By Ellen L. Ramsay

THOMAS Paine (1737-1809), author, editor, stay maker, excise man, small farmer, inventor, citizen of three countries, military courier, first US Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly, and pamphleteer for the Enlightenment, not only built diplomatic bridges between countries at a time of conflict, but also forged plans for bridges of iron that would cross the chasm between geography and politics. As the moments of war, post-war reconstruction and currency crisis unfolded, Paine documented and unravelled politics for citizens living in an age of personal uncertainty and helped to erect a symbolic bridge into what he hoped would be an age of common sense and reason.

Thomas Paine, the man, struggled with the dual tasks of earning a living and creating a body politic. During his lifetime Paine faced jealous political opponents (some half his age) who campaigned to ruin his career and personal life, and who prepared slanderous biographies to be published before and after his death. (Moncure D. Conway (1832-1907), American abolitionist, biographer and researcher of the Paine I manuscripts discusses the biographies of Paine in his volumes, The Lift of Thomas Pals, New York: G. Putnam, vol. 1, 1892, preface, pp. ix – xvi.) Nonetheless, Paine left a legacy as a writer and a proponent of democracy that survived through the widespread support of mechanics and working class people who supported his ingenuity, honesty, and promotion of Enlightenment causes (universal suffrage, the abolition of slavery, the demise of superstition, democratic government, the creation of full employment, a welfare system, and a retirement pension scheme). His writings, distributed as pamphlets and letters to the working class of the world, also reached the ears of presidents and reformers. Nineteenth and twentieth century supporters of Paine kept his legacy alive and extended the principles of the Enlightenment so that the bicentenary of Paine’s death on June 8, 1809 will be commemorated around the world this year.

Thomas Paine’s bridge of diplomacy, both as a practical bridge and as a symbolic bridge between nations and political eras, centred on his proposal for a single span iron bridge braced by strong abutments cast from nature in the design of a spider’s web. The bridge was never completed. His bridge design and his political proposals were however taken up by others in Paine’s three countries of residence (England, the United States and France) and eventually extended around the world. Paine’s political bridge spanned three countries on two continents during a period when countries had sunk themselves under the debt of war. Faced with costly domestic reconstruction, collapsing banks, and currencies dissolving in quicksand, governments are forced to find solutions to failing domestic economies.

Thomas Paine, the bridge builder, faced his own difficulty of finding governments willing to invest in durable iron bridges to replace the wooden and stone bridges that were being swept away by strong water currents, ice and sand flows – an enduring problem for governments accustomed to short term solutions and temporary construction in an era of war. As a political reformer, Paine also tried to build bridges between regions of the world that had sunk into debt from military expenditure. The idea of political diplomacy for Paine became paramount and inseparable from governments investing in long-term civilian infrastructure projects. For this reason, the author of an early draft 775) of the American Declaration of Independence (1776) including a clause to abolish slavery, the Pennsylvania Constitution in 1776, and revisions to the French Constitution of 1791 became a designer of bridges for civilian use. (Paine’s draft of the 1776 Declaration of independence appeared in the Pennsylvania Journal on 18 October 1775 under the pennamo “Humanitas.” Paine arrived in America from England on 30 November 1774 and secured employment as a writer for the Pennsylvania Journal in 1775-6.)

Paine’s Schuylkill River bridge, designed for its fortitude, easy portability and repair, was to have thirteen columns to commemorate each of the thirteen states in the Union and was subsequently adapted to meet the political needs and practical engineering requirements of the three principal countries involved in the American War of Independence. Paine eventually offered his design to countries in northern Europe as he struggled to find an investor. The War had been an expensive war for all involved. Parliamentary reformers in England estimated that the expense from the English side alone had been £139,521,035 by 1781 and an additional £1,340,000 in compensation payments not including the £4,000 per year in stipends paid to loyalists from 1788. (Charles Bradlaugh, “The Impeachment of the House of Brunswick,” Freeihought Publishing Company 11-amts, London: Fredhought Publishing Company, 1880, p. 45.) The French incurred similar expenses for their part. In the aftermath of the war, Paine predicted the collapse of the international monetary system unless politicians rapidly learned the skills of political diplomacy and economic intervention.

