By Richard Briles Moriarty

The dedication of Thomas Paine to rational thought and inquiry was unparalleled amongst the Founders.1 His commitment to a strictly rational regimen was particularly notable, and fraught, on the religious front.2

In Paine’s view, organized religions marketed unreliable hearsay piled on hearsay as “revelations” that are, by definition, based on faith rather than evidence.3 Carefully observing nature, he rejected nearly everything propounded by organized religions as antithetical to rational analysis, retaining from Biblical accounts only what was discernable through observation.4

Restricting his mental diet to reason did not make him an atheist. To the contrary, Paine concluded that “reason can discover” the “existence of God.” Articulating his thought process, Paine first observed that nothing can make itself. He then noted that many things do exist such that those things were undeniably made. Articulating his thought process, Paine first observed that nothing can make itself. He then noted that many things do exist and, therefore, were undeniably made. Rounding out that syllogism, Paine reasoned that there must be “a power superior to all those things, and that power is God.”5

Related declarations are more difficult to square with his allegiance to reason. Paine expressed absolute confidence that “Providence” actively intervened to protect not just America but Paine himself. By contrast to his express articulation of why, logically, existence of a Deity comported with reason, his surviving writings disclose no hint of a rationale for believing in an intervening Providence.6 More puzzling, when he referenced gender regarding Providence, he identified Providence as female, never as male. Like his expressed belief in an intervening Providence, those identifications appear in his writings as unexplained givens.7

Two separate but intertwined mysteries are implicated. How could Paine reconcile a belief in an intervening Providence with his dedication to rational inquiry? Why did Paine, uniquely among the Founders and other contemporaries, identify Providence as female? That both mysteries ultimately resist resolution should not surprise Paine aficionados given how much is unknowable regarding Paine, primarily due to an 1830s fire that consumed many of his papers.8 What may surprise is that, on the unknowable subject of Providence, Paine conveyed definitive conclusions with utter confidence and calmness and without any explanations, rational or otherwise.

Paine vigorously pursued rational inquiry as far as it would take him—farther than some contemporaries preferred—insisting that societal systems incapable of withstanding rational inquiry should be abandoned. But remarks about the limits of human capabilities and his persistent optimism in the face of frequent adversity suggest that, when faced with the inexplicable, Paine was neither frustrated nor sought to flog the inexplicable into submission.9

John Keats contended that creativity in people “of Achievement” is opened to new and fruitful frontiers by embracing “uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”10 Paine knew nothing about Keats, having died in 1809 when Keats was only thirteen. But conceivably Paine, despite or even because of his dedication to reason, would have appreciated this concept of “Negative Capability” developed by Keats in 1817.11

The boundary between the rational and the inexplicable is individual for each human and shifts over time and societal developments with no bright line demarking that boundary. With Keats applying his deeply probing mind to poetical expression, for example, while Paine applied his to clear and rational thinking and writing, they would have encountered dramatically differing locations. But when they each individually faced what they respectively deemed the inexplicable, it is conceivable that their responses may have paralleled.

Did Paine refrain, in those circumstances, from “irritable reaching after fact & reason”— with irritable being the key word— and, encouraging his sense of wonder to flourish, allow deeper and unexpected insights to come his way?12 If so, Paine may well have experienced, as Keats expressed elsewhere, “‘the intense pleasure of not knowing’” on those occasions when Paine’s pursuit of rational inquiry left significant questions unanswered and unknowable.13 Exploring the two mysteries posed here may provide keys to appreciating the complicated force that was Thomas Paine and, more generally, the limitations of rational inquiry and contemplation of the inexplicable that each human must address within their own mind.

INTERVENING PROVIDENCE AND RATIONAL INQUIRY

In America during the Revolutionary Era, belief in an intervening Providence was nearly universal.14 Contemporaries belonging to Calvinist sects, like Samuel Adams, John Jay and John Witherspoon, were certain that Providence as a manifestation of the male God intervening regularly in human affairs in ways that comported with Biblical texts, which were literally the Word of God.15 Deist Founders filtered their beliefs in an intervening Providence through rational inquiry.16 Because Paine was more obsessively dedicated to reason than other Deist Founders, his belief in an intervening Providence is notable.17 His assumption that Providence directly intervened to protect him personally was most explicitly expressed when, after returning to America, he lambasted Federalists for attacking him. He questioned why they didn’t also attack Providence for having protected Paine “in all his dangers, patronized him in all his undertaking, encouraged him in all his ways, and rewarded him at last by bringing him in safety and in health to the Promised Land.”18

Terrific satire and intentionally over-the-top. But could Paine reason his way to a belief that a supernatural force directly intervened to protect him, as an individual, from harm? Paine firmly rejected the concept of guardian angels, expressly criticizing Quaker pacifists in 1775 by declaring that “we live not in a world of angels” and that we cannot “expect to be defended by miracles.”19 His Age of Reason more thoroughly eviscerated the concept of miracles.20 Yet he believed in an intervening Providence. Is the answer that Paine was, as George Bernard Shaw said of Joan of Arc, a visionary who was “mentally excessive”?21

Reconciling Paine’s references to Providence with his overarching commitment to reason would be easier if one accepted the view of an unsympathetic commentator that Paine employed mere rhetorical flourishes insincerely manufactured to persuade readers by exploiting their religious beliefs.22 That commentator’s theory falls apart when one recognizes that he restricted analysis to Paine’s early American writings, ignoring Paine having repeatedly invoked Providence from 1775 through 1803 and even doing so on an occasion when manipulative motives made no sense—a private letter to Franklin.23 Aldridge, more convincingly, cited Paine’s invocation of an intervening Providence in that letter to Franklin as evidence Paine had “a firm belief in the doctrine of special providence.”24 Paine’s surviving writings confirm that he was sincere in invoking an intervening Providence.

Teasing out explanations for the apparent disparity in Paine’s thinking between an unyielding devotion to reason and a belief in an intervening supernatural force was furthered through Matthew Stewart’s superb book Nature’s God. Although Stewart did not expressly address Paine’s views on Providence, he carefully studied views of the Deist Founders in contrast to earlier religious beliefs in England and the colonies and observed that the very idea of Providence was transformed by the Deists.25

Some contemporaries of Paine, for example, took the Bible literally and believed that Providence caused many events contrary to laws of nature, such as the Biblical stories of the Sun standing still in the sky for a full day or the Red Sea parting. For example, that “the Bible was divinely revealed and that its miracles were valid were accepted by Samuel Adams “without question.”26 By contrast, for “the deists, a miracle by definition constituted an infraction of the regular and predictable operations of physical reality.”27

Deists generally viewed Providence as causing only events that, while improbable, fully complied with the laws of nature.28 Washington attributed his survival from multiple bullets hitting his coat to the intervention of Providence.29 Improbable but feasible under the laws of nature. Paine attributed his survival during the Jacobin reign to an intervening Providence.30 Improbable but well within the laws of nature. The intervention of Providence, viewed in this way, comports closely with Giordano Bruno’s view that Providence does not override “the operation of nature” and can instead “be explained in terms of natural laws.”31

Deists were, by nature, individualist and unconfined by a fixed set of creeds mandated by a hierarchical church structure. As a result, their beliefs regarding God and Providence varied. Franklin straddled the fence between Deism and other belief systems and remained governed, due to his Puritan upbringing, by assumptions that God was infinitely powerful and infinitely good.32 Those assumptions directed his reasoning towards a conclusion that God’s Providence must sometimes act in ways contrary to the laws of nature.33 Otherwise, Franklin reasoned, God would be either impotent or willing to countenance demonstrably evil actions—results inconsistent with God being infinitely powerful and infinitely good.34

Recall that Paine, by contrast, deduced the existence of God from a logical supposition that God was whatever first created things.35 Unconstrained by assumptions that troubled Franklin, Paine was freed to view Providence as a force that acted in ways fully compliant with the laws of nature.36 But is belief in an intervening Providence ultimately just belief rather than a result of reasoned examination of actual occurrences? Paine may have responded that human abilities to ferret out explanations for actions of God and Providence are severely restricted.

