By R.W. Morrell

Although Thomas Paine is best known for his role as a revolutionary, political and social reformer and biblical critic, like many of his circle of friends and acquaintances he had a passionate interest in science, or, as it was then termed, natural philosophy. He cannot by any stretch of the imagination be described as a great scientist, although his ideas about the use of iron for the construction of bridges has given him a place in the annals of civil engineering. However, although Paine is best remembered for his political work his interest in science should not be lost sight of, for it certainly influenced arguments he advanced in The Age of Reason.

It would seem from what Paine wrote that his interest in matters scientific was clearly coupled with a strong belief that whenever possible scientific discoveries should be given a practical application. This is well illustrated from several articles he wrote, or reprinted, after he became editor of The Pennsylvania Journal In fact the first to be published under his own name in America discussed the nature and use of saltpetre, thus combining science and its application (November 22, 1775).

Paine’s interest in science led to him meeting Benjamin Franklin, with who he became very friendly. The introduction had been arranged by G.L.Scott, a member of the Excise Board who had met Franklin as a result of his own interest in matters scientific.1 The meeting was to have momentous consequences as it eventually led to Paine’s eventual departure for what were then England’s American colonies; he took with him an introduction from Franklin to his son-in-law, Richard Bache, who lived in Philadelphia. This recommended Paine as a potential clerk, teacher or assistant surveyor, the latter perhaps being indicative of his interest in science. In the event Paine found employment in none of these but became a journalist.

Thomas Paine was extremely reticent about his personal life, particularly his childhood. We can only guess at the influences upon the young Paine as he grew up in Thetford. Who sparked off his interest in science? We know not, he does not tell us. The fact of all his private papers having been destroyed in a fire does not help us to reconstruct his early years and it is likely that in all probability the gaps will never be filled. However, the few biographical references scattered around his works provide a few tantalising hints. He appears to have been interested in natural history, though to what extent he pursued the subject is unclear as he does not appear to have furthered this side of scientific studies. We find references to the distribution and habitats of insects in the first part of The Age of Reason.2 as well as observations on the habits of spiders.3 This certainly implies an interest in natural history, though whether his observations are based on study in the field or simply reading what someone else had written we cannot say. Interest in spiders, though, was never a commonplace study, nor is it now despite the existence of a society devoted to arachnology. So who influenced the young Paine in natural history? It could have been a teacher or even a fellow pupil at Thetford Grammar School, but I suspect the most likely individual was his father, who, in Paine’s own words, possessed ‘a tolerable stock of useful learning’.4 As we know of Paine’s early ambition to be ordained as a non-conformist minister,5 this might have contributed to a desire on his part to study science, including natural history, as an aid to achieving his ambition, for many clergymen of the time exhibited considerable interest in the latest scientific trends. Unfortunately, Paine’s failure to have studied Greek and Latin became an insurmountable barrier to him becoming a minister of religion, for his Quaker father objected to him studying these languages. Perhaps the real reason was that for his son to have taken up the study of Latin and Greek would have added considerably to the cost of his education, for while Paine senior might have had a reasonably good business he was certainly not wealthy. Thankfully Paine was not destined for ordination and was eventually to discard his youthful attraction to christian supernaturalism.6

