his father’s legal struggle in the face of a writ of sequestration. Bums’s response, as Crawford puts it, was to write his way out of it. Surrounded by deep recession and gloom across rural Scotland, he fixed upon ideals that would underpin his later poetry: dignity in poverty and admiration for men of independent minds, prepared to reject the lure of wealth and position. In 1783 he began his ‘Commonplace Book’, and gradually his identity as a ploughman gave way to that of a poet and the emergence of his distinctive style and language. By the following year he had come to think that he might be capable of exposing his work to a wider public. And among many strands of his eager imagination were political ideas drawn from his harsh, personal experience that were pointedly radical in their day.

The legal action against Bums’s father was decided in his favour in January 1784. By then, however, he was exhausted and ill, dying a few weeks later. Throughout the travails of their lives at Lochlea, Bums and his brother had respected their father dearly. But his death and release from debt, allowed a move to Mossgiel, a new beginning, a freer lifestyle and the burgeoning of Robert’s romantic poetry.

Quite when Paine moved from personal conviction to written advocacy remains unclear. More than once he insisted that he wrote nothing in England, though appearances suggest otherwise. What is certain is that in January 1775, having overcome a serious illness picked up on the voyage to America, he was taken on as editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine. Articles and poems in this new periodical and in William Bradford’s earlier Pennsylvania Journal appeared anonymously or under pseudonyms, but it is generally accepted that Paine was the author of a number of them, including a broadside against slavery, an exposure of cruelty to animals, and a plea for women’s rights. The battle of Lexington in April 1775 stirred him to give vent to increasingly radical views about British tyranny, and to consider the necessity of using force to secure human liberty. In July 1775 he penned a song Liberty Tree, the final verses of which were unequivocal in their call for revolution:

But hear, 0 ye swains (`tis a tale most profane).

How all the tyrannical pow’rs,

King, Commons, and Lords, are uniting amain’

To cut down this guardian of ours;

From the east to the west blow the trumpet to arms,

Through the land let the sound of it flee:

Let the far and the near all unite with a cheer,

In defense of our Liberty Tree.

In the Journal of October 1775, Paine (as Humanus) followed this with an article headed A Serious Thought in which he reflected on the barbarities wrought by Britain, particularly the importation of negroes for sale. He declared that he would “hesitate not for a moment to believe that the Almighty will finally separate America from Britain”.

His direct, terse and incisive prose appealed to the common citizen, and found its most positive expression with the publication, in January 1776, of his seminal pamphlet Common Sense. I need not recapitulate the arguments of this famous text, save to notice that its opening pages drew on ingrained tenets of English radicalism, with an insistence on natural rights to liberty and a vision of a new world order. Its impact was, of course, dramatic and a major factor in setting the course in favour of the war of independence.

Chronologically, Burn’s literary debut came ten years later, with the publication in July 1786 of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (the so-called Kilmarnock edition). Bums was then only 27, some ten years younger than Paine had been at the time of his first Pennsylvania articles. The collection was a chosen, wide-ranging miscellany of 36 poems, verses, songs, odes and dirges, previously written alongside his farming at Mossgiel. One reviewer thought the love poems “execrable”, and most critics regretted that they were written in some measure in “an unknown tongue” which limited their audience to a small circle. But there was general recognition of Bums as “a native genius”. He was seen as the ‘ploughman poet; a phenomenon bursting from the obscurity of poverty and the obstructions of laborious life”. Yet in all this, only two reviewers briefly mentioned occasional “libertine” tendencies, dismissed as regrettable but excusable in the light of his origins.

In fact, the edition contained three overtly political poems, written shortly before publication: The Twa Dogs, A Dream, and The Author’s Earnest Cry and Prayer. Like all the other pieces, they pre-dated Burns’s Excise service, and, according to his Preface, had not been “composed with a view to the press°. Nevertheless, one can perhaps detect a note of caution in Bums’s approach. He commonly made a virtue of his low social standing and used the paradox of a simple bard appealing to a refined audience.