Paine, an English republican, had become a supporter of American Independence and moved to the United States in 1774, one year prior to the War of Independence. He was to personally witness two revolutions in his lifetime – the American War of Independence and the French Revolution – and his contribution to American independence included serving as a government secretary, military courier and clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly, in addition to helping build the Bank of North America, a citizens’ subscription bank founded in May 1780 with his own subscription of $500. The Bank became incorporated by Congress and then by the State of Pennsylvania on 1 April 1782. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. T p. 221.) The purpose of the bank was to help fund the wounded war veterans of George Washington’s army, but the bank came under attack when it became too large and was unable to repeal its charter. Paine wrote about the general economic collapse and saved the bank with the distribution of his pamphlet entitled, Dissertations on Government the Affairs of the Bank and Paper Money (1786), in which he pointed out that the greed of the banks had caused them to lend money without proper security and that public claims had been exorbitant. He also pointed out that the debt of the banks was to be passed on to the subscribers who owed 6% interest in perpetuity on their holding while the banks continued to invest their money at 10-12% and speculators received an additional 20-30% on their investments. Paine argued against the creation of a paper currency to see the country through the crisis. Paine was left with personal financial debt as a result of the collapse of the bank and could not pay his own 6% interest in perpetuity and thus embarked on his bridge project in 1785. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol.1, p. 219. John Keane alternatively suggests that Paine Muted to bridges in a “bout of restlessness” following the war (see Keane, p. 267) and Alfred Owen Aldridge suggests Paine emerged from the Bank difficulties a rich man who was freed up by his money to pursue the bridge designs. (see Aldridge, Man (Reason The Life of Thomas Paine, Philadelphia & New York 3.5. Lippincott Company, 1959, p. 108.) This author prefers Conway’s interpretation because Conway investigated the available evidence closer to Paine’s time, and did not rely on George Chalmer’s 1793 biography of Paine.)

Moncure Daniel Conway, the American abolitionist and biographer of the Paine manuscripts, stated that Paine had been referred to in his day as a “living Declaration of Independence” and had urged Americans to turn their thoughts from war to public efforts of reconstruction. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life Thomas Paine, vol. I, p.245.) Paine was an Enlightenment inventor who had used his scientific knowledge to invent a smokeless candle, wheels for carriages, as well as wood planers and now presented the more ambitious project of an enduring bridge for public use. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, The Cobbett Papers, vol. Q, Appendix A, p. 456.) Paine corresponded with and met Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), as both a politician and an inventor; with John Trumbull (1756-1843), painter of the American Revolutionary War; and Benjamin West (1738-1820), then a court painter for George Ill.

Paine’s design for a single span iron bridge emerged at the time when iron foundries had started to turn from war production (cannons and cannon balls) in the early 18th century to civilian production (cast iron water mains, water pipes, sewers, fire engines, canals, door hinges and locks, water wheels and garden fences) in the late 18th century. The new technologies of iron ore smelting and iron casting came about as a result of the exhaustion of the tree stock that had fuelled the wars and industry of Europe from the 17th century. New fuel was required to replace the dwindling tree stock and coal used in the refining of iron ore by smelting charcoal became an alternative.

The first attempt to build a cast iron bridge is generally agreed to have taken place in Lyon, France in 1755. The next is believed to have been the Coalbrookdale Bridge (1777-1779) on the River Severn in England. By 1750 coke smelting had been established in Coalbrookdale, and the Coalbrookdale Company was able to build a bridge with a design by Thomas Farrols Pritchard (1723-1777) completed by Abraham Darby Ill (1750-1791) who worked with the Coalbrookdale Company. A shortage of pig iron meant that iron ore had to be imported from Norway, Spain, Sweden and Russia. There was, however, a plentiful supply of coal from the fossilized remains of the old tree stock of Europe and in America.

