By Derek Kinrade

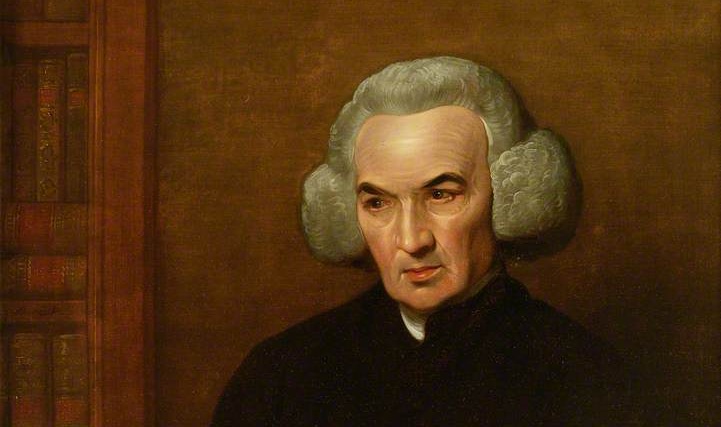

Dr Richard Price was a man of many parts: preacher, moral philosopher, commentator on actuarial and public finance, and ardent campaigner for civil liberties. This essay focuses, for the most part, on his latter activities.

One of the most influential radical thinkers of his day, though now little known beyond dedicated historians and scarcely quoted, he was a dissenting (non conformist) minister, the son of a dissenting minister, yet thoroughly traditional in his core beliefs in the omnipotence of God, the power of prayer and the rewards of heaven. Brought up and educated in the dissenting tradition, he cut no imposing figure, yet eventually attracted both a worshipful following as well as a coterie of powerful detractors.

He was dissenting, of course, as a Protestant refusing to accept the practice of the established Church of England, and therefore restricted under the harsh laws introduced after the collapse of the Puritan Revolution. The Toleration Act of 1689 provided some easement, but this had excluded Roman Catholics and Unitarians (a word that first appeared in Britain in 1673). Nevertheless, after 1774, Price followed Joseph Priestley and Theophilus Lindsey in avowing a revealed Unitarian theology based on reason and the enlightened conscience. Typically, beliefs were not precisely prescribed, but the emerging Unitarians rejected the doctrine of the Trinity (looking at God as One as distinct from Father, Son and Holy Spirit), the idea of original sin and the threat of eternal punishment (yet fell short of a rational rejection of theism). They held Jesus Christ in the highest regard, but as a mortal man, not an incarnate deity.

Newington Green

Unsurprisingly, some of those of this dissenting persuasion extended their nonconformity into areas of political criticism, with a zeal for social reform. Price was a remarkable example. Born in 1723, and ordained at the age of 21, he spent the first twelve years of his ministry as chaplain to the Streatfield family of London’s Stoke Newington, as well as assisting at the Old Jewry Presbyterian Chapel, before moving, with his new Anglican wife Sarah, to the village of Newington Green as minister of its nonconformist church in 1758. The house where they lived, 54 Newington Green, part of a surviving historic terrace, was next door to the banker Thomas Rogers and therefore, from 1763, to a baby, Samuel Rogers, destined to become one of England’s leading poets. The area was already established as a centre of non-conformity, home to many well-heeled dissenting families. During the next 30 years no.54 was to extend a welcome to a wide assortment of celebrities, including his close friends Benjamin Franklin, James Burgh (who kept a dissenting academy on Newington Green) and Priestley, along with occasional visitors such as David Hume and Adam Smith, John Howard, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, John Home Tooke, Lord Lyttleton, and Earl Stanhope. Allardyce (see sources) describes it as “an important meeting place for the progressive and radical thinkers of the day”.

By all accounts Price was not at first a great preacher. Cone (see sources) tells us that “his weak, unpleasant voice accentuated his other shortcomings as a speaker”, but that he later gained success “out of the thoughtful content of his sermons, the quiet earnestness of his demeanour, and his sincerity and humility”. These were virtues that were also effective in his writings. At least until his final address he was no firebrand; persuasive rather than dogmatic; indeed it was the mildness of his approach and his scholarly, measured discourse which earned respect from his friends and did much to confound those who opposed his views. His first important work was published in 1758 with a forbidding title which I will shorten to A Review of the Principal Questions and Difficulties in Morals. He had perfected this over many years, emphatic that morality should not be divorced from religion. Nature was evidence of God’s power and he believed that inconsistencies in such evidence were merely attributable to our inability to comprehend God’s design. This is not the place for a detailed analysis of a text running to nearly 500 pages, but it is relevant to bring out his insistence that intelligence is one of the requisites of practical morality, “necessary to the perception of moral good and evil”. And that liberty is essential to intelligent morality: “A thinking, designing, reasoning being, without liberty, without any inward, spontaneous, active, self-directing principle” cannot be conceived (pp 305-6). Thus, he argued, liberty and reason constitute the capacity of virtue.