The Twa Dogs is a gem. Briefly, the dogs are represented as friendly observers of the lives of their keepers: one a local dignitary, the other a ploughman. The poem, masterly crafted, contrasts the pleasure-seeking, self-interest and dissipation of the gentry (leaving aside “some exceptions”) with the destitution and toil faced by the poor, who nevertheless, in their respite from labour, find joy in the simple, frugal, common recreations of rural life:

A countra fellow at the pleugh,

His acre’s till’d, he’s right enough;

A countra girl at her wheel,

Her dizzen’s done, she’s unco weel;

But gentlemen, an’ ladies warst,

Wi’ ev’n down want o’work are curst

They loiter, lounging, lank an’ lazy;

Though deil-haet ails them, yet uneasy:

Their days insipid, dull an’ tasteless;

Their nights unquiet, lang an restless.

A Dream began with a vindicatory preamble:

Thoughts, words and deeds, the Statute blames with reason; But

surely Dreams were ne’re indicted Treason.

Bums went on to pretend that he had fallen asleep after reading Thomas Warton’s Laureate’s Ode for His Majesty’s Birthday, 4 June 1786, and in his dreaming fancy had imagined his own, alternative address. It was a daring device, for whereas Warton’s ode had lavishly flattered George III, Bums’ satire made it clear that he would do no such thing, but instead addressed the king with mock reverence, feigning loyalty while favouring defection, reminding him of the embarrassment of the loss of the American colonies and the failures of his ministers. He hoped that the King might wring corruption’s neck, and reduce the burden of taxation: levied till ‘old Britain’ was fleeced until she had ‘scarce a tester’ (an old Scots silver coin of small value). A cloak of pretended adulation and a representation of being but a humble poet might not normally have been enough to escape dire retribution, but Bums destiny appears somehow to have been charmed.

The Author’s Earnest Cry and Prayer was addressed to the Right Honourable and Honourable Scotch representatives in the House of Commons. Bums again began with mock deference: To you a simple Bardie’s prayers are humbly sent. But thereafter his 25 stanzas and postscript of a further seven were unmistakably critical: an ironic blast against the 45 Scottish members, apparently supine in the face of legislation to increase the duties on whisky:

In gath’rin votes you were na slack;

Now stand as tightly by your tack:

Ne’er claw your lug, an’ fidge your back,

An’ hum and haw;

But raise your arm, an’ tell your crack

Before them a’.

He followed this with a swipe at those whose ranks he would shortly join:

“damn’d excisemen in a bustle”!

But his main thrust was aimed at the liaison of Scottish and English members, which he clearly saw as an unholy alliance:

Yon mixtie-maxtie, queer hotch-potch, The Coalition.

An opinion that, albeit in a different context, has a certain resonance today.

In 1787, though written in 1784, a further political offering appeared in a second expanded edition of Bums’s poems, published in Edinburgh. This was a ballad conveying his thoughts on the American Revolution. Aware that it might be thought “rather heretical”, he had decided not to publish it in the Kilmarnock edition, but later, with the advice of Lord Glencaim and Henry Erskine, caused it to be included in the new edition. Whereas Paine, in 1776, had fomented the war of independence, and throughout had continued to support it in eight issues of The Crisis (the last in April 1783), Bums now reflected, after its conclusion, on the tide of events. Though the facts were no doubt gleaned from other sources, it remains a brilliant and witty summary of the hapless record of Britain’s generals and politicians, remarkable for having been constructed alongside the drudgery of Bums’s ordinary occupation.

For some years Bums added almost nothing to his political output. To make ends meet, he joined the Excise service as a common gauger, receiving his commission in 1788 and starting work in September 1789. Like myself, a condition of appointment required a pledge of allegiance to the monarch. While his poetic output was undiminished, he was now on the whole careful either to avoid contentious political issues or to try to ensure that controversial material did not appear over his name.