In 1782, Paine asserted that “no human wisdom could foresee” the purposes of expectation that rational inquiry in the future would push further than he could, at that time, into probing that “secret.” Eleven years later, Paine concluded that “the power and wisdom” that God “has manifested in the structure of the Creation that I behold is to me incomprehensible,” and “even this manifestation, great as it is, is probably but a small display of that immensity of power and wisdom by which millions of other worlds, to me invisible by their distance, were created and continue to exist.”38

Some observers accused Paine of thinking too well of himself and his abilities. Remarks by Paine that fed those types of accusations should be balanced against the humility and calm wonder he displayed when observing nature and the universe. Conceivably, and consistent with the later musings by Keats, his belief in an intervening Providence constituted an effort to appreciate and marvel at the “incomprehensible” while remaining otherwise unflinchingly dedicated to rational inquiry.

What effect did Paine’s belief in an intervening Providence have on his overall philosophy and his political and social views? Gregory Claeys argued that Paine’s “social theory owed much to his belief in Providence, which underpinned, for example, the optimistic elements of his theory of commerce.”39 Would a Paine who lacked beliefs in an intervening Providence have penned theories substantially different from those he promulgated? Would he have lacked the optimism and confidence to propound and push the radical and uncompromising views that continue to resonate? If Paine, after exhaustive efforts to tease out everything reason had to offer in his lifetime, experienced “the intense pleasure of not knowing” that Keats praised as a font of human creativity and achievement, that may have reignited fires within his mind even as nighttime candles flickered in his darkening writing rooms.

PROVIDENCE AS FEMALE

The first mystery ultimately remains unresolved. Exploring the second mystery will similarly leave open questions but will, hopefully, provide insight into Paine. Drilling down into what Paine said about Providence, we discover a startlingly unique conviction. Every time Paine referenced gender for the Deity, he identified the Deity as male.40 But every time he referenced gender for Providence—in 1777, 1778, 1782, 1792 and 1802—he identified Providence as female.41

Where did that perspective come from? While in England, Paine was exposed to Quakers, Anglicans and Methodists. Each sect generally viewed Providence as a manifestation of a male God.42 Contemporaries such as Rev. Joseph Priestley and Rev. Richard Price had conveyed the view of Providence as a manifestation of a male God in writings published before Paine emigrated to America.43 References to Providence in Political Disquisitions by James Burgh, which Paine cited several times in Common Sense, nowhere hint at Providence having a female gender.44 French influences may be excluded for many reasons, including the Catholicism of France and Paine’s anti-Papist views, but it suffices that Paine publicly identified Providence as female at least three times before first travelling to France in 1780.45

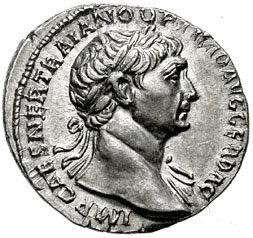

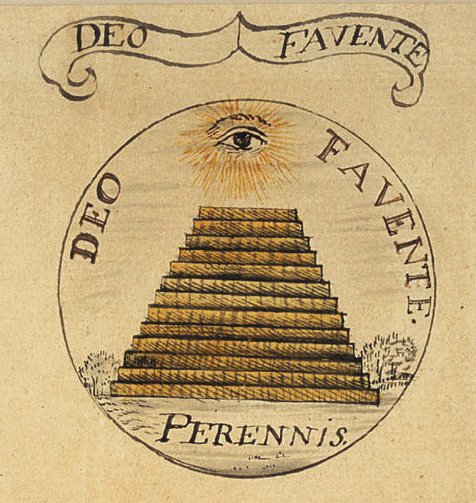

One Paine biographer, after noting Paine’s identification of Providence as female in Rights of Man, observed, with understatement, that “few references to Providence in this period characterized it as female.”46 Few indeed. One must reach back to Imperial Rome to find general beliefs in Providence being female. Unconnected dots invite speculation that Paine may have absorbed a belief in a female Providence from contemporary discussions of that Roman source. In ancient Rome, “Providentia” was viewed as a female “divine personification of the ability to foresee and make provision.”47 Macrobius, a Roman author who wrote about paganism about 400 CE, declared that “providence was personified as a proper goddess in her own right.”48

“In the late Republic PROVIDENTIA was that foresight which…helped to secure the continued and peaceful existence of the state, preserving it against external or internal dangers.”49 Refraining from learning Latin in Thetford Grammar School, Paine said, “did not prevent” him “from being acquainted with the subjects of all the Latin books used in the school.”50 Reference to “Latin books” is sparse in his writings, although that is unsurprising for an author known for minimalistic citations to other authors. What “Latin books” was he exposed to before first identifying Providence as female that may have influenced him? In several writings that preceded his first identification of Providence as female in Crisis No. 3, published on April 19, 1777, Paine displayed considerable familiarity with Roman times and ways.51 Later references suggest far deeper absorption by Paine of ancient Roman authors, and books about ancient Rome, than is generally assumed.52 With that in mind, Paine may have consumed either an unabridged 1747 or 1755 edition of Polymetis by Joseph Spence, or a 1765 abridged version, most likely sometime after returning from his privateering adventures in 1757.53

The unabridged editions of Polymetis contain detailed discussions about the Imperial Roman belief in female Providence and illustrations of “Providentia” as displayed on Roman coins.54 Paine had multiple opportunities prior to first identifying Providence as female in 1777 to be exposed to Spence’s discussions of a female Providence. Benjamin Martin subscribed to the unabridged 1747 edition of Polymetis and Paine later attended his astronomy lectures and became a friend, so Paine could have borrowed a copy from Martin.55 Alternately, though the purchase price was likely far beyond Paine’s budget, he could have perused a copy of an unabridged edition through the lending libraries then taking hold in London.56 Alternately, Paine could have read a far less expensive abridgment published in 1765 that, like the unabridged version, contained detailed discussions about a female Providence, though with far less content and no “Providentia” illustrations.57

Assume, however, that Paine was not exposed to any of those editions before emigrating in 1774. He still had opportunities, before first identifying Providence as female in April 1777, to have consumed an unabridged edition of Polymetis. The 1775 catalogue of the Library Company of Philadelphia listed the 1755 unabridged edition amongst its holdings.58 Polymetis was sufficiently available in America that Jefferson, in a July 1776 letter, accurately expected that “some library in Philadelphia” would have Spence’s Polymetis.59

Paine rarely mentioned books he had read and sometimes claimed not to have read books that scholars conclude he must have consumed.60 That Polymetisis unmentioned in his writings, particularly since he never attempted to explain his beliefs regarding Providence, is unsurprising. Unabridged editions of Polymetis were filled with citations to Macrobius and Cicero and contained images of the transparently female figure of Providentia as displayed on Roman coins.61 Even the abridged version published in 1765 would have conveyed the essence, noting that “among the “MORAL DEITIES” in Rome, “PRUDENCE (or GOOD SENSE) was received very early as a goddess,…the affairs of human life are by her regulated as they ought to be” and “She is called also Providentia but when they used it for divine providence, the usual inscription on medals is, PROVIDENTIA DEORUM,” while a different name is used for human prudence.62