A call to civil liberty

This passionate advocacy of personal freedom lay at the heart of Price’s thinking and found its most positive expression in his Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, published in February 1776 (compare Burgh’s Political Disquisitions (1774)). Here he sets out his concept of liberty as the principle of self-direction or self-government, in contrast to the external conquest of will and private judgement: the difference between freedom and slavery. “To be free,” wrote Price, “is to be guided by one’s own will, and to be guided by the will of another is the characteristic of servitude.” Liberty could be physical, moral or religious, but in relation to civil liberty, it was necessary for governance to be seen as “the creature of the people”, originating with them and conducted under their direction, with a single-minded view to their happiness. Thus taxes must be freely given for public services and laws established by common consent; magistrates being merely trustees or deputies for carrying regulations into execution. Price recognised that not everyone could express their views on public measures individually or personally, but they could delegate authority through the appointment of substitutes or representatives. In doing so, he stressed the importance of a rule that people given the trust of government should hold office only for short terms, chosen by the majority of the state and subject to their instructions.

Inevitably, he noticed, the interests of states would clash, but it would be no solution to make one of them supreme over the rest. His solution has a familiar ring: “Let every state, with respect to all its internal concerns, be continued independent of all the rest, and let a general confederacy be formed by the appointment of a senate consisting of representatives from all the different states.”

The antithesis of civil liberty, Price contended, was the doctrine that there are certain men who possess in themselves, independently of the will of the people, a God-given right of governing them. Such a view represented mankind as a body of vassals: “to be obliged, from our birth, to look up to a creature no better than ourselves as the master of our fortunes, and to receive his will as our law — what can be more humiliating? …There is nothing that requires to be watched more than power. There is nothing that ought to be opposed with a more determined resolution than its encroachment… should any events ever arise that should render the same opposition necessary that took place in the times of King Charles the first, and James the second, I am afraid that all that is valuable to us would be lost. The terror of the standing army, the danger of the public funds, and the all- corrupting influence of the treasury, would deaden ail zeal and produce general acquiescence and servility.”

The case for American independence

It is irresistible not to see the first part of the pamphlet as a prelude — a setting of the scene — for the slightly better-known Part Two, devoted to Price’s observations on the justice and policy of the war with America. He was overtly sympathetic to the cause of the American colonies, in which he had taken a close interest for some years, not least as a consequence of his friendship with Franklin. Stanley Weintraub (see sources) notices that in January 1774, Price, Edmund Burke and Joseph Priestley were among those in the gallery of the Whitehall Palace Cockpit when the 68- year-old Franklin was called to the Privy Council to answer a claim that he had “publicly exposed” private letters from the royal governor of Massachusetts that somewhat exposed the realities of British foreign policy. These, said to have been sent by Franklin in confidence to an old friend in Boston, had subsequently been leaked to the Boston Gazette. Though subjected to a long and vitriolic assault, Franklin made no concession, but was eventually stripped of his representative office and obliged to return to America. The humiliation merely served to raise Franklin’s reputation in his home country and to reinforce a divide that was on its way to becoming irreconcilable.

Both Price and Franklin had been members of the ‘Honest Whigs Club’ from at least 1769, along with James Boswell, dissenting clergymen Joseph Priestley and Andrew Kippis, James Burgh, botanist Peter Collinson, and Sir John Pringle (from 1772-78 president of the Royal Society – to which Price had himself been elected in 1765). The club met in a coffee-house on alternate Thursdays, and whilst we cannot now be privy to their discussions it seems clear that for some of them radical political reform was high on the agenda. They must have fed off each other, for obvious similarities are evident in the writings of Franklin, Burgh, Priestley and Price.