By 1783 and the Treaty of Paris, the best American trees had been cut to build English warships. The domestic use of trees in the United States had been severely restricted during the colonial period and only in the late 18th century were trees even considered for use in major bridge building projects. Oak was considered the wood of choice. (John Keane, Torn Paine: A Political Life, Boston: Little, Brown and Company. 1995, p. 267.) America therefore embarked on a period of wooden bridges at a time when Europe was infatuated with the idea of more durable iron bridges. Thomas Paine, in his designs for an iron bridge in America pointed out that wooden bridges were impractical for a climate of freezing temperatures, ice, sand, silt and mudfiows, and unstable river basins. Pennsylvania seemed a good state in which to erect his first iron bridge for both pragmatic and political reasons since it was a state both rich in coal and the first state to broker independence from Britain. (Moncure D. Conway, Addresses and Reprints, 18504907, Boston and New York: The Riverside Press, 1909, pp. 403-406.) In 1785 Paine had completed his plans for bridges over the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, the Harlem River in New York State, the Thames River in London, and the Seine River in Paris. While he waited for acceptance of his designs in one place, he moved on to the next and tried to take with him a bridge of diplomacy while awaiting a practical bridge of peace.

The success of the Coalbrookdale Bridge in England with its single 100 Y2 foot span over the Severn and a rise of 50 feet bearing 278 tons of cast iron on a thrust principle on strong masonry abutments demonstrated to Paine the success of the cast iron technology for a wide stream bridge with high arches to allow the passage of boats. The Coalbrookdale Bridge had proved that iron could provide a secure material capable of withstanding strong currents on a river basin of clay, rock or chalk. (F.W. Sims (Ed), The Public Works of Great Britain, London: John Weald Architectural Library, 1838, n.p.) Cast and wrought iron bridges proved easy to transport in sections, repairable and highly durable due to the diagonal tension of bow and string suspension and were subsequently initiated all over the world. (Capt. A.H.E. Boileau; Outline of a Series of Lectures on Iron Bridges Delivered at the Calcutta Mechanic’s Institute on 1841, Calcutta: Mechanics’ Institute, 1842, pp. 2-9; Hamilton Weldon Pendred, Iron Bridges of Moderate Span, London: Crosby Lockwood and Co., 1887, pp. I24,140-1.) Paine was just one proponent of iron bridges. When Paine began his iron bridge designs he, like others, knew that the Blackfriars Bridge in London had recently given way and two bridges over the Tyne in Northumberland (one by John Smeaton) had collapsed when the piers gave way in quicksand. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol_ 1, pp. 243, 254.)

Some biographers have credited Paine as the next pioneer of iron bridge design after Coalbrookdale although with the profusion of iron bridge designers in the period this is an unnecessary claim. Moncure Conway made no such claim and pointed out that the most enduring historians have not been concerned with hailing triumphal “firsts.” Conway presented Paine’s bridge design in more modest terms as simply an original iron bridge design, as this was Paine’s own description. Conway searched Paine’s patent of August 28, 1788 registered by Paine for “Constructing Arches, Vaulted Roofs, and Ceilings on principals new and different to anything hitherto practiced.” (John Keane records the patent date as August 26, 1788 in his volume, Tom Paine: A Political Life, p. 276.) Paine proposed the basic design of his bridge as a section of a circle with iron abutments “dividing and combining” like “the quills of birds, bones of animals, reeds, canes, Etc.” where the arch could be composed of any length “joined together by the whole extent of the arch and take the curvature by bending.” The patent was granted in September 1788. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, val. p. 242. For more on Paine’s bridge design see Moncure D. Conway, The Writings of Thomas Paine, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896, vol. IV, pp. 440-449. See also Paul Collins, -The Arch Revolutionary,” New Scientist, 6.November 2004, pp. 50-51.) Conway pointed out that the 100-foot iron arch designed by Thomas M. Pritchard and erected over the River Severn at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, did not anticipate Paine’s design and that such arguments are not appropriate to the historical assessment of Paine’s contribution to democracy and design. Conway thought it more politically important to point out that Paine remained destitute most of his life despite his political contributions. Had Paine’s proposals for bridges been adopted they would have provided him with an income. As it turned out, Paine’s political opponents attacked his small personal finances and land holdings in the United States leaving him destitute. Paine had to be buried on the small remaining portion of his farm land and then exhumed and transported overseas when the land was sold on because Paine had been unable to secure a grave plot in the local Quaker’s yard. Meeting and knowing people in high places had not advantaged Paine personally. Paine was well aware that he was being ruthlessly exploited. He kept notably quiet in political meetings apart from discussions of corporation, and the tone of his correspondence to Thomas Jefferson and other politicians became droll as he realised governments were not going to invest in his iron bridges. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 243. )