In The Age of Reason Paine contrasts what he identifies as the evidence for creation and design in nature with the claims for supposed biblical revelation, viewing the former as genuine and the latter as hearsay. A believer in both a god and an afterlife, Paine viewed his deity as impersonal, though he failed to grasp the fact that his argument for the existence of a such an entity could be employed just as well to demonstrate the existence of a whole horde of them. The problem with using science to attack one form of religious belief while using it to support another is that the arguments against the one as often as not apply equally to the other. This is the problem which current besets those who have sought to reconcile evolution with judea-christian creationism and it often astonishes me just how foolish some very distinguished scientists make themselves when attempting to do so. Paine must have found it ironic that some of his more liberal christian critics, most notably bishop Richard Watson, a former professor of chemistry, were quite happy to laud his creationism but deplore his criticism of their cult. Watson, though, was not a biblical literalist and his ‘reply’ to Paine was harshly criticised by the author of many an evangelical pot-boiler, Hannah More, for actually having read The Age of Reason before replying to it. She pointed out to him that she had also replied to Paine but without having read the book she criticised. Just what Watson, a highly intelligent and sophisticated man, thought of this is not recorded. Watson had no dispute with Paine’s belief in the ‘The Word of God’ being ‘the creation we behold`.7 Though to Paine, theology was simply ‘the study of human opinions and of human fancies concerning (his emphasis) God’.8 Theology apart, Watson approvingly refers to Paine’s view of nature as being ‘animated with proper sentiments of piety’ when speaking of the structure of the universe.9

Long before he went to the American colonies Paine had studied science, primarily astronomy, and, it would appear from hints he drops, what was to become known as geology, not that he uses this term, at classes in London taught by James Ferguson and Benjamin Martin.10 Martin was an astronomer, lens polisher, instrument maker, collector of geological specimens and an accomplished writer on scientific subjects, being editor and publisher of The General Magazine of Arts and Sciences. He was, in the words of the late Dr. R.G. Daniels, ‘a general compiler of information’.11 A comparison between Paine’s The Pennsylvania Maga- zine and Martin’s General Magazine, suggests the former to have been greatly influenced by the latter’s general approach. James Ferguson was also an astronomer and instrument maker who kept a shop in the Strand where he sold globes and other scientific instruments. Paine records his acquisition of a pair of globes so it just might be that he purchased these from Ferguson.12 Another individual Paine came into contact with was Dr.Bevis, presumably Dr John Bevis, a medical practitioner, accomplished astronomer and associate of Edward Halley of comet fame who also shared Martin’s interest in collecting geological specimens. He does not appear to have liked light reading for it is recorded that his favourite reading material was Newton’s Opticks.13 Paine, too, was a believer in Newtonian concepts which one supposes he picked up long before he met his London teachers, contact with whom would reinforce his Newtonianism. However, it was left to him to apply them to areas which their originator and most of his followers would have hesitated to enter.

One of Paine’s earliest American essays, written under the name `Atlanticus’, is to be found in The Pennsylvania Magazine’s issue for February, 1775.14 This is largely geological in content, opening with a reference to the cabinet of fossils belonging to the Philadelphia Library Company. Paine’s use of the word ‘fossils’ can be a bit misleading to modern readers as in the 18th century no distinction was made between organic remains and non-organic geological material. In fact it was not until 1778, three years after Paine’s essay had been published, that JA.de Luc suggested the word geology be used to describe the study of earth history, and even then he was personally reluctant to employ it because nobody else did.15 According to Paine, the Philadelphia collection consisted of European specimens supplemented by examples of American earth, clay and sand, all with descriptive information and locations. He uses this information as an introduction to a discussion about the potential mineral wealth of the colonies as well as the effects of erosion and distortion of strata. He refers to the difficulties of determining what lies below the surface but being a practical person gives a description of an instrument, a form of boring tool, which could be employed to gain the information.16

In France, Paine met and became friends with C.F. Volney, who had written a book about his travels in Syria which contained much geological data as well as a suggestion on how to forecast the onset of earthquakes. Volney shared Paine’s radicalism, giving expression to his ideas in a book entitled, The Ruins, or Meditations on the Revolutions of Empires and the Laws of Nature, published in Paris the same year as the first part Rights of Man was published in London. In common with Paine’s book Volney’s essay was destined to be banned in Britain.