Up to mid-1775, despite military activities, the grain of popular sentiment in America and the perceived colonial objective had generally been one of reconciliation. There was trust in George III and a belief that the British parliament would see sense and be persuaded to restore American rights within an amicable union. Indeed there was a view, especially in the so-called Continental Congress, that independence would not only be disloyal but might lead to mob rule and the loss of relatively safe trading routes. Such faith in the monarchy was, however, soon to be dispelled by a series of repressive royal measures and pronouncements which clearly demonstrated that the king was leading rather than being overruled by parliament, and was deaf to colonial supplications for conciliation and reform. Price had by this time been increasingly drawn into the political arena, both in his campaigning against the continuing intrusion upon the rights of Protestant dissenters and his empathy with the colonial rebellion. His contacts in London and letters from America kept him in touch with the tide of events across the Atlantic and elicited his unequivocal support for the rebels and their cause. There had been little appetite for war among the general populace in Britain, and several prominent people had warned of the futility of attempting to subdue the aspirations of these distant and disparate colonies by military force. But the king and his establishment were fixed on a collision course of crushing the rebellion, maintaining control, order, obedience and the sovereignty of parliament: effectively domination. Towards the end of 1775, Price determined to enunciate his thinking. When his Observations were published on 9 February 1776, six years had elapsed since the Boston ‘massacre’, all but nine months since the attack at Lexington and, crucially, more than a month after the sensational appearance of Paine’s Common Sense (some three months if one takes account of the time needed for Price’s pamphlet to reach America). It is now apparent to us that, although Price’s text reinforced the bid for independence and was welcomed, the American Congress was already moving to a separation from Britain: the die was already cast and the rift beyond reconciliation.

Yet Price’s work contains some imperishable principles which have since been tested by history and deserve our closer attention. Typically, he began with a barbed olive branch, ready to make great allowances for the different judgments of others, rhetorically conceding that his words would not have any effect on those who still thought that British claims could be reconciled to the principles of true liberty and legitimate government. He recognised that the idea of America as a subordinate British colony was deeply ingrained, but argued that this was open to a change of heart when the idea of colonists being British subjects, bound by British laws, was seen to be unreasonable when tried against the principles of civil liberty.

He pointed out that, although novel, the fact that the colonised state was on its way to becoming superior to its parent state was something that should be considered on the ground of reason and justice, rather than the old rules of narrow and partial policy. Alas, however, he saw that matters had already gone too far and that conflict (“the sword”) was now to determine the rights of Britain and America. But he thought it was not too late to retreat; to rely on the king’s disposition to “stay the sword”.

First, one should consider the justice of the war. This rested upon an act of parliament giving Britain the power and the right to “make laws and statutes to bind the colonies and the people of America, in all cases whatever”. A dreadful power indeed, commented Price: “I defy anyone to express slavery in stronger language.” It amounted to saying that we had a right to do with them what we please.

Price rejected the argument that there needed to be a supreme right to interfere in the internal legislations of the colonies, “in order to preserve the unity of the British Empire”. He pointed out that similar pleas had, in all ages, been used to justify tyranny, citing the example of the Pope as head of the Roman Catholic Church. Such an approach could produce “nothing but discord and mischief’.

Nor could it be claimed that Britain was the superior state as the parent state. Parents do indeed have authority over their children, but only until they become independent and capable of judging for themselves. Thereafter only respect and influence is due to the parent. By this measure our authority in relation to the colonies should have been relaxed as they “grew up”, whereas we had taken our authority “to the greatest extent, and exercised it with the greatest rigour… No wonder then, that they had turned upon us.” The land was not ours simply because we had first settled there; if anyone could lay such a claim it was first with the natives, and then only with the settlers who cleared and cultivated the wilderness. Had they not, he asked, then established a system of governance similar to our own, with our agreement, for more than a century? Was it any wonder that they should revolt when they found their charters violated, and an attempt made to force innovations upon them by famine and the sword?”

But aside from charters, Price continued, was it common sense to imagine that when people settle in a distant country those they have left behind should for ever be able to control their property and have the power to subject them to any modes of government they please? To be taxed and ruled by a parliament that does not represent them? And ought we to be angry because the colonies looked for a better constitution and more liberty than that enjoyed in Britain? Rather should it not be wished that there may be at least one free country left on earth to which we might flee when venality, luxury and vice had completed the ruin of liberty here? Imposing taxes without representation, Price suggested, was simply another form of despotism.

Price then turned to the future, with, we can now judge, top marks for foresight. If, he speculated, it was argued that Britain had a supremacy entitling its government to exercise jurisdiction over taxation and internal legislation, should we then be equally entitled in perpetuity? In 1775 the colonists numbered a little short of half the British population, but the probability was that in another 50 or 60 years they would double our numbers, forming a mighty empire, consisting of a variety of states with the same or greater accomplishments and arts “that give dignity and happiness to human life”. Would they then have to continue to acknowledge Britain’s claim to supremacy, even should our legislature degenerate into a body of sycophants, little more than a public court for registering royal edicts?