Spence, in Polymetis, conveyed critiques of classically based educational methods that were remarkably like critiques that Paine articulated later.63 Spence took “aim in the Polymetis at the classical scholarship of his day, which he” found “obscure and pedantic, and generally unhelpful in explicating the texts themselves” and “also question[ed] the need for a classical education grounded in a thorough study of Latin and Greek, which he consider[ed] an unnecessary preparation for most professions.”64 Paine was similarly critical of classical scholarship for its own sake as opposed for purposedriven uses.65 Cursory glances through Polymetistelegraph that the intellectual sponge that Paine was in his twenties after returning from privateering adventures would have thrilled at its content. With Paine’s fascination regarding astronomy, Paine may have found Macrobius interesting because he authored a text “that transmitted classical astronomical knowledge to medieval Latin Europe” by commenting on a work of Cicero that Macrobius included in his work.66

The 1755 unabridged edition and the 1765 abridgement were extensively advertised in London papers that Paine likely read.67 As noted earlier, a copy of the 1755 edition of Polymetis was available in Philadelphia, at the Library Company founded by Franklin, after he arrived in Philadelphia in November 1774 and before April 1777.68 The Library Company was open to the public well before Paine emigrated and with Paine’s bibliophilia being a quality about which we have little doubt, it is fair to assume he spent many hours there.69 While other books published in England before Paine emigrated noted the Roman belief that Providence was female, their references were so slight and obscure that they are a far less likely source for Paine’s belief.70 If his belief is derived from a book, Polymetisis the prime candidate.

May we connect these disparate dots to create a coherent constellation, in Roman style, displaying the origin of Paine’s belief in a female Providence? Tempting as that may be, evidentiary gaps preclude, for now, a definitive conclusion. But sifting the soil of Paine’s contemporaries during the Revolutionary Era as an alternative source is sufficiently unpromising to return us, by deductive reasoning, to Polymetis.

Many Deist Founders, when referencing gender at all, identified God as male and Providence as either male or a manifestation of a male God.71 When Paine referenced gender regarding God, he similarly identified God as male and never as female.72 Paine was unique among his American contemporaries in identifying Providence as female.73

John Adams referenced Providence with some frequency, usually with no gender reference. On occasions when Adams referenced gender, he identified Providence as genderless three times and as male twelve times, never suggesting that Providence was female.74 Jefferson referenced Providence more infrequently also without usually referencing gender. Of the occasions when Jefferson referenced gender, he identified Providence as genderless twice, as male six times and, like Adams, never suggested a female gender.75 Washington referenced an intervening Providence with extraordinary frequency, usually without identifying gender beyond implying a male gender by equating God with Providence.76 Of the occasions when Washington expressly referenced gender for Providence, eighteen identified Providence as genderless (“it” or “its”).77 Nine identified Providence as male (“he” or “his”).78 Curiously, Washington twice deviated from his general practices by identifying Providence as female in 1777 and 1783.79

No surviving information sheds light on those two deviations from Washington’s general practices. Paine’s identifications were an unlikely influence.80 Conceivably, Washington was exposed to Polymetis since George Wythe—a sufficiently close friend that Washington “settled into” Whyte’s home for a while— apparently had a copy in his personal library.81 But, with Washington having only used female pronouns for Providence twice among the many occasions that he expressed or implied a gender, could they merely have been slips of the pen? What is certain is that Paine, who was extraordinarily careful with his word choices, consistently and repeatedly Providence as female, even emphasizing “her” on one occasion.82

A possible explanation is that Paine’s unique perspective among the Founders about the differing genders of God and Providence is unattributable to any, so why did he develop that perspective without any outside influence? Did his identification of Providence as female reflect the respect he had for women as equal human beings?83 There is sparse evidence that Paine’s relatively egalitarian views towards women, while remarkably modern for the time, would have sufficiently evolved by April 1777 to have inspired that initial identification of Providence as female.84 More broadly, it seems inconceivable, that Paine would have refrained from his general practice of expressly articulating thought processes that were uniquely his regarding his identification of Providence as female if he had developed that concept entirely on his own.uniquely his regarding his identification of Providence as female if he had developed that concept entirely on his own.

Deductive reasoning and circumstantial evidence suggest that the most likely influence was reports of ancient Roman beliefs as relayed in one or more sources available to him before, and after, he emigrated. For now, Polymetis seems the most likely inspiration for Paine identifying Providence as female.

Did his identification of God as male and Providence as female indicate that, unlike other Deist Founders, Paine perceived Providence as an entity separate from God? That has intriguing implications but, given limited evidence, cannot proceed beyond the question being posed.85 The only Paine biographer who noted Paine’s practice of identifying Providence as female and God as male reported that it troubled him for quite a while.86 Unfortunately, his conclusions were unhelpful, declaring, with evidence-free confidence, that “Paine envisioned Providence as an all-encompassing, nurturing she-goddess of nature” and that “Paine’s Providence was the First Cause, the giver of all life,” and “created the universe,…”87 Paine’s writings directly belie those conclusions, with that very biographer repeatedly noting that Paine instead stated that the Creator was a male God and, indeed, was the “sole” Creator.88

Since Paine also consistently identified Nature as female when referencing gender regarding Nature, did he equate Providence with Nature?89 His separate expressions of gratitude to both “nature and providence” suggest that he did not equate them, particularly with Paine generally minimizing redundancy in his writings.90 More telling, he did not view Nature as actively intervening in human affairs like Providence. Instead, he viewed the laws of Nature as imposing limits on human affairs and on Providence.

As with many aspects of Paine, the only clues are disclosed through his surviving writings, which offer tantalizing hints that will likely remain perennially unresolved. Ultimately, we cannot know why he identified God as male and Providence as female. We are, regarding his reasoning, consigned to the “intense pleasure of not knowing.”

EXPLAINING THE INEXPLICABLE

Ultimately, what humans—unlike other species so far as we know—perennially confront is how to explain the inexplicable. For humans, that results in concepts like God and Providence. How did Paine— the Man of Reason dedicated in his bone marrow to rational thought—explain the inexplicable? Paine struggled to develop the best answers he could given the limitations of what was rationally detectable in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries. Recognizing how little could then be explained through reason and the vastness of what was inexplicable, his enlistment of and reliance on Providence is understandable.

Did he consider his belief in an intervening Providence grounded on reason? He never either said that it was and articulated any rationale in his surviving writings. He may instead have explored the issues as deeply as rational inquiry carried him and then, in proto-Keats fashion, have embraced the unknowable that he labeled “Providence” while refraining from “irritable reaching for fact and reason.” That we, in the 21st Century, may reach different conclusions through reason does not mean that Paine was less dedicated to reason. Then, and today, firm devotees of reason rather than revelation necessarily marvel daily at inexplicable events and at the intricacies presented by Nature that are well beyond the capacities of humans to explain.

ENDNOTES

- Jack P. Greene, “Paine, America, and the ‘Modernization’ of Political Consciousness, 93, Political Science Quarterly 73-92 (Spring, 1978), 76- 81 (Paine frequently advocated for people to insist on being governed by rationalsystems and was himself devoted to rational thinking). The biography title best capturing Paine may be Alfred Owen Aldridge, Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott & Co., 1959).