Not so Paine, who was in Paris during the winter of 1789-90, seeing for himself and documenting the beginnings of the popular revolution. In January 1790 he wrote enthusiastically to his friend Edmund Burke, intimating that the French Revolution was “certainly a forerunner to other revolutions in Europe”. The reaction from Burke, a supporter of the American Revolution, was unexpected. We now know that he had already been mightily disturbed by Dr Richard Price’s address A Discourse of the Love of Our Country, given at the London Revolution Society on 4 November 1789. Rather than welcoming the new revolutionary movement, Burke denounced it in his vitriolic Reflections on the Revolution in France, published on 1 November1790. This drew from Paine his famous response, Rights of Man, published in two parts, brought together in February 1792, drawing inspiration from France and making the case for the government of the people. Despite huge sales (in Britain alone, 200,000 by 1793), public opinion was divided. Those who ached for reform saw the French National Assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of Citizens as a most desirable model for Britain; many had found in the American Revolution a prospect for change, and in the French uprising a hope that a new politics might flourish in Europe. Whereas Burke, along with the government and entrenched conservative opinion, viewed the events across the Channel with alarm, dreading the possibility of civil resistance and copycat disturbances; the more so as violence and vengeance escalated in Paris. In May 1792 George III issued a Royal Proclamation against sedition, subversion and riot. In September, Paine, indicted to stand trial on a charge of promulgating seditious libel, and under constant harassment, escaped to France. He was, of course, later tried in his absence, found guilty, and vilified by the ruling establishment.

Burns was undoubtedly aware of the furore created by Paine’s pamphlet, and sympathetic to the reformist view; but also acutely conscious that as a government officer, needing the salary that went with the job, he must not parade his sentiments. He was careful to require that his poems should bear his name only with his agreement. However, on 30 October 1792 this show of neutrality was severely tested. In the newly opened Theatre Royal at Dumfries, with friends, he was in the pit for a performance of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, also attended by some of Scotland’s elite. When at the end of the play God Save the King was called for, there were shouts from the pit for ca ira, the song of the French revolutionaries. Scuffles accompanied the singing of the national anthem, through all of which Exciseman Burns remained in his seat.

There could be no real doubt as to where Bums’s heart lay. Four weeks later he wrote to Louise Fontenelle, a touring London actress he admired, offering her an ‘occasional address’ to use on her benefit night on 26 November. The Rights of Woman, published anonymously in The Edinburgh Gazetter on 30 November, all too obviously echoed that of Paine’s notorious, inspirational text. Harmlessly, Burns extolled female rights as those of protection, decorum and admiration; far more interesting, however, are the lines with which he topped and tailed his thoughts:

While Europe’s eye is ftx’d on mighty things,

The fate of empires and the fall of kings;

While quacks of State must each produce his plan,

And even children lisp the Rights of Man;

Amid this mighty fuss just let me mention,

The Rights of Woman merit some attention.

When awful Beauty joins with all her charms,

Who is so rash as rise in rebel arms?

But truce with kings, and truce with constitutions,

With bloody armaments and revolutions,

Let Majesty your first attention summon:

Ah! Ca ira! The Majesty of Woman!

As the year drew to its close, and Burns became more confident of what he believed to be the impending triumph of the British reform movement, he was quite unable to restrain his feelings, giving vent to a ballad, Here’s a Health to Them That’s Awa. This unreservedly raised a series of toasts to reformers over the border. Its message was undisguised:

May Liberty meet wi’ success’

May Prudence protect her frae evil!

May tyrants and Tyranny tine i’ the mist

And wander their way to the Devil!

Here’s freedom to them that wad read,

Here’s freedom to them that would write!

There’s nane ever fear’d that the truth should be heard

But they whom the truth would indite!

And wha wad betray old Albion’s right,

May they never eat of her bread!

Sadly, Burns’s optimism was misplaced. Doubts about his loyalty had been brought to the notice of the Excise Commissioners, who promptly launched an inquiry. Learning of the Board’s misgivings, and fearful of the consequences, Burns wrote on 31 December 1792 to one of the Excise commissioners, Robert Graham of Fintry, to assure him that any such allegation was unfounded, in that he was devoutly attached to the British Constitution “on Revolution principles [i.e the 1688 ‘Glorious Revolution’], next after his God”. Remarkably, Graham promptly responded on 5 January to reassure Bums that his job was safe. And, by return, Bums then replied to the specific allegations, admitting that he had at first been an `senthusiastic votary” of the French Revolution, but had altered his sentiments when France came to show her old avidity for conquest. Some writers have judged that the tone of Bums’ letters was contrite, even abject; that effectively he renunciated his reformist stance. This is certainly the feeling they convey on first reading; but Mcllvanney makes a convincing case that on closer analysis there was no apostasy and no apology.