These were powerful arguments in favour of self-determination for the American colonies, reinforced by a scarcely concealed scepticism about our own governance and its future. Price went on to discuss specific aspects of the war with America: whether it was justified by the principles of the British constitution, its policy implications, its effect on the honour of the nation and the probability of its success. In its belief that discontent could be quelled by a resort to force of arms, he argued, the government had massively over-reacted, provoking a shift away from a natural disposition to accept British authority and co-operate in trade to a general exasperation and spirit of revolt.

Divergent reactions

In Britain, Price’s Observations prompted considerable interest: predictably divided between liberals who generally shared his views and conservative opponents who quickly published a number of angry rebuttals; not least one from John Wesley, who saw Price’s work as “a dangerous Tract…which, if practised, would overturn all government, and bring in universal anarchy.” But apart from concern raised by his close analysis of the likely financial consequences of war, Price’s text had little effect; none at all on Britain’s belligerent foreign policy. There were some fears for Price’s safety, but in fact no punitive action was taken against him. Ambrose Serie, the secretary to the British Admiral Lord Richard Howe, saw it as evidence of the mildest & most relaxed Government in the World”. In any other state than Great Britain, he argued, the book would have been burned and the author hanged.

In America, unsurprisingly, Price’s text was well received and added to the author’s already glowing reputation. But whereas Paine’s Common Sense made a forceful and unambiguous case for independence and transformed colonial opinion, I think that the response to Price was no more than thoughtful. I think that anyone who reads Price’s full text, as against my considerable simplification (indeed over simplification) cannot fail to be struck by the contrast between Paine’s plain speaking and concise, straightforward and inspirational prose and Price’s lengthy perambulations. This distinction, I believe, similarly accounts for Price’s relatively low-key historical reputation. This is unfortunate, because the essence of Price’s text is not dissimilar from the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, adopted only five months after the publication of Observations. Price’s thinking went to the heart of the values on civil liberty that we now share with the United States. Sagely, Cone titled his biography of Price Torchbearer of Freedom.

The Declaration itself, written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, further fermented the spirit of rebellion, particularly against the obdurate George III. After its famous opening statement of principle it enumerated the history of the king as one of “repeated Injuries and Usurpations”, all directed to the establishment of an absolute tyranny over the states of the Union, and concluded with a declaration that the united colonies were free and independent states absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown. Readings of the text were organised in various parts of the colonies, prompting demonstrations hostile to the British and its monarch, the most famous of which took place in the evening of 9 July 1776 in New York. When the reading was over, a crowd marched to the Bowling Green, the location of William Wilton’s splendid representation of a mounted George Ill. In a great symbolic gesture, the rebels pulled horse and monarch down from its plinth, an event which now inevitably draws comparison with the fate of Sadam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad. In the case of the unfortunate image of George, the insult was intensified when the statue was later melted down and made into musket balls: apart, that it, from its head, which was mounted on a pole and exhibited for a time outside Fort Washington.

Meanwhile, Price’s pamphlets continued to make waves at home. In the face of heavy criticism he went on to produce Additional Observations in 1777, and to republish a combination of both texts in 1778, attracting still more abuse. In America, by contrast, his popularity continued to grow. On 6 October in the same year, as a mark of the esteem in which he was held in America, Congress wrote to express its desire to consider him a citizen of the United States and to solicit his help in regulating their finances. He could be remunerated both for the move there and his services. But Price, no longer eager or feeling himself sufficiently fit for any such challenge, while gratified, graciously declined. Cone records that in his reply he looked to the United States as “the hope, and likely soon to become the refuge of mankind”. In 1781 Yale University honoured Price as a Doctor of Law, and in the following year the American Academy of Arts and Sciences awarded him a fellowship.

Nor was this the only political offer. Lord Shelburne, an old friend, keenly aware of Price’s financial expertise and concern for the national debt, had sought to tempt him away from his theological pursuits. When appointed Prime Minister in July 1782, on the death of Rockingham, he promptly asked Price to assist him. Once again, content in the radical milieu of Newington Green and preaching to a full chapel, Price declined, feigning that he did not have much to contribute. As it turned out, the opportunity would have been short-lived. Shelburne resigned in February 1873, after defeats in the Commons.