- E.g., John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1995), 500- 503.

- Thomas Paine, Age of Reason [1793], The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. P. Foner (New York: The Citadel Press, 1945), 1:463-514; Age of Reason: Part Second [1795], Paine Writings, 1:514-604.

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:463- 514; Age of Reason: Part Second [1795], Paine Writings, 1:514-604. Religious views expressed in Age of Reason were “based entirely on the observation of nature and reasoning from it.” Aldridge, Man of Reason, 231. “Paine applied tests of reason to scripture,” and “rejected almost everything,” with the “notable exception [of] creation, because he could actually see the results of it”—using “his own rational teststo question every event in the Bible.” Jack Fruchtman, Jr., Thomas Paine and the Religion of Nature, (Baltimore: MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 159 & 160. Paine identified within the Bible a few exceptions grounded on actual observations of “creation” and, therefore, consistent with rational inquiry. Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:484-486.

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:486. This logic, compelling in the late 18th Century, was drawn in question by Darwin but only genuinely challenged with the advent of modern physics. Full disclosure calls for noting that, applying the limited knowledge gleaned through the present day, your author views beliefs in a Deity and an intervening Providence to be precluded by rational inquiry while fully respecting Paine’s ability to rationally reach different conclusions using knowledge available while he lived. As indicated elsewhere, the boundary between rational inquiry and the inexplicable is individual and shifts with time and societal changes.

- Paine proffered a rationale for his belief in a Deity. Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:486. But on none of the occasions that he expressed belief in Providence as an intervening force did he ever broach reasons for that belief. “Crisis No. 1” [1776], Paine Writings, 1:55; “Crisis No. 3” [1777], Paine Writings, 1:75; id, Paine Writings, 1:87; “Crisis No. 5” [1777], Paine Writings, 1:120; “Crisis No. 6” [1778], Paine Writings, 1:131; “Crisis No. 8” [1780] Paine Writings, 1:160: “Crisis No. 9 [1780], Paine Writings, 1:166: “The Crisis Extraordinary” [1780], Paine Writings, 1:185-186, “Crisis No. 10” [1782], Paine Writings, 1:193; id, Paine Writings, 1:193-194; “Crisis No. 13” [1783], Paine Writings, 1:235; Rights of Man, Part the Second [1792], Paine Writings, 1:366; “An Act for Incorporating the American Philosophical Society, held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge” [1780], Paine Writings, 2:39; Letter No. 3 on Peace and Newfoundland Fisheries, [1778], Paine Writings, 2:202; Public Good [1780], Paine Writings, 2:305; “To the Sheriff of the County of Sussex [1792] Paine Writings, 2:464; “Addressto the People of France” [1792], Paine Writings, 2:539; id, Paine Writings, 2:540; “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” November 15, 1802, Paine Writings, 2:909; “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” December 29, 1802, Paine Writings, 2:920; “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” February 2, 1803, Paine Writings, 2:931; March 4, 1775 letter to Franklin, Paine Writings, 2:1130; “To the Chairman of the Society for Promoting Constitutional Knowledge [1792], Paine Writings, 2:1325-1326. Ironically, hissole mention of Providence in Age of Reason wasto dismiss “Christian mythology” that believed in a pantheon of Gods and Goddesses. Age of Reason [1794], Paine Writings, 1:498). De-attributed works are excluded from consideration. Thomas Paine National Historical Association, “Works Removed from the Paine Canon,” https://thomaspaine.org/writings. html#works-removed-from-the-paine-canon last accessed 6/20/2024.

- “Crisis No. 3” [1777], Paine Writings, 1:75 (“… embarrass Providence in her good designs”); id, Paine Writings, 1:87 (“…Providence, who best knows how to time her misfortunes as well as her immediate favors, chose this to be the time, and who dare dispute it?”); “Crisis No. 6” [1778], Paine Writings, 1:131 (“To the interposition of Providence, and her blessings on our endeavours, …are we indebted …”); “Crisis No. 10” [1782], Paine Writings, 1:193 (“…providence, for seven yearstogether, has put [the King] out of her protection,…” (italicsin original)); id, Paine Writings, 1:193-194 (“Untainted with ambition, and a stranger to revenge, [America’s] progress hath been marked by providence, and she, in every stage of the conflict, has blest [America] with success”); Rights of Man, Part the Second [1792], Paine Writings, 1:366 (“Such a mode of reasoning … finally amounts to an accusation upon Providence, asifshe had left to man no other choice with respect to government than between two evils,…”); “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” December 29, 1802, Paine Writings, 2:920 (“They have not yet accused Providence of Infidelity. Yet according to their outrageous piety,she must be as bad as Thomas Paine;she has protected him in all his dangers,…” (italicsin original)).

- Conway, observing that “among these papers burned in St. Louis were the two volumes of Paine’s autobiography and correspondence seen by Redman Yorke in 1802,” characterized the loss as a true “catastrophe.” Moncure Daniel Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: G. P. Putnam’s & Sons, 1908), 1:xx-xxi.

- For examples of those remarks,see “Crisis No. 10” [1782], Paine Writings, 1:193 and Age of Reason, Paine Writings, 1:486.

- During a walk in 1817, “several things dovetailed” for Keats into his developing the concept of “Negative Capability,” the ability to comfortably be “in uncertainty.” December 22, 1817, letter from John Keatsto George & Thomas Keats, The Poetical Works and Other Writings of John Keats(London: Reeves & Turner, 1883), 3:99, italicsin original. Keats perceived that, for writers “of Achievement” to embrace rather than battle the unexplainable is a criticalspark to human creativity and inventiveness. One biographer observed that it was “precisely the ability to hold contrary truthsin creative tension which Keatssaw asthe essential quality” possessed by writers “of Achievement.” John Barnard, John Keats (Cambridge, England: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1987), 51. Paine’s ability to hold contrary truths in creative tension may be at the heart of the two mysteries we explore here.

- December 22, 1817, letter from Keats, Poetical Works, 48.

- December 22, 1817, letter from Keats, Poetical Works, 48.

- Robert Giddings, John Keats (Boston, MA: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1968), 173; John Keats, “Notes on Milton’s Paradise Lost,” Poetical Works, 3:24 (“What creates the intense pleasure of not knowing? A sense of independence, of power, from the fancy’s creating a world of its own by the sense of probabilities.”)

- John F. Berens, Providence and Patriotism in Early America, 1640-1815 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1978), 81-111.

- E.g., Samuel Adams, “Resolution of the Continental Congress,” The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1907), 3:414-416; February 28, 1797 letter from John Jay to Rev. Jedediah Morse, The Correspondence and Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry P. Johnson (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), 4:225 (“except the Bible there is not a true history in the world”); John Witherspoon, “A Practical Treatise on Regeneration,” The Works of The Rev. John Witherspoon (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1802), 1:93-265, John Witherspoon, “The Dominion of Providence Over the Passions of Men,” The Works of The Rev. John Witherspoon (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1802), 3:17-46; Jeffry H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 20-21, 90-91. “Sam Adams and John Jay…were orthodox, even conservative Christians, while Franklin, Jefferson, and Paine were deists.” Berens, Providence and Patriotism in Early America, 1640-1815, 107.