Yet the detail of all this is perhaps beside the point: it seems obvious that what kept Bums in his job was his high artistic reputation and good standing, based on the fame his poetry, then as now largely focused on its sentimental, urbane and apolitical content. He was fortunate to have a number of friends and supporters in high places, not least Graham; a relationship that may fairly be judged from a ballad of 1790, which opens with the lines:

Fintry, my stay in worldly strife,

Friend o’ my Muse, friend o’ my life,

The brush with authority has attracted microscopic attention, and certainly made Bums anxious for his future. But it must also be seen in the context of explicit violent agitation in France, where, exactly at this time, Paine was in Paris, passionately — but unsuccessfully – seeking to convince his fellow deputies of the National Convention that Louis XVI should be spared the guillotine.

The Excise inquiry reminded Bums of the dangerous ground of radical poetry. Indeed, with the execution of Louis on the 21 January 1793 and the French declaration of war on Britain on 1 February, the reform movement as a whole was forced to wake up to the perils of open defiance. For the time being the State’s policy was one of such severe repression as to drive radical opposition into hiding. But at the time of the dramatic Scottish sedition trials of August 1793, Bums could no longer contain his feelings. He ventured three poems, based on the legendary heroics of Robert Bruce, all of which carried parallels, for those who could see them, to the then contemporary challenges to Scottish liberty; as Mcllvanney puts it “the tendency to view one struggle for liberty through the optic of another.” The most famous of the three, sent to trusted friends and published anonymously in The Morning Chronicle on 8 May 1794, is Scots Wha Hae, with its stark call to resist “chains and slavery° Unambiguously, through the words of Bruce, it brings the challenge into Burns’ own time – “Now’s the day, and now’s the hour”- and ends with the appeal from the lips of Bruce:

Lay the proud usurpers lowl

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!

Let us do, or die!

Bums followed this up with an Ode for George Washington’s Birthday, comparing the liberty achieved in America with the political suppression imposed from London. Although he could not then openly publicise his views, this clarion call now reveals the strength of his true feelings:

But come, ye sons of Liberty,

Columbia’s offspring, brave as free,

In danger’s hour still flaming in the van,

Ye know, and dare maintain, the Royalty of Man!

Here Bums is no longer the humble bard; there can be no mistaking the contemporary relevance of his historical allusions.

By this time, Paine had written the first part of his passionate but controversial essay The Age of Reason: being an investigation of true and fabulous theology. The astonishing story of how he took up the subject while fearing for his life is too well known to need repetition; indeed the prefaces to the first and second parts of the eventual book, separated by his incarceration in the Luxembourg prison, largely describe the perilous circumstances that attended its completion and survival. The French Revolution had turned sour. The libertarian principles that had marked its beginning had given way to bloody retribution. Paine, whose name was on the death list, had for many years intended to express his opinions on religion, and felt that he now had no time to lose. Part one appeared during February 1794, and part two, expanding his first thoughts, came out in October 1795. Together they presented the reader with a double paradox: firstly, the essays unequivocally repudiated belief in the Bible as the authentic ‘Word of God’, but by no means repudiated God; secondly, though despising the purveyors and apparatus of organised religion, there was also a recognition that the eradication of Christianity in favour of a revolutionary dogma of equality and liberty could lead the French state towards atheism. As Paine explained at the beginning of his first essay:

The circumstance that has now taken place in France of the total abolition of the whole national order of priesthood, and of everything appertaining to compulsive systems of religion, and compulsive articles of faith, has not only precipitated my intention, but rendered a work of this kind exceedingly necessary, lest in the general wreck of superstition, of false systems of government, and false theology, we lose sight of morality, of humanity, and of the theology that is true.