Strategies for a blessed peace

The end of the American war brought Price back into the political scene. He was able to correspond more freely with his friends in the new world, and soon started work on a pamphlet which reached the United States in 1784: Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution, and the means of making it a benefit to the world. Though his advice was unsolicited, it was warmly welcomed by Franklin, Jefferson, Adams and other friends, thankfully received by members of Congress (and by George Washington personally), and widely read and admired. He enjoyed a status as a champion of America and in January 1785 was elected into membership of the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia.

In these Observations, Price suggested that the American Revolution, next to the introduction of Christianity, might prove to be the most important step in the progressive course of human improvement: a casting off of the shackles of superstition and tyranny. At the end of the pamphlet he conceded that he may have carried his ideas too high and deceived himself with visionary expectations. But there are those who find parallels in Price’s Observations and the American Constitution of 1788, and a close reading of his remarkable text will certainly reveal some surprising and timeless principles.

Of particular interest are his thoughts on the “supreme importance” of religious and civil liberty, based on truth and reason. He looked for constitutional developments that would make government even friendlier to liberty, as a means of promoting human happiness and dignity; specifically liberty of discussion in all speculative matters and liberty of conscience in all religious matters, subject to restraint only if used to injure anyone in their person, property or good name. In the exercise of liberty of discussion Price included “the liberty of examining all public measures and the conduct of all public men; and of writing and publishing on all speculative and doctrinal points”.

Here Price faced a difficulty, for he was aware of a common opinion (then as now) that some matters were so sacred, and others of so bad a tendency, that no public discussion of them ought to be allowed, and that those in authority should penalise any such discussion. Those, for example, who opposed the Muslim view of the divine mission of Mohamed, the Popish view of worship of the Virgin Mary, or the traditional Protestant view of doctrines of the Trinity or the supreme divinity of Christ. But, argued Price, civil power had nothing to do with such matters, and was not equipped to judge their truth. Would not, he asked, perfect neutrality be the greatest blessing? Different sects were continually exclaiming against one another’s opinion as dangerous and licentious. Even Christianity, at first, was so accused in that it ran counter to pagan idolatry; and the Christian religion was therefore reckoned “a destructive and pernicious enthusiasm”. Were this kind of judgment the rule there would be no doctrine, however true or important, the avowal of which would not in some country or other be subjected to civil penalties.

Price next turned to liberty of conscience: freedom of religious belief and practice. Here he was on his home territory, and expounded — at length — on the virtues of true religion and their perversion when civil authority was involved. This, essentially, was a statement of the Unitarian position: a blast against slavish adherence to “obsolete creeds and absurdities”, imposing boundaries on human investigations and confining the exercise of reason. In some European countries, wrote Price, these dogmas and rituals had been recognised and acknowledged, but had become so entrenched by the state apparatus that it was scarcely possible to get rid of them. In his own country the growth of enlightenment had had no effect on the religious establishment: “not a ray of the increasing light had penetrated it”. Price believed that there were lessons here for America, where constitutional examples — while not perfect — encouraged him to think it might be possible that pernicious civil forms of gloomy and cruel superstitious religion might be avoided.

Price’s thoughts on education were similarly challenging. He believed that its purpose should be to teach how to think, rather that what to think. He particularly regretted that people of different faiths, convinced that they alone had discovered the truth, should be confident advocates of education; whereas the “very different and inconsistent accounts that they gave” demonstrated that they were utter strangers to the truth. It would be better to teach nothing, he suggested, than to teach what they held out as truth.

The greater their confidence, the greater the reason to distrust them: “We generally see the warmest zeal where the object of it is the greatest nonsense.” Thus, in Price’s view, education ought to be an initiation into candour, rather than into any systems of faith. Hitherto, education had been dominated by adherence to established and narrow [formulaic] plans, whereas Price contended that the mind should be rendered free and unfettered, quick in discerning evidence, and prepared to follow it from whatever quarter and in whatever manner it might offer itself.

There were other snares and dangers facing the emerging nation. Price ranged briefly over the need for a just settlement of federal union and the avoidance of internal conflict. He warned of the danger of disputes being settled at “the points of bayonets and the mouths of cannon”, instead of relying on the collective wisdom of confederation. He stressed — as he had begun – the perils associated with excessive public debt, and the importance of preventing too great an inequality in the distribution of property. He saw equality in society as essential to liberty and, in this regard, urged that America would do well to avoid the British enthusiasm for hereditary honours and titles of nobility. Let there be honours to encourage merit, he proposed, but let them die with those who had earned them rather than bequeath to posterity a proud and tyrannical aristocracy. America would be better off without lords, bishops and kings, and certainly without the rule of primogeniture.

