By Derek Bailey

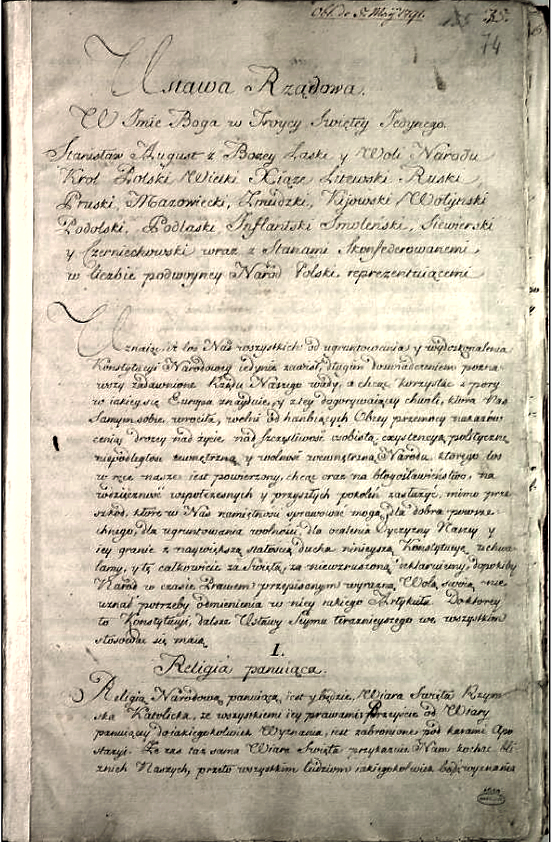

The constitution of May 3, 1791, is held in high regard by the generality of Polish commentators. Its mention in conjunction with the near contemporary United States Constitution and the French Constitution is not unusual. ‘The May 3rd Constitution provided, on the basis of the ideas of the French revolution, for the introduction of fundamental changes in the system of Poland’ (Arnold & Zychowski, 1962. p. 73).

From 1765 to 1795 was a period of Polish national renewal, affected by the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment. Both Rousseau’s Contrat Social and Montesquieu’s l’Esprit des Lois excited interest, and continuing contacts with France led in 1772 to the publication of Rousseau’s, Considerations sur le Gouvernement de Pologne.

A year later, in 1773, there was established the Educational Commission, taking control of nearly all schools in Poland. The schools were reorganised and the curricula modernised, Polish becoming the language of instruction. The revival of the Polish language contributed to the awakening of independent thought and the strengthening of a sense of Polish identity. Earlier education had been monopolised by the Jesuits, teaching being conducted in Latin.

It is possible that the observation on Poland in Rights of Man Part 2, that ‘it is only the government that has made a voluntary essay, though a small one, to reform the condition of the country’ (p.227) may have been a reference to reform accomplished and not reform in prospect. That is, to educational reform.

A few pages later, Paine observes, ‘Various forms of government have affected to style themselves a republic. Poland calls itself a republic…’ (pp.23-4). Paine’s judgement is unequivocal. ‘But the government of America, which is wholly on the system of representation, is the only real republic in character and in practice, that now exists’ (p.231).

Thus there are self-styled republics and real republics. Just so with constitutions.

The May 3 Constitution was adopted towards the close of the period of Polish national renewal.

Thomas Paine was known to Polish exiles, both in the United States and in France. Therefore it is natural to enquire, as does Libiszowsk (1998), what may have been the attitude of Paine to the occurrences in Poland. However, Thomas Paine was a practical man of public affairs and his attitude to the Polish Constitution may have been more circumspect than as suggested by Libiszowsk.

The process of constitution making and the content of the constitution may be considered separately. It is not known, with reasonable certainty, what Paine knew of either the one or the other concerning Poland. What his views may have been, had he been well informed, could be inferred, at least tentatively, from his known views in other contexts.

The constitution was prepared in secrecy (Zamoyski, 1992. p.348). The secret preparatory work was undertaken by the Polish king, Stanislaw Augustus, and a small group of advisers. Most shared a common interest in freemasonry (Gieysztor, 1968. p.351).

‘It was expected the project, with its eleven articles, would be approved by the Diet without discussion’ (Reddaway, 1971. p.135). ‘The events of 3 May 1791 were carefully staged… by circumventing normal procedure the draft law was read and voted at the same session’ (Gieysztor. p.374). That is, it amounted to a coup d’etat (Gieysztor. p.372).

Paine was emphatic that both enquiry into the nature of reform, and the undertaking of the reform decided upon, were not to be entrusted to a parliament or a government (pp.374-5). Sovereignty resided in the nation and it was for the nation to construct its own constitution. ‘A constitution is a thing antecedent to a government, and a government is only the creature of a constitution’ (p.122). ‘The constitution of a country is not the act of its government’ (p.122).

The proper approach, for the expression of the general will of the nation, was through the election of a National Convention so that ‘the nation will decree its own reform’ (p.376).

