By Michael T. Davis

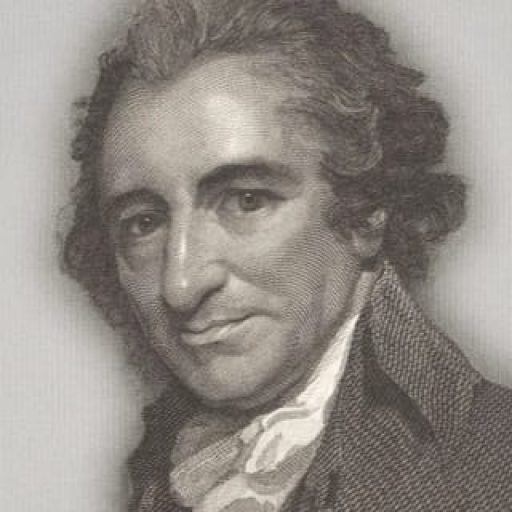

Thomas Paine’s reputation reached a pinnacle during the 1790s. His ideas divided public opinion and very few knew nothing of his writings. One was either a radical or a conservative – a supporter or a detractor of Paine. David Rivers was perhaps one exception. He sat uneasily on the fence between a friend of Paine the author and a foe of Paine the political philosopher. As a dissenting minister of a congregation at Highgate, Rivers perhaps found hostility to Paine after the publication of The Age of Reason, but he was prepared at least in part to concede that Paine was an eminent writer.

Rivers himself had issued several anonymous pamphlets, including a sermon on ‘The Gospel a Perfect Law of Liberty’ and a sermon against Popery. He was a frequent contributor to the World newspaper and the Sunday Recorder To this day, other details of his life remain an unsolved mystery.

In 1798, Rivers published his “Literary Memoirs of Living Authors of Great Britain”. (A copy of Rivers’, Literary Memoirs of Living Authors of Great Britain. 2 vols. (1798), has been reproduced by Garland Publishing, New York, in 1970, from a copy of the original held in Yale University Library.) In it he found room to devote one of the largest entries to Thomas Paine. It provides an ideologically biased account of Paine’s life to 1798, but its value lies not in the biographical details it recalls. In the very least, this memoir can be used to gauge contemporary opinions and is indicative of the great – and to some, fearful – importance of Thomas Paine.

Literary Memoirs is not highly consistent in its split between radical and conservative. John Bowles and Hannah More receive favourable entries, whilst the prophet-visionary, Edward Brothers, is dismissed as a “mad enthusiast” (p.71). Surprisingly, one of Paine’s most ardent supporters, Thomas Clio Rickman, receives a brief memoir that records nothing of his radical zeal. Rivers memoir of Paine shows to some extent this same inconsistency. As the following excerpt illustrates, Rivers acknowledged Paine’s status as an author, but strongly denounced the ideology of his writings:

‘We come now to the period of Paine’s History, when his speculations were to shake the fabric of the public mind to its very foundation, and his writings to infuse a poison among a deluded commonality, the effects of which, to a philosopher in the shade, would have been scarcely credible… The abuse which has been so liberally bestowed upon Paine, as a writer, has, perhaps, for the most part, been the result of a zeal whose tendency is to weaken, more than support, its cause. Let us rather allow him, the unqualified credit of an animated, energetic writer, who displays considerable acuteness but whose manner of thinking is rude, wicked and daring, and whose language is vulgar though impressive. Let us rather rejoice, that Englishmen, with their just veneration for civil liberty and the rights of the people, were found so wise and stedfast (sic) in an hour of danger, as to despise those sorry calculators, that would perstr, ie a country, whose constitution has raised her to be the envy of all the civilised world, to hazard that constitution upon the grossest, clumsiest, and stalest theories. Let us be thankful that the arch-theorist of the Rights of man, of those rights which transfer the reins from his passion to his reason, of those rights which dissolve ties, which confound distinctions, which destroy security, could play upon us with his new lights upon human governments, without dazzling our reason, or impairing our eye-sight Finally let us rejoice, that when this when this wily and audacious Anarch dared, at last, to attack the sacred volume of our religion, there was found, on our Bench of Bishops a learned and philosophical Prelate, condescending enough and active enough to oppose them nobly and completely, by his erudition, his clearness, and his strength of argument (pp.99-104)’. (Presumably this refers to Bishop Richard Watson’s, Apology for the Bible, published in 1796. – Ed.)