Price similarly inveighed against excessive love of one’s own country, widely applauded as one of the noblest principles of human nature, but in fact one of its most destructive forces. He commended instead the benefits of communication across nations, whence people could see themselves as citizens of the world rather than of a particular state.

But Price saved his most fervent — and controversial — proposition to a final section headed ‘Of the negro trade and slavery’. He was not the first writer to point out that slavery was completely at odds with principles of equality. Benjamin Rush had castigated slavery as a national crime, and early in 1775 Thomas Paine had made a spirited attack against the trade in The Pennsylvania Journal. Price himself cited Thomas Day’s tract Fragment of an original Letter on the Slavery of the Negroes, written in 1776, but not published until 1784. Keane (see sources) refers to there having been around half a million slaves working in the 13 colonies during the Revolution. The system of forced labour was well established and widely seen as legitimate. Price would have none of this. The trade was one that ‘cannot be censured in language too severe”; a traffic “shocking to humanity, cruel, wicked and diabolical”. Until measures were introduced to abolish this odious servitude, the United States would not deserve the liberty for which they had fought. Three years later a certain William Wilberforce would be drawn into the abolitionist cause.

A female protege

In the year marked by the publication of his observations on the American Revolution, an accident of fate introduced a completely different interest into Price’s day job at Newington Green. A young woman, destined famously to assert the rights of women, took a lease on a large house within sight of the church. Mary Wollstonecraft, aged 25, had chanced upon an unexpected inspiration. It is not for this article to set out the complex circumstances that brought Mary, her dearest friend Fanny Blood and her sister Eliza to this part of London; suffice it to say that, led by Mary but lacking adequate resources, each of them was seeking to break out from miserable situations and equally breaking with convention. They remained for a relatively brief period that was in many respects an unhappy one, marked by an unending struggle to make ends meet, the death of Fanny, and the ultimate impracticability of making a success of the school. But it was also a precious time that brought Mary into contact with Price and his circle. Although an Anglican, Mary was also drawn to attend the dissenting church, and was invigorated to experience the support and stimulation of good people whose religion was based on reason rather than a belief in supernatural events. Here, among an assembly of intellectual radicals steeped in a tradition that went back to Defoe, she was exposed for the first time to radical ideas, to the quest for change, seen as a realistic possibility. Here she was introduced to Joseph Priestley and taken to Islington to meet Samuel Johnson (though she preferred the thinking of Price) and, through Price, met her future publisher Joseph Johnson. And she also met women who could hold their own. The dissident aspiration for social reform took Mary in a particular direction in keeping with her personal experience, as a female, of blatant discrimination. We may conjecture that it influenced her in writing her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, which earned her a much needed advance from Joseph Johnson. Her school survived only until the autumn of 1786, when she moved to Ireland, but her experience at Newington left an indelible impression. Tomalin (see sources) refers to a letter from Mary in which she mentioned the particular friendliness of Dr. Price. Though his wife was dying (Sarah passed away on 20 September 1786 after a long illness), he still had time to think of Mary’s welfare. Tomalin comments that Mary learnt a great deal from Price; although she was never tempted to exchange her “easy-going” Anglicanism for his dissenting faith, he “set her on certain paths and prepared her to think critically about society”.

Inspired by revolution

The loss of Sarah, advancing age and declining health bore down on Price. He relocated to Hackney and, though continuing to preach, was mindful of retirement. Events, however, were moving in the opposite direction. It is hard to say quite when discontent in France could fairly be called a revolution, but by 1789 the social upheaval there was recognised as a powerful movement that could easily spread abroad; in Britain bringing hope to radicals aching for reform and fear to those attached to the old social order. Price, despite his tribulations, was drawn into the fray. As a leading member of the London Revolution Society, the agitation in Paris excited him and other radical protagonists to think that what had been achieved in America might be transplanted into Europe and give power to the people. The Society had been formed in 1788 to commemorate the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, but inevitably interest was now centred more on the revolution in France. On 4 November 1789 (the anniversary of the birthday of William of Orange), at the annual meeting of the Society held in the Dissenters’ meeting house in Old Jewry, Price delivered a daring sermon, quickly published as A Discourse of the Love of Our Country (with various appendages). This, of course, was an opportunity to return to some of his most precious themes and stand conventional thinking on its head.