- See “ADAMS, John,” Joseph McCabe, A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists (London: Watts and Co., 1920), 7-8 (1920); “ALLEN, Colonel Ethan, Biographical Dictionary, 16; “FRANKLIN, Benjamin,” Biographical Dictionary, 267; “JEFFERSON, Thomas,” Biographical Dictionary, 387- 388; “LAFAYETTE, the Marquis M. J. P. R. Y. G. M. de,” Biographical Dictionary, 412-413; “MADISON, James,” Biographical Dictionary, 471-472; “MORRIS, Gouverneur,” Biographical Dictionary, 929-930; “PAINE, Thomas,” Biographical Dictionary, 577-578; WASHINGTON, George,” Biographical Dictionary, 870-872. A “firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence” wasinvoked in the Declaration of Independence. “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/foundingdocs/declaration-transcript. The dominant belief among Foundersin an intervening Providence is expressed in the “Eye of Providence” displayed on all one-dollar bills and on the Great Seal of America. Leonard Wilson, The Coat of Arms, Crest and Great Seal of the United States of America: The Emblem of the Independent Sovereignty of the Nation (San Diego, CA: Leonard Wilson, 1928), pp. 28-29; U. S. Department of State, The Great Seal of the United States(Washington D.C.: Office of Media Services, Bureau of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of State, 1976). Superficially, beliefs of Deist Foundersin an intervening Providence seem to differ from those of prior Deists. Giordano Bruno, executed in 1600, created a central tenet of Deism when he “rejected the idea that Providence intervenes in the operation of nature” and that what “are called miracles can be explained in terms of natural laws.” Edward L. Ericson, The Free Mind Through the Ages(New York: F. Unger Publications, 1985), 56. As noted later, the beliefs of the Deist Founders, interrogated more deeply,suggests a heritage deriving from Bruno.

- One commentator opined that “[n]obody believed more deeply than radical deists in an allwise Providence.” Henry F. May, Ideas, Faiths, and Feelings: Essays on American Intellectual and Religious History, 1952-1982 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 141. May’s opinion is debatable, particularly when compared to contemporarieslike Rev. John Witherspoon, but, even if true, would beg the question of why “radical deists” held such beliefs.

- “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” December 29, 1802, Paine Writings, 2:920. In 1804, Paine contributed numerous articlesto Elihu Palmer’s Prospect magazine. “Prospect Papers” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:789-830. The religious arguments of Paine and Palmer—who was a substantially deeper thinker regarding religious issues—mostly coordinated but may have clashed regarding the existence of an intervening Providence. Kirsten Fischer, American Freethinkers: Elihu Palmer and the Struggle for Religious Freedom in the New Nation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 174-221; Kerry S. Walters, American Deists: Voices of Reason and Dissent in the Early Republic (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1992), 244-277 (discussing Palmer); G. Adolf Koch, Republican Religion: The American Revolution and the Cult of Reason (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1933), 51- 73 (same); Herbert M. Morais, Deism in Eighteenth Century America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1934), 128-138. Intriguingly, Paine’slast known reference to an intervening Providence was in February 1803 (see n7 supra) before he first published in Palmer’s Prospect. Whether that is coincidence or influenced by Palmer must remain in the realm of speculation.

- Thomas Paine, “Thoughts on Defensive War” [1775], The Pennsylvania Magazine or the American Monthly Museum for July 1775 (Philadelphia, July 1775), 313-314; The Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. M. Conway (New York: G. P. Putnam’s, 1894), 1:55 (attribution to Paine).

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:505- 511; Age of Reason, Part the Second [1796], Paine Writings, 1:520 & 1:587.

- Bernard Shaw, Preface, Saint Joan, A Chronicle Play in Six Scenes and an Epilogue (London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2001), 13-14.

- Nicholas Guyatt, Providence and the Invention of the United States, 1607-1876 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 7-8 (assuming, based on Paine’s assault on Christianity in Age of Reason, that, in Common Sense and the Crisis series, Paine’s “public piety diverged from” his “private convictions” and that he cynically “adopted providential language precisely because” he realized “that many Americans accepted its premises”).

- Guyatt, Providence and the Invention of the United States, 7-8, 89-90, 95, 105, 148, 152, 155- 157, 169, 171 (noting only Paine’sreferencesto an intervening Providence in Common Sense and the Crisis series and not Paine’s later references). See n6 supra (noting eleven references by Paine to an intervening Providence in writings other than Common Sense and the Crisis series including a reference as late as 1803).

- Aldridge, Man of Reason, 53. See also Aldridge, Man of Reason, 276 (citing 1802 invocation).

- Matthew Stewart, Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Revolution (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014), 190-192.

- Morais, Deism in Eighteenth Century America, 97.

- Walters, American Deists, 29.

- Stewart, Nature’s God, 190-192. John Fea, by contrast, opined that being a Deist and believing in an intervening Providence are entirely incompatible. John Fea, “Deism and Providence,” Current, August 19, 2011, https://currentpub.com/ 2011/08/19/deism-and-providence/

- June 12, 1754, letter to Robert Dinwiddie, Washington Writings, 1:76; July 18, 1755, letter to John Augustine Washington, Washington Writings 1:152. See Stewart, Nature’s God, 190-192.

- “Letter to the Citizens of the United States,” December 29, 1802, Writings of Paine, 2:920.

- Ericson, The Free Mind Through the Ages, 56.

- Benjamin Franklin, “A Lecture on the Providence of God in the Governance of the World,” The Complete Works of Benjamin Franklin, ed. John Bigelow (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1888), 7:489-497.

- Benjamin Franklin, “A Lecture on the Providence of God,” 7:489-497.

- Benjamin Franklin, “A Lecture on the Providence of God,” 7:489-497.

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:486.

- Examining those occasions when Paine cited an intervening Providence, each implicates a situation that comports with the laws of nature, even if improbable. See citations at n6 supra.

- “Crisis No. 10” [1782], Paine Writings, 1:193.

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:486. See Stewart, Nature’s God, 190.

- Gregory Claeys, Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought (Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989), 204-206 (Paine “extended his notion of Providence unreasonably far”)