It was not how matters proceeded in Poland.

Prior to the adoption of the constitution, in December 1789, representatives of the towns had petitioned against their exclusion from the constitutional life of the country (Davies, 1982. p.354).

Concerning petitions, Paine was dismissive: ‘As to petitions from the unrepresentative part, they are not to be looked for’ (p.371). What did the eleven articles of the Polish constitution contain (Perhaps surprisingly, an English language text of the complete constitution, presuming one to be extant, has escaped detection)? The first article, while permitting the toleration of other faiths, confirmed that apostasy from the national faith of Roman Catholicism was not to be countenanced (Reddaway. p.147).

Thomas Paine, a deist, considered that each person should be free to commend himself to God in his own fashion, unconstrained by institutionalised religion. For Paine, ‘Toleration is not the opposite of Intolerance, but is the counterfeit of it. Both are despotisms’ (p.137).

`The estates are preserved, and the gentry were to possess their old privileges. The peasantry… did not obtain political rights (Reddaway. p.135).

Paine regarded the landed interest as, in effect, a conspiracy against the general interest (e.g. showing how in Britain their tax burden had been lightened to the disadvantage of the general population (p.277).

Enfranchisement was confined effectively to those possessing property. There were ‘tens of thousands of landless szlachta (Szlachta were members of a caste like nobility) who lost their vote overnight’ (Zamoyski, 1992. p.349). – For Paine, ‘it is dangerous and impolitic, sometimes ridiculous, and always unjust, to make property the criterion of the right of voting’ (p.397).

The Polish king, Stanislaw Augustus, ‘a confirmed bachelor’, was to be succeeded by the Saxon dynasty. ‘Frederick Augustus, Elector of Saxony… was invited to start the dynasty, and since he had no son yet, his daughter was designated the Infanta of Poland’ (Zamoyski, 1992. p.241). That is, the throne was to be ‘dynastically elective’ (Zamoyski, 1987. p.248).

Paine disapproved of monarchy, although not necessarily of the person of the monarch (p.97). For Paine, ‘To connect representation with what is called monarchy is eccentric government’ (p.233).

There is a further consideration.

`In all the volumes expended by Polish historians on the period 1788-94 very few words are wasted to explain that none of the splendid constitutional and social projects of the reformers were ever put into effect. Neither the Constitution of 3 May… were ever implemented’ (Davies, p.530).

And Paine? He set his face firmly against theoretical formulations. ‘A constitution is not a thing in name only, but in fact’ (p.122). The Polish king ‘did not take advantage of the extensive powers the constitution gave him in order to push through the revolution implicit in it’ (Zamoyski, 1992. p.347). There were practical reasons for not doing so. `Polish historians have tended to assume the country was united in its support for the constitution… This is retrospective wishful thinking based on the memoirs of leading Patriots’ (Zamoyski, 1992. p.348). The adoption of the 3 May Constitution was controversial within Poland. In fact, soon after the first anniversary of its adoption the 3 May 6 Thomas Paine Society Bulletin Constitution was rescinded. ‘In 1794 all laws passed between 1788 and 1792 were cancelled’ (Zamoyski, 1992. p.408), the Polish king throwing his lot in with the Confederation of Targowica (a group of nobles opposed to the reform process), the latter supported by Catherine the Great (an autocrat presumed to be sympathetic to the new currents of the Enlightenment) and Russian soldiery.

In 1795 the Third Partition led to the disappearance of Poland from the map of Europe for over one hundred and twenty years. And `England’s acquiescence’ (Libiszowsk. p.13). The beheading of ten leading burghers of the town of Torun in 1724, merely for being Protestant, had shocked non-Catholic Europe.

Writing in that year of 1795, Paine observed, ‘In all the countries of Europe (except in France) the same forms and systems that were erected in the remote ages of ignorance, still continue’ (p.387).

Bibliography

- Arnold, S. and Zychowski, M. Outline History of Poland. Warsaw, Polonia, 1962. Davies, N. God’s Playgrcnind: A History of Poland. Vol.1 . New York, Columbia U.P., 1982.

- Dyboski, R. Outlines of PolishHistory Westport, Greenwood, 1925/1979.

- Gieysztor, A. et.al. History of Poland Warsaw, PWN., 1968.

- Halecki, 0. A History of Poland London, Routledge and Regan Paul, 1978.

- Libiszowsk, Z. ‘Thomas Paine and the Polish Revolution’. TPS Bulletin. Vol.4. No. 1. 1998. pp.13-16.

- Paine, Thomas. Rights of Man, Common Sense and Other Political Writings OUP., 1955 (all quotations cited come from this edition).

- Reddaway, W.F. et.al. eds. The Cambridge History of Poland. New York,

- Octagon, 1971. Topolski, J. An Outline History of Poland Warsaw, Interpress, 1986.

- Zamoyski, A. The Polish Way. London, Murray, 1987.

- Zamoyski. A. The Last King of Poland London, Cape, 1992.