‘Country’ he said, was not to be thought of as the soil or spot of earth on which we happened to be born, but rather the community of which we were members. Nor should we see our country or its laws and governance as superior to other countries; nor confine wisdom and virtue to the circle of our own acquaintance and party. Indeed, we should see ourselves as citizens of the world guided by the blessings of truth [enlightenment], virtue and liberty, embracing under God universal benevolence, and loving our neighbours as ourselves. An enlightened and virtuous community must also be a free country; one that did not suffer invasions of its rights, or bend to tyrants. Obedience to just laws was essential to prevent a state of anarchy, but there were extremes of compliance that ought to be avoided: adulation was always odious and, when offered to men in power, served to corrupt them. Price deplored servility, and castigated the crawling homage that had greeted George ill’s recovery from illness. He would have chosen to wish that the king would henceforth more properly consider himself the servant than the sovereign of his people.

He asked his congregation not to forget the principles of the 1688 revolution, which the Society had held out as “an instruction to the public”, notably:

- the right to liberty of conscience in religious matters,

- the right to resist power when abused, and

- the right to choose our own governors; to cashier them for

- misconduct; and to frame a government for ourselves.

Price rejoiced that the ‘Glorious Revolution’, which had got rid of James II, had broken the fetters of despotism and saved Britain from the “infamy and misery” of popery and slavery. Yet, he was eager to point out that those events had fallen short of delivering perfect liberty. He lamented in particular continued civil restrictions on dissenters and the gross and palpable inequality of parliamentary representation. (in a footnote added to the version published in 1790 he defined this as “A representation chosen principally by the Treasury and a few thousand dregs of people who are generally paid for their votes.”) The state of the country was such as to render it “an object of care and anxiety”: a monstrous weight of debt was crippling it, and vice and venality were such that the spirit to which it owed its distinctive qualities was in decline. Every day seemed to indicate that the country was becoming more ready to accept encroachments on its liberties.

But again Price saved his most audacious salvo to the end of his address. He declared that he saw “the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priests giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience.” The times were auspicious. People were “starting from sleep, breaking their fetters, and claiming justice from their oppressors.” The spirit (“light”) that had set America free had reflected on France, and there kindled into a blaze that was laying despotism in ashes, warming and illuminating Europe! He concluded with a warning: “Tremble all ye oppressors of the world! Take warning all ye supporters of slavish governments and slavish hierarchies!…You cannot now hold the world in darkness. Struggle no longer against increasing light and liberality. Restore to mankind their rights; and consent to the correction of abuses, before they and you are destroyed together.”

On the same evening, members of the Society met again for their annual dinner at the London Tavern. Price, no doubt weary but still animated, moved an address to the National Assembly of France sending congratulations on the revolution and the prospect it gave “to the first two kingdoms in the world of a common participation in the blessings of civil and religious liberty”. As well as adding ardent wishes for the settlement of the revolution, the Society unambiguously and unanimously joined in expressing the particular satisfaction with which they reflected on “the tendency of the glorious example given in France to encourage other nations to assert the inalienable rights of mankind, and thereby to introduce a general reformation in the governments of Europe, and to make the world free and happy.”

A mixed response

The radical sermon and the congratulatory message inevitably reignited hostility to Price and provoked a pamphlet war. Price was not without supporters, yet perhaps the most telling reservation came not from an enemy but a valued friend. When John Adams, who was to become the second President of the United States, was appointed the new American minister to the Court of St. James in 1785, he and his family had travelled to Hackney to hear Price preach. But when, five years on, Adams read Price’s Old Jewry sermon, his response, while generous, was cautious. He warmed to its principles and sentiments, and recognised the historic importance of the French Revolution, but felt constrained to add that he had “learned by awful experience to rejoice with trembling.” He knew that France was not America, and warned that in revolutions “the most fiery spirits and flighty geniuses frequently obtained more influence than men of sense and judgment; and the weakest man may carry foolish measures in opposition to wise ones proposed by the ablest.” He saw France as being in great danger. McCullough (see sources) remarks that ahead of anyone in the government, and more clearly than any, Adams foresaw the French Revolution leading to chaos, horror, and ultimate tyranny.