- References to God as “He” “he” “His” “his” “Him” “him” “Himself” “himself” “Father” “father’s”: “Crisis No. I” [1776], Paine Writings, 1:50- 51; Rights of Man-Part the First [1791], Paine Writings, 1:452; Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:478; id, Paine Writings, 1:483; id, Paine Writings, 1:486; id, Paine Writings, 1:487; id, Paine Writings, 1:493; id, Paine Writings, 1:497; id, Paine Writings, 1:506; id, Paine Writings, 1:510; id, Paine Writings, 1:512; Age of Reason-Part the Second [1795], Paine Writings, 1:523; id, Paine Writings, 1:529; id, Paine Writings, 1:583; id, Paine Writings, 1:584; id, Paine Writings, 1:595; id, Paine Writings, 1:601; id, Paine Writings, 1:602; Agrarian Justice [1797], Paine Writings, 1:609; Epistle to Quakers[1776], Paine Writings, 2:58; “The Forester II,” [1776], id., Paine Writings, 2:79; “A Serious Addressto the People of Pennsylvania on the Present Situation of their Affairs” [1778], Paine Writings, 2:295; “Answer to Four Questions on the Legislative and Executive Powers” [1791], Paine Writings, 2:525; “A Letter to the Hon, Thomas Erskine” [1797], Paine Writings, 2:729; id, Paine Writings, 2:733; id, Paine Writings, 2:738; id, Paine Writings, 2:744; “The Existence of God” [1797], Paine Writings, 2:749; id, Paine Writings, 2:750; Paine Writings, 2:754; “Extractsfrom a Reply to the Bishop of Llandaff” [1796-1802], Paine Writings, 2:776; id, Paine Writings, 2:785; id, Paine Writings, 2:786-787; “Remarks on R. Hall’s Sermon” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:790; “Of the Word ‘Religion,’ and Other Words of Uncertain Signification” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:792; id, Paine Writings, 2:793; “Of the Religion of Deism Compared with the Christian Religion, and the Superiority of the Former over the Latter” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:797; id, Paine Writings, 2:798; id, Paine Writings, 2:800; id, Paine Writings, 2:802; “Of the Sabbath Day in Connecticut” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:804; id, Paine Writings, 2:805; “Of the Old and the New Testament” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:806; “To John Mason” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:813; id, Paine Writings, 2:814; id, Paine Writings, 2:815; “On Deism, and the Writings of Thomas Paine” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:816; id, Paine Writings, 2:817; “Biblical Blasphemy” [1804], Paine Writings, 2:824; “Examination of the Prophecies” [1807], Paine Writings, 2:876; id, Paine Writings, 2:886; id, Paine Writings, 2:887; id, Paine Writings,, 2:888; id, Paine Writings, 2:889; id, Paine Writings, 2:890; id, Paine Writings, 2:891; “My Private Thoughts on a Future State,” Paine Writings, 2:892; id, Paine Writings, 2:893;“Predestination: Remarks on RomansIX, 18- 21” [1809], Paine Writings, 2:896.

- See citations in n7 supra.

- Daniel Gittens, Remarks on the Tenets and Principles of the Quakers as Contained in the Theses Theologica of Robert Barclay (London: J. Betterman, 1758), xii, xviii, 100, 149, 150, 157, 206 & 312 (Quaker views) William Craig Brownlee, A Careful and Free Inquiry into the True Nature and Tendency of the Religious Principles of the Society of Friends, Commonly Called Quakers (Philadelphia: John Mortimer, 1924), 107, 108, 110, 135, 149, 158, 161, 177, 184, 212, 268, (Quaker viewsin 18th century); Quaker anecdotes, ed. Richard Pike (London: Hamilton, Adams, & Co., 2nd ed. 1881), 24, 206-207, 230, 266-267, 272 & 300 (same); Alfred Plummer, The Church of England in the Eighteenth Century (London: Methuen, 1910), 97, 157, 218 (Anglican views in 18th century); A New History of Methodism, eds. Townsend, Workman, & Eayrs (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1909), 1:28- 29, 1:35, 1:66, 1:229, 1:448, 2:36, 2:45, 2:230, 2:287, 2:289 (Methodist views in 18th century).

- Priestley and Price routinely, in writings published before Paine emigrated, referenced the “Providence of God” or “Divine Providence” and never hinted at a female gender for Providence. E.g., Richard Price, “Dissertation I on Providence,” Four Dissertations (London: A. Millar & T. Cadell, 1767), 3- 194; Joseph Priestley, No Man Liveth to Himself: A Sermon Preached Before and Assembly of Dissenting Ministers (Warrington, 1764), viii, 19 & 33.

- A. Owen Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American Ideology (Newark, NJ: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 52-53 & 80 (Paine’s citation to Burgh’s book in Common Sense); J. Burgh, Political Disquisitions: An Enquiry into Public Errors, Defects, and Abuses. Illustrated By, And Established Upon Facts and Remarks, Extracted from a Variety of Authors, Ancient and Modern, (London: Edward & Charles Dilly, 1774) 1:486, 3:85, 3:91, 3:121, 3:162, 3:183, 3:205, 3:257 (references to Providence).

- “Crisis No. 3” [1777], Paine Writings, 1:75; “Crisis No. 3” [1777], Paine Writings, 1:87; “Crisis No. 6” [1778], Paine Writings, 1:131. Paine’s belief in a female Providence certainly did not derive, for example, from any Catholic belief in an intervening Virgin Mary. Even Protestants in France firmly rejected Mary cults(e.g., David Garrioch, “Religious Identities and the Meaning of Things in EighteenthCentury Paris,” 3, French History and Civilization 17- 25, (2009), 22) and Paine was unquestionably anti-Papist (e.g., Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American Ideology, 63).

- Fruchtman, Thomas Paine and the Religion of Nature, 188, n27.

- “Providentia,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org wiki/Providentia#cite_note1, citing J. Rufus Fears, “The Cult of Virtues and Roman Imperial Ideology,” Aufstieg und Niedergang (1981), 886. See “Providentia,” Encyclopedia Mythica,https://pantheon.org/articles/p/ providentia.html#google_vignette.

- Theodorus P. van Baaren, “ProvidenceTheology,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com /topic/Providence-theology.

- Martin Percival Charlesworth, “Providentia and Aeternitas,” 29, The Harvard Theological Review 107-132 (April 1936), 109.

- Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:496.

- See n7 supra. “Thoughts on Defensive War” [July 1775], Paine Writings, 2:54 (the “Romans held the world in slavery, and were themselvesthe slaves of their emperors”); Forester’s Letter No. 1 [April 3, 1776], Paine Writings, 2:61 (addressing a contemporary opponent using the pseudonym Cato by stating that the “fate of the Roman Cato is before his eyes”); “A Dialogue Between the Ghost of General Montgomery Just Arrived from the Elysian Fields; and an American Delegate, in a Wood Near Philadelphia” [May 1776], Paine Writings, 2:92 (listing “Grecian and Roman heroes” by name); “Retreat Acrossthe Delaware” [January 29, 1777], Paine Writings, 2: 95 (“the names of Fabius”— a Roman hero —“and Washington will run parallel through eternity”). Aldridge identified many occasionsthat Paine referenced classical authors or figuresfavorably or unfavorably. A. Owen Aldridge, “Thomas Paine and the Classics,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 370-380 (Summer, 1968), 370-373.

- “Crisis No. 5 [1778], Paine Writings, 123-124 (extended discussion of Rome and Greece); Age of Reason [1793], Paine Writings, 1:491-492 (same). In 1795, Paine expressly listed the “works of genius” by Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Cicero, and others “as works of genius,” also mentioning Herotodus, Tacitus and Josephus. Age of Reason: Part the Second [1795], Paine Writings, 1:520. Later in life, Paine expressed admiration for Cicero at considerable length because he advocated rational thought. “Examination of the Prophecies of the New Testament…” [1807], Paine Writings, 2:882-886; Meyer Reinhold, Classica Americana: The Greek and Roman Heritage in the United States(Detroit, MI: Wayne University Press, 1984), 105-106; Aldridge, “Thomas Paine and the Classics,” 371-372.

- Keane, Paine, 41-44.

- Joseph Spence, Polymetis, or, An Enquiry Concerning the Agreement between the Works of the Roman Poets, and the Remains of the Antient Artists(London: R. & J. Dodsley, 2nd Edition with Corrections by the Author, 1755), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t25b8jp2 x, 138, 150-151 (Roman belief in female Providence; Joseph Spence, Polymetis, or, An Enquiry Concerning the Agreement between the Works of the Roman Poets, and the Remains of the Antient Artists, (London: R. & J. Dodsley, 1st Edition, 1747), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.3901505709 9940, 138, 150-51, 161 (same). Those discussionsin Polymetis were partly supported by a citation to Cicero for the proposition “Providentia deorum mundus administrator.” (Italics added.) The 1747 and 1755 unabridged editions were available in the late 1750s when Paine, living off privateering profits, frequented London bookshops, likely borrowed library booksfor a small fee, and attended astronomy lectures by Benjamin Martin. Keane, Paine, 41-44; Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations(New York: Viking, 2006), 22, (Martin as friend).