Paine hired John Hall, a mechanic from Leicester who had worked with the Boulton and Watt steam engine manufacturers, with John Wilkinson at the Coalbrookdale Company, and with Samuel Walker of Walkers and Co. in Yorkshire. (John Keane, Toni Paine: A Political Life, p. 268.) Paine and Hall shared an interest in Pennsylvania politics and in Benjamin Franklin’s election as president of the state. Paine belonged to a number of societies including the Society for Political Inquiries that met in Benjamin Franklin’s library. The Society for Political Inquiries had 42 members while Paine was a member including George Washington, James Wilson, Robert Morris, Gouverneur Morris, and George Clymer. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life Thomas Paine,vol.1, p. 225.) Hall assisted Paine with his model for a 400-foot single span iron bridge over the Schuylkill River. Paine completed the design and the mathematical side of the construction while Hall constructed the model to Paine’s specifications.

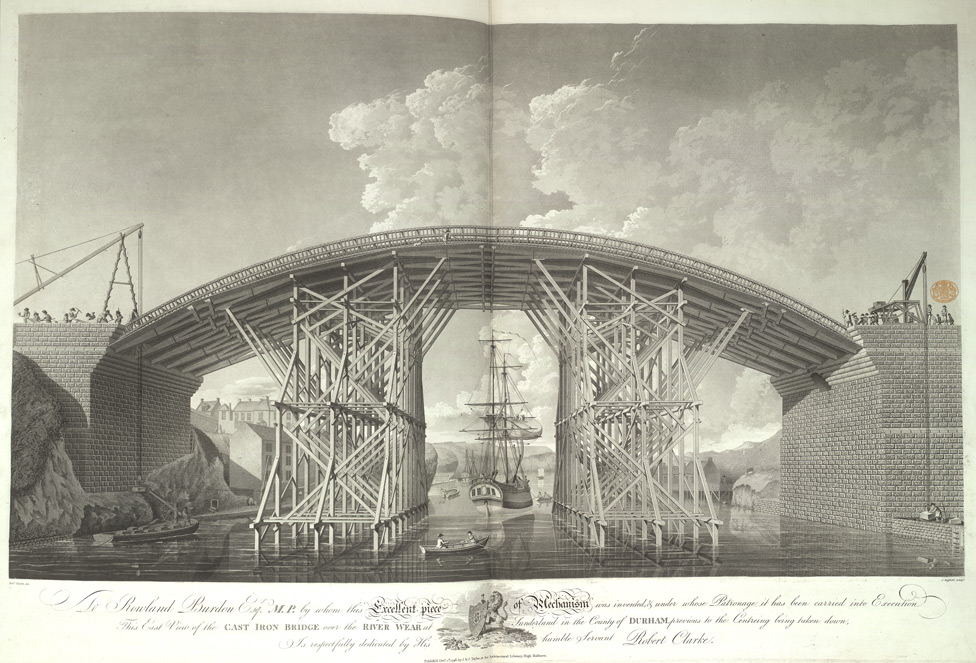

Paine and Hall presented two models for the Schuylkill River Bridge to Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, and General Morris in New York. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol.1, p. 218.) One model was constructed in wood and the other in cast iron. The Schuylkill River models stood in Franklin’s garden for some time before finally resting in Charles Wilson Peale’s Museum of Natural History in Philadelphia. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. 11. p. 318 and Appatcrut A, The Cobbett Papers, p.456.) By the nineteenth century, only one dilapidated model remained in the Peale collection, and no other bridge model was extant. It is believed that the bridge most closely resembling Paine’s was the bridge over the River Wear at Sunderland in the north of England erected in 1796 by Thomas Wilson. While Wilson’s bridge lacked the same web design it did contain circular reinforcements similar to those proposed by Paine and demonstrated that Paine’s bridge could have seen its way into a completed project. The Wear Bridge stood 236 feet in width and 95 feet in height. It was unfortunate for Paine that his bridge designs were not commissioned for he had to move elsewhere in search of work.

In 1787 Paine returned to England and applied for a bridge patent in that country. Paine proposed a bridge design for the River Thames and approached iron men in the North of England to execute a model settling on Samuel Walker of Walkers and Co. near Sheffield who recommended that it be executed in wrought or cast iron. Paine proposed a bridge of 110 feet and built a model with money he and Peter Whiteside, an American Merchant in London, had raised. The model was built at the Rotherham works in Yorkshire and was erected in June 1790 at Leasing-Green (now Paddington Green). Visitors paid one shilling per person to help raise money for the project. In the meantime Paine went to Paris and proposed a bridge project there but was forced to return to London when Peter Whiteside’s business failed. Whiteside fell £620 in debt for his portion of the bridge and Paine and the American merchants Cleggett and Murdoch had to act as Whiteside’s bail. They paid his debt and as a result Paine lost the money for his aging mother’s stipend. He then recovered the money through visits to his bridge by Sir Edmund Burke, the Duke of Portland, Lord Fitzwilliam of Wentworth House, Lord Lansdowne, Sir George Staunton and Sir Joseph Banks. However, no contracts for the bridge in England were forthcoming. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol.11, pp. 259-277.) Moncure Conway pointed out that while Paine continued to look for financial means in England and France and continued to promote the American cause overseas, “in truth America was silently publishing what they could out of a starving English staymaker.” (Moncure D. Conway, The Life ((Mantas Paine, vol. 1, pp. 244-245.)

Paine continued to propose the benefits of iron bridges over wooden bridges and to request commissions from governments in France, England, the United States and Northern Europe. (Moncure. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 220.) Moncure Conway wrote of Paine,

In setting the nation at once to a discussion of the principles of such government, he led it to assume the principles of independence; over the old English piers on their quicksands, which some would rebuild, he threw his republican arch, on which the people passed from shore to shore. He and Franklin did the like in framing the Pennsylvania constitution of 1776, by which the chasm of °Toryism” was spanned. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 1892, vol. I, pp. 224-5)

The Schuylkill River contract was not secured due to “the imperfect state of iron manufacture in America” according to a letter from Monsieur Chanut, one of Paine’s French contacts. ‘Something of the same kind might be said of the political architecture,” added Conway. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 226.) Instead, the State of Pennsylvania erected a wooden bridge over the Schuylkill River between 1798 and 1805.

Paine travelled to France with a model of his Schuylkill River Bridge in 1787 that he presented to the French Academy of Sciences in the hope that he would gain the attention of backers there or in Northern Europe. He proposed an arch of 400-500 feet to span the Seine. The French Academy met with Paine and agreed to appoint a committee to report on his bridge. While awaiting the decision Paine entered into correspondence with Thomas Jefferson who was American Minister in Paris at the time. (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 228.) The French Academy returned a cautious response to Paine’s proposal, having examined iron bridge models. They agreed with him on material points and while generally favourable they expressed a preference to one of “our own” which turned out to be a less expensive and less enduring wooden bridge by Migneron de Brocqueville. (Montana D. Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 229.) The same correspondence from the French Academy expressed an interest in the famous bridge at Schaffhausen built by Grubenmann, a carpenter; the model shown to Paine by Perronet, the King’s architect.° Paine’s bridge was never built. Paine nonetheless continued constructing a diplomatic and political bridge of friendship across the channel and sent his design to Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society in England. (Moncure D.Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. I, p. 230.)