As usual, Paine wrote with clarity and raw honesty, appealing to reason. He saw the Old Testament as “a history of the grossest vices and a collection of the most paltry and contemptible tales”, and the so-called ‘New’ Testament as being of doubtful provenance, lacking authenticity, heaping hearsay upon hearsay, and replete with irrational, fabulous inventions and contradictions. While not doubting the existence of Jesus Christ, he regarded him as merely “a virtuous and an amiable man”. On a questionable base of “wild and visionary doctrine”, the church had “set up a system of religion very contradictory to the character of the person whose name it bears…a religion of pomp and revenue, in pretended imitation of a person whose life was humility and poverty.” Nor was this type of construction limited to Christianity. Every national church or religion “had established itself by pretending some special mission from God, communicated to certain individuals”, each with books which they call ‘revelation’, or the word of God.

Paine’s own belief was simpler. He believed “in one God, and no more” and hoped for happiness beyond this life. He expressed belief in the equality of man, and argued that religious duties consisted of doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow-creatures happy. He saw God as the compassionate creator, evidenced by creation, whose choicest gift was the gift of reason. In the first part of the essay there is a particularly interesting passage:

That which is now called natural philosophy, embracing the whole circle of science, of which astronomy occupies the chief place, is the study of the works of God, and of the power and wisdom of God in his works, and is the true theology.

Paine’s polemic excited huge interest, reinforcing those of a radical persuasion, but surely making more enemies than friends. Crucially, in Britain, those in gilded positions in the liaison of established church and state chose to see it only as an assault on cherished beliefs and values, a threat to good order and their own positions. Some, who cannot have read the essays, dubbed Paine an atheist. This he emphatically was not, but he undoubtedly provided his opponents with ammunition to confirm in their eyes his reputation as a disreputable trouble-maker.

Those who had welcomed the French Revolution as the dawn of a new age clung tenaciously to its original thinking in pursuit of liberty. In 1795, Bums, though still employed in the Excise (acting- up as supervisor at Dumfries), and having felt duty-bound to enlist in the Royal Dumfries Volunteers, nevertheless contrived to write his most celebrated political song. Popularly known as A Man’s a Man for a’ that, it first appeared anonymously in the Glasgow Magazine of August 1795. James Barke, in his edition of Bums’ poems and songs, has aptly described it as “the Marseillaise of humanity”. Disparaging the ‘tinsel show” of rank and title, Bums extols the merits of the honest man of independent mind. As others have noticed, the short verses echo the sentiments of Paine’s Rights of Man, while Marilyn Butler has pointed out that the closing lines closely follow the letter and spirit of the revolutionary song ca Ira!:

Then let us pray that come it may

(As come it will for a’ that)

That Sense and Worth o’er a’ the earth

Shall bear the gree an’ a’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that, It’s comin yet for a’ that,

That man to man the world o’er

Shall brothers be for a’ that

Paine struggled on until 1809, adding a number of less well-known studies to his archive, and at the last declining an attempt to have him accept Christ as the Son of God. Bums, like Paine, never surrendered his belief in a benevolent God. He died in 1796, still impoverished but a radical exciseman to the last. There is nothing to suggest that the two men ever met, but there may yet be one unremarked final parallel. Another version of The Liberty Tree, although never quite proved to be the work of Bums, bears the hallmarks of his style. Here then, to close, are the last two verses of eleven:

Wi’ plenty o’ sic trees, I trow

The wand would live in peace, man.

The sword would help to mak’ a plough,

The din o’ war wad cease, man,

Like brethren in a common cause,

We’d on each other smile, man:

And equal rights and equal laws

Wad gladden every isle, man.

Wae worth the loon wha wadna eat

Sic halesome, dainty cheer, man!

I’d gie the shoon frae aff my feet

To taste the fruit o’t here, man!

Syne let us pray, Auld England may

Sure plant this far-famed tree, man:

And blythe we’ll sing, and herald the day

That gives us liberty, man.

Sources:

- James Barke (ed.): Poems and Songs of Robert Bums (Collins, 1960)

- James A Mackay: A Biography of Robert Burns (Mainstream, 1992)

- Robert Crawford: The Bard: Robert Burns, a Biography (Pimlico, 2009)

- Liam Mcllvanney: Burns the Radical: Poetry and Politics in Late Eighteenth Century Scotland (Tuckwell Press, 2002)

- And, of course, the works of Paine and Burns referred to in the text.