- Joseph Spence, Polymetis, 1st Ed., https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp. 39015057099940, x.

- In 1760, an unabridged edition was advertised for “2l. 12s. 6d.” The Public Advertiser” (London, August 6, 1760), 4). Keane, Paine, 41-44. See Eleanor Lochrie, A Study of Lending Libraries in EighteenthCentury Britain, University Of Strathclyde (Thesis, September 2015), https://local.cis.strath.ac. uk/wp/extras/msctheses/papers/strath_cis_publicati on_2684.pdf.

- Joseph Spence, A Guide to Classical Learning, or, Polymetis Abridged (London: R. Horsfeld, 1765), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.fl1e34. 153-154, text & note c (same). The abridgementsold for three shillings. The Public Advertiser (London, February 22, 1766), 4), far less than the unabridged version (e.g., The Public Advertiser (London, August 6, 1760), 4).

- Library Company of Philadelphia, The Second Part of the Catalogue of Books, of the Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Robert Aitken, 1775), 55 (listing the 1755 edition of Spence’s Polymetis as No. 292 in its holdings). The Library Company wasfounded several decades earlier by Paine’sfriend, Benjamin Franklin. Austin K. Gray, Benjamin Franklin’s Library: A Short Account of the Library Company of Philadelphia 1731-1931 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937), 7-17. “Members could borrow booksfreely and without charge” and nonmembers could read books within the library and even borrow books. “At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin”: A Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: York Graphic Services, 1995), 14.

- July 20, 1776, letter from Jefferson to John Page, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/ 01-01-02-0189

- E.g., Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American ideology, 95-122.

- References to Cicero: Spence, Polymetis, 2nd ed., title page quote, iii, 8-13, 15, 16, 21, 23, 29, 31, 38, 40-41, 46-47, 49-50, 57-58, 68-69, 92, 95, 103- 104, 114, 134-135, 137-140, 143-144, 150, 164, 166, 168, 172, 174, 179-180, 182, 188, 190, 193, 195-196, 207-209, 214, 220, 225, 258, 266-267, 272, 279, 287 & 316. Referencesto Macrobius: Spence, Polymetis, 2nd ed., v, 17, 20, 26, 51, 58-59. 64, 116, 174, 193, 196-198, 288 & 315. Images of Providentia: Spence, Polymetis, 1st ed., # 229, https://hdl.handle.net /2027/mdp.39015057099940?urlappend=%3Bseq=2 29%3Bownerid=113489623-228; Spence, Polymetis, 2nd ed., #225, https://hdl.handle.net /2027/gri.ark:/13960/t25b8jp2x?urlappend=%3Bseq =225.

- Spence, A Guide to Classical Learning, 153-154, text & note c.

- Maiora, “Classical Almanac: Joseph Spence,” EcBlogue: A Classics Blog, https://classicsblogging. wordpress.com/2009/04/28/classical-almanacjoseph-spence/ Compare Aldridge, “Thomas Paine and the Classics,”, 370-380.

- Maiora, “Classical Almanac: Joseph Spence,” EcBlogue: A Classics Blog.

- Aldridge, “Thomas Paine and the Classics,”370- 380.

- Latura, “Milky Way Vicissitudes: Macrobius to Galileo,” 18 Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 319-325 (2018), DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1477993, 320, 322 & 324.

- A combined total of 67 advertisements appeared for those two versions in The Public Advertiser in London from August 3, 1758 to December 29, 1772. Search for Polymetisin London County newspapers from 1700 to 1774, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com /search/?query=polymetis&p_province=gb eng&p_county=greater%20london&dr_year=1700- 1774&sort=paper-date-asc

- In 1775, the holdings of the Library Company included a copy of the 1755 edition of Polymetis. See n7 supra. Paine arrived in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774. Frank Smith, “The Date of Thomas Paine’s First Arrival in America,” 3, American Literature 317- 318. (November 1931). Paine’s first known identification of Providence asfemale wasin April 1777. “Crisis No. 3” [April 19, 1777], Paine Writings, 1:75 & 1:87.

- See n55 supra.

- E.g., Edward Herbert, The Antient Religion of the Gentiles, and Causes of their Errors Consider’d (London: John Nutt, 1705), 95-96 (Romans, “by her, mean Divine Providence…”).

- Franklin regularly referenced Providence as a manifestation of God, rarely referenced gender regarding Providence, and never identified Providence as a manifestation of God, rarely referenced gender regarding Providence, and never identified Providence asfemale. Benjamin Franklin, The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, ed. A. Smyth (New York: The Macmillan Co. 1905 to 1907), 1:221- 439, 2:1-470, 3:1-483, 4:1-471, 5:1-555, 6:1-477, 7:1-440, 8:1-651, 9:1-703 & 10:1-510. See Walters, American Deists, 53-55 & 74-75 (Franklin); Walters, American Deists, 122-124 (Jefferson); Walters, American Deists, 143, 146 & 148-155 (Ethan Allen). See nn58-62 infra.

- See n30 supra.

- See n7 supra.

- When Adams referenced gender regarding Providence, he sometimes identified Providence as being genderless(“it” “its”): John Adams, Diary Entry of March 9, 1774, Diary, The Works of John Adams, ed. C. Adams(Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown, 1851), 3:110; Discourses on Davila; A Series of Papers on Political History by an American Citizen, Adams Works, 6:396; “To the Young Men of the City of New York,” Adams Works, 9:198; May 22, 1821, letter to David Sewall, Adams Works, 10:399. More often, when he referenced gender, Adamsidentified Providence as male (His” “his”): Diary Entry of March 2, 1756, Diary, Adams Works, 2:8; Diary Entry of June 14, 1756, Adams Works, 2:22; Diary Entry of October 24, 1756, Adams Works, 2:221; Diary Entry of June 9, 1771, Adams Works, 2:274; Works on Government, Adams Works, 4:220; id, Adams Works, 4:413; “Inaugural Speech to Both Houses of Congress, 4 March 1797,” Adams Works, 9:111; Adams, “Speech to Both Houses of Congress, 8 December 1798,” Adams Works, 9:128; Adams, “Speech to Both Houses of Congress 3 December 1799,” Adams Works, 9:128; December 26, 1806 letter to J.B. Varnum, Adams Works, 9:607; October 4, 1813, letter from Adamsto Jefferson, Adams Works, 10:75; April 5, 1815 letter to Richard Rush, Adams Works, 10:159. No surviving documents reflect Adams identifying Providence as female.

- Jefferson sometimes identified Providence as genderless(“it” “its”): March 4, 1801 Inaugural Address, The Writings of ThomasJefferson, ed. A. Bergh (Washington D.C.: The ThomasJefferson Memorial Association, 1903), 3:320; May 31, 1802 letter to Thomas Law, Jefferson Writings, 19:130. Other times, he identified Providence as male (“his” “His” “he” “Him”): March 4, 1804 Inaugural Address, Jefferson Writings, 3:383; December 5, 1805 Fifth Annual Message to Congress, Jefferson Writings, 3:384; October 12, 1786, letter to Mrs. Cosway, Jefferson Writings, 5:444; February 14, 1807, letter to the Two Branches of the Legislature of Massachusetts, Jefferson Writings, 16:287; March 28, 1809, letter to Stephen Cross, Jefferson Writings, 16:352. Jefferson ambiguously referenced Providence by “their” without indicating any particular gender. Jefferson, Notes on Virginia, Jefferson Writings, 2:242. No surviving documents reflect Jefferson identifying Providence as female.

