By Robert Morrell

Crisis Of Doubt, Honest Faith In Nineteenth-Century England. Timothy Larsen. 317pp. Hardback. OUP., 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-9287871. £60.00

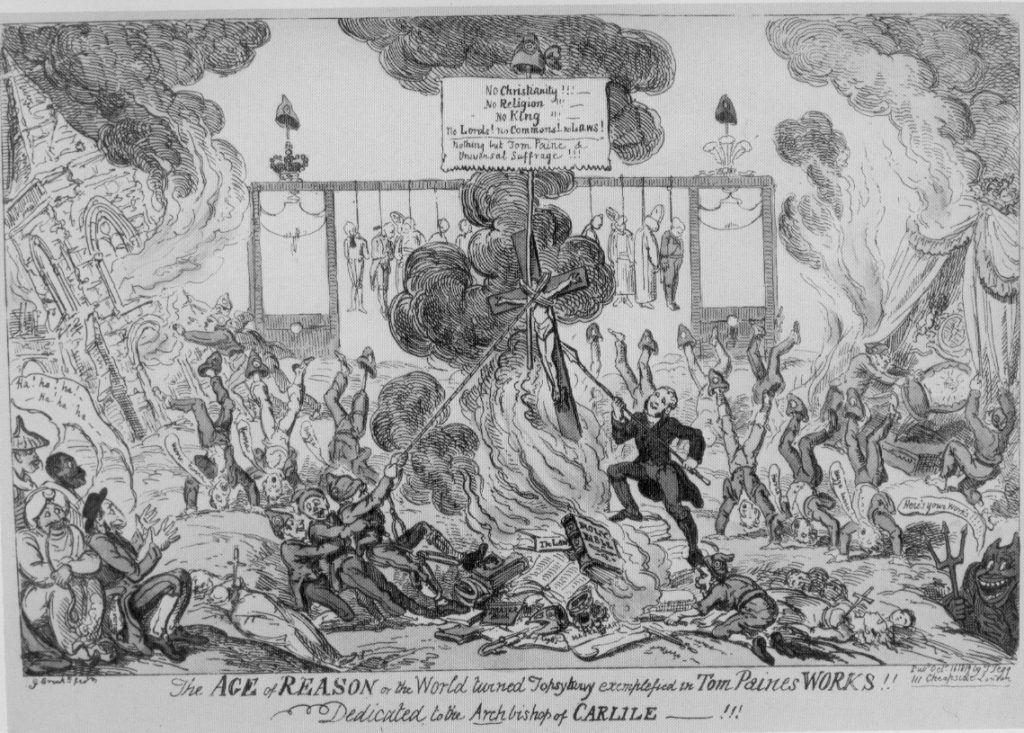

Although this is not a book about Thomas Paine, it does bring out the extent of his influence amongst members of the freethought and Secularist movement in England during the 19th century, in particular the use by them of the arguments found in his Age of Reason. However, this is incidental to the theme of the book, which is intended to demonstrate that the impact of unbelief amongst the populace was not as strong as most scholars contend. In addition, the author seeks to show that the intellectual integrity of Christianity successfully weathered the battering it had taken over the century.

Central to the author’s case is the story of seven individuals whom he puts forward as having been leaders of the freethought movement in England, which none were, although they were with one exception prominent speakers, these were William Hone, Frederick Young, Thomas Cooper, John Gordon, John Bebbington and George Sexton. The exception is Hone who was never an active freethinker or member of any specific freethought organisation, or, for the matter a genuine unbeliever as opposed to a dabbler. In Cooper there is considerable doubt as to whether he ever gave up belief in the first place, an uncertainty reflected in what Timothy Larsen writes about him.

Each of those named have a chapter in the book, described as “intellectual biographies”, devoted to them, but the presentation of the material is in my opinion marred too often by the author’s all too evident bias, which is understandable as he is a professional theologian whose job is to defend the belief system he subscribes to. His bias is all too evident in, for example, his remarks about a two night debate between G. W. Foote and Sexton at Batley held in Batley in 1877 on the theme of “Is Secularism the True Gospel for Mankind?” Sexton had been an able Secularist propagandist, even if he awarded himself self-created university degrees, and had at one time given an address praising Thomas Paine, though after his defection to Christianity he had little good to say of Paine. Larsen devotes a page to Sexton’s contribution to the debate in contrast to a mere two lines to that of Foote, thereby creating the impression that Sexton had come out on top, whereas anyone who actually reads the published transcript of the debate may well conclude otherwise and feel that in reality Foote had “wiped the floor” with his opponent.

Supplementing the biographical chapters is an appendix featuring a further twenty-nine individuals which carries the heading “More Reconverts and Other Persons of Interest”. The author states by way of explanation that many of those he includes are there simply because he finds them to be persons of interest in various ways and he is not claiming all as being reconverts, nor should their inclusion be taken as an attempt on his part to co-opt them. Amongst these “persons of interest” can be found Annie Besant, Richard Carlile, Keir Hardy, Robert Owen, George Romans and A. it Wallace. Larsen writes that space limitation imposed on him by his publisher forced him to exclude several others, although in a chapter entitled “How Many Reconverts?”, he holds out to his readers the prospect of further research revealing many more.

That the freethinkers managed to achieve as much as they did considering the odds against them is remarkable. But they could be their own worst enemy for in demonstrating that religion was of no real value in the day to day struggle for existence they caused many not simply to abandon it altogether, but to desert freethought for politics. That was the real end product of the conflict, indifference to the arguments of both sides. Nevertheless, if Crisis of Doubt can be said to have any real value it is to draw attention to a fascinating part of the nation’s social history.