Mary Wollstonecraft’s defence of his Discourse (A Vindication of the Rights of Men), published anonymously, was decidedly double- edged, arguing that while his final political opinions were “Utopian reveries” they deserved respect as the product of a benevolent mind tottering on the verge of the grave. The world, she argued, was not yet sufficiently civilised to adopt such a sublime system of morality.

Edmund Burke had been far less kind. As well as being alarmed by Price’s discourse he was also aware of Thomas Paine’s sympathy for the Revolution, and spent the best part of 1790 preparing his Reflections on the Revolution in France, published on 1 November. He wrote of his astonishment on discovering a Society that had devoted itself to consideration of the merits of the constitution of a foreign nation, leading on to sending, as though in a sort of public capacity, a sanction to the proceedings of the National Assembly in France; on its own authority and without the express agreement of the Society’s own government. He saw Price’s sermon as having been designed to connect the affairs of France with those of England, “by drawing us into an imitation of the conduct of the National Assembly”. This had given him “a considerable degree of uneasiness”. He had found “some good moral and religious sentiments, and not ill expressed, [but these were] mixed up in a sort of porridge of various political opinions and reflections”, of which the French Revolution was the “grand ingredient in the cauldron.”

Burke saw the congratulatory message sent to the National Assembly as a corollary of the principles of the sermon, moved by its preacher. Few harangues from the pulpit, he wrote, had ever breathed less of the spirit of moderation. Much as in our own time the Archbishop of Canterbury has been criticised for expressing his political dissent in the pages of the New Statesman, Burke observed that “no sound ought to be heard in church but the healing voice of Christian charity.” “The cause of civil liberty and civil government,” he argued, “gains as little as that of religion by this confusion of duties.”

Burke’s Reflections are well known and need no further elucidation here. The same can be said of Paine’s famous rejoinder. The first part of his Rights of Man was published on 13 March 1791_ Little more than a month later, on 19 April, Price died, having been for some months, as Cone puts it, “a silent spectator to events in France and England”. He was buried at Bunhill Fields, after a service led by Joseph Priestley. Allardyce tells us that the funeral route was so crowded by well-wishers that the coffin arrived five hours late for the service.

We, of course, have the benefit of hindsight in knowing that Britain would not take the revolutionary road. But it is important to understand that Price and Paine were writing before the onset of the horrific phase of the French Revolution that came to be known as the Reign of Terror. They believed that the uprising heralded a new dawn. Price knew that there were dangers. In a footnote to the Discourse he accepted that countries lacking our “excellent constitution of government” could not achieve liberty without “setting everything afloat, and making their escape from slavery through the dangers of anarchy.” But it is reasonable to surmise that the “good Dr Price” — known for freeing birds caught in the nets of local bird-catchers and a hero to poor people in Newington Green — would have shifted his ground in the light of those terrible events. The bloodletting in France (which almost claimed Paine’s life) need not be seen as invalidating Price’s cherished principles. It is perhaps rather that we British have been slower to act and less inclined to dramatic change and violence. Reform towards Price’s Utopia has gradually been conceded, both in Britain and the European Union, but has taken longer. Some may feel that even now we have still some way to go in achieving the goal of “perfect liberty”.

Sources

Carl B. Cone: Torchbearer of Freedom, the influence of Richard Prim on eighteenth century thought (University of Kentucky Press, 1952).

Richard Price: Observations on the nature of civil liberty, the principles of government and the justice and policy of the war with America (1776, available as a Google book).

Richard Price: Observations on the importance of the American Revolution, and the means of making it a benefit to the world (the edition of March 1785, available as a Google book).

Richard Price: A Discourse on the Love of Our Country (T.Cadell, 1790; available as a Google book).

Edmund Burke: Reflections on the Revolution in France, and on the proceedings in certain societies in London relative to that event (J. Dodsley, 2’d edition, 1790, available as a Google book).

Alex Aliardyce: The village that changed the world (Newington Green Action Group, 2”d ed. 2010).

Stanley Weintraub: Iron Tears, rebellion in America 1775-1783 (Simon & Schuster, 2005).

Gregory T. Edgar. Campaign of 1776 — the road to Trenton (Heritage Books, 1995). Contains a brilliant account of the close-run congressional debate on the Declaration of Independence.

United States Declaration of Independence (the first Dunlap broadside version, 4 July 1776).

David McCullough: John Adams Simon & Schuster, 2002).

Claire Tornalin: Mary Wollstonecraft (Penguin, revised edition 1992).

John Keane: Tom Paine, a political life (Bloomsbury, 1995), Mary Wollstonecraft: A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790).