Volney had another thing in common with Paine, he was attacked by Joseph Priestly. He had gone to the United States in 1795 to avoid political persecution in France, and on return to his native country he wrote one of the most important of the early works on American geology, a two volume study entitled Tableau du Climate et du sol des Etats d’Amerique… (Paris, 1803). An English translation was published in London in 1803 (the book was not banned as it was considered to be apolitical). A year later another translation was published in the United States. This contained many notes and observations by the translator, C.B.Brown, which are of great value in themselves.17 It was while in the United States that Volney found himself under attack from Priestley, ironically another refugee from political tyranny. Priestly hit out at Volney’s Ruins with a book he entitled, Observations on the Progress of Infidelity with Critical Remarks on the Writings of Some Modern Unbelievers and Parliament on the Ruins of M.de Volney. In it he stooped to personal abuse, describing Volney as ‘an ignorant man, and scarcely superior to a Chinese or a Hottentot’, comments of a racial character which do not reflect greatly to the credit of their author. Volney replied to Priestley’s intemperate outburst in a letter published in Philadelphia on March 2, 1797. Priestley’s attack on Volney is not one his biographers have been overly keen to draw attention to.

Another popular interest amongst the 18th century intelligentsia which one might expect Paine to have taken note of was antiquarian studies, hence it need occasion no surprise to find a reference to ancient Egypt in one of his works, Crisis Paper No.5, where he writes of the knowledge the ancient Egyptians possessed about embalming having been lost and hieroglyphics being untranslatable.18 He penned this comment during the War of Independence so perhaps he was then unaware that while mummies were being imported into Europe in large numbers it was not so much for display in cabinets of curiosities, though many ended up in these, but for grinding down into a drug called mumia vera aegyptiaca,19 which appears to have been looked upon as a sort of glorified cure-all. This seems to have been the extent of Paine’s interest in archaeology in general and ancient Egypt in particular.

While Paine has nothing to say about drugs made from mummies he did attempt a contribution to medical science with an essay on yellow fever. This piece, written late in his life, was very well received by the medical profession in both Britain and the United States. Entitled, Of the Cause of the Yellow Fever; And the Means of Preventing it in Places not yet Effected with it, the short essay, which when it first appeared in London in 1806 escaped the blanket ban on Paine’s works and went through several editions. Despite its title it does not actually identify the cause, which had to wait until 1887 when it was found to be transmitted by infected mosquitoes. However, Paine correctly hit upon how the disease had arrived in America even if the actual carrier remained a mystery, for he suggested it had been carried in cargo on ships from the West Indies. Moreover, Paine’s suggestion that increasing the flow of water to clear stagnant bodies of water, in which, unknown to him, the mosquitoes bred, would have dramatically reduced the incidence of the disease, as R.G.Daniels, a doctor, noted.20 He points out that some of Paine’s ideas were similar, if not identical, to those of Sir Patrick Manson, an authority on yellow fever, as expressed in his famous textbook on tropical diseases.

Paine’s outstanding contribution to science, or, perhaps more accurately, to civil engineering, was his determined promotion of the use of iron in the construction of bridges. Several of his biographers have claimed England’s second iron bridge, erected over the River Wear at Monkswearmouth, to have been based on Paine’s design, but, as S.T.Miller clearly established in his paper on it,21 this is not the case, for the method of its construction was to utilise the iron as building blocks, a method which was neither advanced or innovative. Paine’s ideas in contrast have been described as ‘the prototype of the modern steel arch’, by Charles Sneider in his presidential address to the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1905.22