Paine’s mother in England was now 91 years old and Paine desperately needed money to support her. While Paine’s bridge efforts had not come to fruition, Paine was granted honorary citizenship in France and elected Deputy for Pas-de-Calais to the National Convention in 1792. It is not known whether his monetary situation improved from the position but it saved him from imprisonment in England for having written The Rights of Man (1791- 2). (Moncure D. Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, vol. 1, p. 230.)

While Paine awaited decisions on his bridge he wrote Denton Emigre, an archaeological treatise on freemasonry and was nominated by the 1792 Convention to revise the 1791 French Constitution. However as the Legislative Assembly progressed and voting began to abolish the monarchy, Paine fell into disfavour for advocating that Louis XVI be tried by jury, followed by imprisonment or exile, rather than executed. Paine opposed the use of the death penalty, which he considered to be the weapon of the monarchy, and was in favour of a democratic peoples’ constitution that supported trial by jury. On 11 December 1792 Louis XVI was placed on trial before the Convention, and was sentenced to death by a political vote of 380 to 310 on 19 January 1793 and executed on 21 January 1793. (Albert Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution 1789-1799, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1977 (originally published as La Revolution Francaise, Presses Univasitaires de France, 1965.) Robespierre and his supporters in the Convention mistook Paine for a Girondist, which he was not. However, Paine was imprisoned for opposing the death penalty on December 25, 1793 and was only released on November 6, 1794 through the diplomatic work of General James Monroe, US Minister to France, who arranged for Paine to be granted American citizenship. While Paine was incarcerated he wrote, The Age of Reason (1794-5).

In 1873 Gustav Courbet, artist and Minister of Fine Arts under the 1871 Commune explained to the American abolitionist Moncure Conway that he had little time to paint a commission of artworks for the Governor of Ohio since he had been wrongly forced to pay off the debt of the raising of the Vendome column in 1871. (Ellen L. Ramsay, Moncure D. Conway: Rationalism, and the Abolition of Slavery, London: Thomas Paine Society and The Freethought History Research Group, 2007, pp. 37-38.) Paine’s bridge plans were also interrupted by revolutions, imprisonment, economic turmoil, drafts of constitutions, advice to newly formed governments, and the writing of pamphlets including Common Sense (1776), The Age of Reason (1794-5) and The Rights of Man (1791-2). Such was the historical moment that public projects proposed by Enlightenment figures such as Paine only gradually pushed their way onto the world stage in the face of the rocky road of diplomacy and post-war reconstruction that had been temporarily undermined by the canon balls of war.

Copyright 2008. Ellen R. Ramsay.

ELLEN L RAMSAY BA, MA, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of art history currently on leave from York University and has published 215 articles on art, culture and politics. She is a member of the Thomas Paine Society in England.

Selected Sources:

Paul Collins, The Arch Revolutionary: New Scientist, 6 November 2004, pp. 50- 51.

Moncure Daniel Conway (ed.), The Writings of Thomas Paine, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896.

Moncure Daniel Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, New York: G.P. Putnam, 1892.

John Gloag and Derek Bridgwater, A History of Cast iron in Architecture, London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1948.

John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1995.

Thomas Paine. The Construction of Iron Bridges, June 13, 1803, Presented to the Congress of the United States from Bordentown on the Delaware, New Jersey. Reproduced in Thomas Paine, Collected Writings, New York, The Library of America, 1995, p. 422-428.

Ellen L Ramsay, Moncure D. Conway Rationalism and the Abolition of Slavery, London: Thomas Paine Society and the Freethought Historical Research Group, 2007.