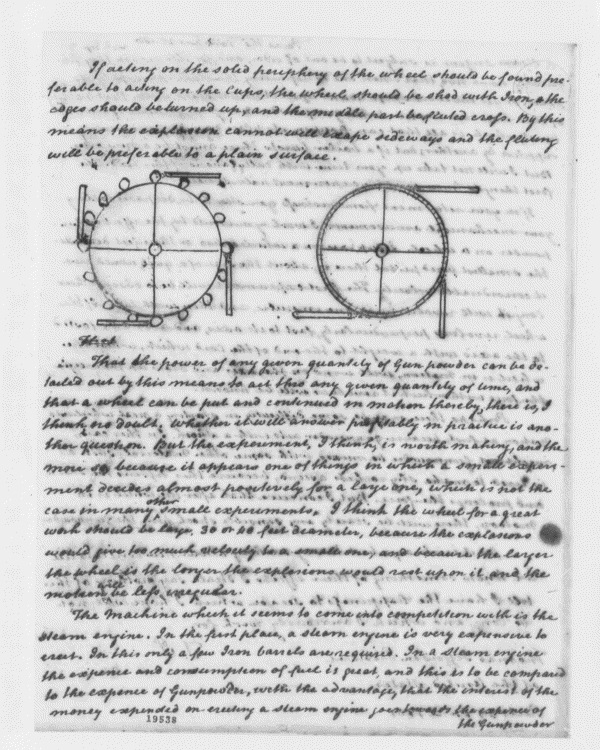

Paine’s tendency to emphasise the practical aspects of science is well illustrated by his bridge proposals. It is also shown in a letter he wrote to Thomas Jefferson on June 25, 1801. In this he proposed gunpowder as a means to drive an engine. Fortunately Paine does not appear to have attempted to put his speculations on this into practice. He had proposed this idea as he believed that steam engines were too heavy to be used as a form of transport but recognised the need for such a vehicle. Paine was wrong about the potential development of steam engines, but he probably had in mind the great beam engines then used in mines.23

Another idea Paine came up with was considered later to be a practical proposition and went into production. This was his invention of what he claimed to be a smokeless candle, about which he wrote enthusiastically to Benjamin Franklin, who had been a candle maker, and so, Paine presumably thought, better able to recognise the value of his invention. In his biography of Paine, D.F. Hawke wrongly refers to the invention as having exited no commercial interest.24 But he is wrong, for Paine’s smokeless candles were manufactured and sold throughout both Britain and the United States. The late Joseph Lewis possessed examples complete with a label which mentioned Paine as the inventor he had purchased in New York. The late Ernest Smedley of Hucknall, Nottinghamshire, still owned packets of ‘Thomas Paine’s Smokeless Candles’ which he had sold as an out-of-work miner from a marker stall in the 1920s. Whether the candles lived up to Paine’s claims, though, is another matter. According to his design the smoke was supposed to be carried downwards by holes in them to emerge at the base, but when W.E. Woodward had some made to Paine’s specifications he discovered they performed no better than normal candles.25

Astronomy appears to have been of considerable interest to Paine, as readers of his works will be aware. But there is reason to feel his active interest diminished during the Rights of Man controversy for he fails to take note of important discoveries about which he could have commented, particularly as one, a means of more accurately determining the distances he could have used in 1772. He is also silent about William Herschell’s discovery of Uranus in 1781.26 Although he possessed two globes there is no evidence for Paine having owned that most essential of astronomical instruments, a telescope. Paine’s interest in astronomy, then, would seem to have evolved basically into a theoretical approach which was more concerned with the theological and philosophical implications inherent in the subject than an interest in astronomy for its own sake. Of course it could be that when he attended science lectures in either 1767, as Conway claims, or 1757 as Thomas ‘Clio’ Rickman, a close personal friend of Paine from his Lewes days, maintained, but which Daniels in his study of Paine’s astronomy leaves open, showing there to be grounds for both dates being acceptable,27 he might have acquired a telescope but omitted to mention the fact. Daniels, though, feels Paine did not have had the money necessary to buy such an instrument. Paine subscribed to the notion of there being many inhabited worlds, this belief was not original to him and he may have first picked it up from reading Emmanuel Swedenborg, however, he was certainly one of the first to argue that scientists had been persecuted because of christianity, writing that had `Newton or Descartes lived three or four hundred years ago and pursued their studies as they did, it is most probable they would not have lived to finish them; and had Franklin drawn lightning from the clouds at the same time, it would have been at the hazard of expiring for it in the flames’.28 Protestant divines had condemned the Roman Catholic sect for persecuting scientists such as Galileo, but they did so from their standpoint of Roman Catholicism being a form of paganism not christianity. Paine did not make the distinction between the two traditions.

One wonders what Paine would have made of the theory of evolution. He offers no hints of having come across the idea, even though Erasmus Darwin’s controversial poetic work, Zoonomia, with its clear evolutionary message was published in 1794 and had been widely circulated. It may be that presented with the arguments for evolution Paine would have modified or even abandoned his creationism, as Ken Gregg suggests might be the case.29

In essence Thomas Paine is perhaps best described in so far as science is concerned as an inspired dabbler, except where his ideas on the use of iron for bridges is concerned. Here he has established himself to have been an outstanding pioneer who clearly appreciated its potentialities. He told his readers that the natural bent of his mind was towards science, but despite this his work took him in other directions. Be this as it may, there is no dispute about science having influenced Paine’s political and religious thinking. One cannot help wondering to what extent Paine would have made a name for himself as a scientist, or scientific writer, had he remained in the new United States rather than returning to Europe after the War of Independence to become involved in further revolutionary politics.

References

1. Williamson, Audrey. Thomas Paine, His Life, Work and Times. London, 1973. p.62, while John Keane credits the introduction to James Ferguson (Tom Paine, A Political Life. Bloomsbury, London, 1995. p.61). Probably both men were involved.

2. Paine, T. The Age of Reason. in The Life and Major Writings of Thomas Paine. Ed. P.S. Foner. Secaucus, 1974. p.500. Hereafter, Paine, Foner edn., which contains Paine’s major works.

3. Williamson. ibid. p.63.

4. Paine, Foner edn. p.496.

5. For a discussion see G.Hindmarch’s paper, ‘Thomas Paine: The Methodist. 23 Influence’. TPS Bulletin. 6.3.1979. pp.59-78.

6. Paine refers to himself as a christian in Crisis Paper No.7.

7. Paine, Foner edn. p.482.

8. Ibid. p.487.

9. Watson, R. Two Apologies, One for Christianity…Addressed to Edward Gibbon, The Other for The Bible in Answer to Thomas Paine. London, 1818. p.379.

10. Paine, Foner edn. p.946.

11. Daniels, R.G. ‘Thomas Paine’s Astronomy. TPS Bulletin. 1975. 2.5.pp.29-31.

12. Paine, Foner edn. p.496.

13. Daniels. op.cit.

14. It is reprinted in Moncure Conway’s edition of The Writings of Thomas Paine, 1774-1779. Putnam, 1894. pp.20-25

15. Edwards, W.N. The Early History of Palaeontology. London, 1967. p.40.

16. Conway omits the description in his reprint of the essay.

17. This was republished in New York by Hafner in 1964.

18. Paine. Foner edn. p.108.

19. Germer, R. The Secrets of Mummies’. Minerva. 8.1.1997. pp.53-55. 20. Daniels, R.G. ‘Thomas Paine on Yellow Fever’. TPS Bulletin. 1971.2.4.

21. Miller, S.T. ‘The Second Iron Bridge’. TPS Bulletin. 1996. 2.3.

22. Williamson. op.cit. p.106.

23. Conway, M.C. Ed. The Writings of Thomas Paine. Vol.4. pp.438-439. London, 1896.

24. Hawke, D.F. Paine. NY., 1974. p.163.

25. Woodward, W.E. America’s Godfather. London, 1945. p.157.

26. Daniels, R.G. ‘Thomas Paine’s Astronomy’. TPS Bulletin. 2.5.1975.

27. Daniels. ibid. p.31.

28. Paine. Foner edn. p.494.

29. Gregg, K. ‘Thomas Paine and the Rise of Atheism’. The American Rationalist. 31.5.1987.