- Washington’s first recorded reference to an intervening Providence was in 1754. June 12, 1754, letter to Robert Dinwiddie, The Writings of George Washington, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1931), 1:76. The next year, he credited “the miraculous care of Providence” for protecting him from harm “beyond all human expectation.” July 18, 1755, letter to John Augustine Washington, Washington Writings, 1:152.

- April 25, 1773, letter to Burwell Bassett, Washington Writings, 3:133; May 31, 1776, letter to John Augustine Washington, Washington Writings, 5:93; March 1, 1778, letter to Bryan Fairfax, Washington Writings, 11:3; May 30, 1778, letter to Landon Carter, Washington Writings, 11:492; October 18, 1780, letter to Joseph Reed, Washington Writings, 20:213; March 9, 1781, letter to William Gordon, Washington Writings, 21:332; June 5, 1782, letter to Chevalier de la Luzerne, Washington Writings, 24:314; June 30, 1782, lettersto the Ministers, Elders, and Deacons of the Reformed Dutch Church of Schenectady, Washington Writings, 24:391; August 1, 1786, letter to Chevalier de la Luzerne, Washington Writings, 28:501; September 25, 1794, Proclamation, Washington Writings, 33:508; March 30, 1796, letter to Elizabeth Parke Custis Washington, Washington Writings, 35:1; March 30, 1796, letter to Tobias Lear, Washington Writings, 35:5; June 8, 1796, letter to Henry Knox, Washington Writings, 35:85; October 12, 1796, letter to the Inhabitants of Shepard Town and its Vicinity, Washington Writings, 35:242; March 2, 1797, letter to Henry Knox, Washington Writings, 35:409; March 3, 1797, letter to Jonathan Trumbull, Washington Writings, 35:412; August 15, 1798, letter to Reverend Jonathan Boucher, Washington Writings, 36:413-414; November 22, 1799, letter to Benjamin Goodhue, Washington Writings, 37:436.

- July 20, 1776, letter to Colonel Adam Stephen, Washington Writings, 5:313; April 23, 1777, letter to Brigadier General Samuel Holden Parsons, Washington Writings, 7:456; November 30, 1777, General Order, Washington Writings, 10:123; April 12, 1778, General Order, Washington Writings, 11:252; August 20, 1778, letter to Thomas Nelson, Washington Writings, 12:343; April 28, 1788, letter to L’Enfant, Washington Writings, 29:481; October 3, 1789, Thanksgiving Proclamation, Washington Writings, 30:427; July 28, 1791, letter to Lafayette, Washington Writings, 31:324; Jun 10, 1792, letter to Marquis de La Fayette, Washington Writings, 32:54.

- November 8, 1777, letter to Thomas Nelson, Washington Writings, 10:28 (“We must endeavour to deserve better of Providence, and, I am persuaded,she will smile upon us”); October 12, 1783, letter to Chevalier de Chastellux, Washington Writings, 27:190 (“…with the goodness of that Providence which has dealt her favour to us with so profuse a hand”).

- Paine was an unlikely influence on Washington, who first identified Providence as female over six months after Paine had done so. November 8, 1777, letter to Thomas Nelson, Washington Writings, 10:28; “Crisis No. 3” [April 19, 1777], Paine Writings, 1:75 & 1:87. Though Paine and Washington interacted personally shortly before the November 8, 1777, letter, including an extended conversation over breakfast after the Battle of Germantown in early October, no record suggeststhat topic was mentioned. May 16, 1778, letter to Franklin, Paine Writings, 2:1145- 1147; Keane, Paine, 160. Washington’s second identification was a year and half after Paine identified Providence as female in human right to suffrage” and that “women have rights because they are human, not because they are weaker, poorer, or more vulnerable than men”). mythology” (Age of Reason [1794], Paine Writings, 1:498). Hisidentification of Providence asfemale and God as male does not mean that he viewed Providence as a Goddess much less a separate one. “Crisis No. 10.” October 12, 1783, letter to Chevalier de Chastellux, Washington Writings, 27:190; “Crisis No. 10” [March 5, 1782], Paine Writings, 1:193-194. Personal contact in the weeks before October 12, 1783 was precluded by Paine, due to scarlet fever, delaying his visit to Washington’s Rocky Hill estate. Hawke, Paine, 140-142; October 13, 1783, letter to Washington, Paine Writings, 2:1243.

- Washington “settled into” Whyte’s home in September 1781. Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: The Penguin Press, 2010), 410-411. Wythe reportedly had a copy of Polymetis. “Polymetis,” Wythepedia, William and Mary Law Library, https://lawlibrary.wm.edu/ wythepedia/index.php/Polymetis.

- See n7 supra.

- E.g., Botting, “Thomas Paine amidst the Early Feminists,” The Selected Writings of Thomas Paine, eds. I. Shapiro & J. Calvert (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 633 & 643-644 (observing that Paine, in his 1797 Agrarian Justice, made “a creative argument for women’s

- While there are many signals of Paine’s egalitarian attitudes towards women in the 1790s, there are far fewer before April 1777. Paine is no longer deemed the author of “An Occasional Letter on the Female Sex” that appeared in Pennsylvania Magazine in 1775. https://thomaspaine.org/works/works-removedfrom-the-paine-canon/an-occasional-letter-on-thefemale-sex.html

- Some conclude that Paine was a Pantheist rather than Deist or had pantheistic tendencies. Fruchtman, Thomas Paine and the Religion of Nature, 3-4, 52-53; Zaidi, “Rediscovering Thomas Paine and the Sacred Text of Nature,” Left Curve, No. 35 (2011), 138-141, https://www.academia.edu/2327425/Rediscovering_Thomas_Paine_and_the_S acred_Text_of_Nature. Taking Paine at his own word, however, he believed “in one God, and no more” (Age of Reason, Paine Writings, 1:464) and criticized what he viewed as the pantheism of “Christian mythology,” Age of Reason (1794], Paine Writings, 1:498). His identification of Providence as female and God as male does not mean that he viewed Providence as a Goddess much less a separate one.

- Jack Fruchtman, Jr., The Political Philosophy of Thomas Paine (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 178, n15, (after thinking long on Paine identifying Providence as female and God as male, concluding that “at the least he viewed Providence as an immanent divine element, as part of all of nature (or Nature, in deist terms), whereas his vision of God was as creator of the universe, or First Cause”).“Crisis No. 10.” October 12, 1783, letter to Chevalier de Chastellux, Washington Writings, 27:190; “Crisis No. 10” [March 5, 1782], Paine Writings, 1:193-194. Personal contact in the weeks before October 12, 1783 was precluded by Paine, due to scarlet fever, delaying his visit to Washington’s Rocky Hill estate. Hawke, Paine, 140- 142; October 13, 1783, letter to Washington, Paine Writings, 2:1243.

- Fruchtman, Political Philosophy of Paine, 37-38. 88 Fruchtman, Political Philosophy of Paine, 2, 24, 26, 28, 54, 56,

- (“Paine’s deeply held faith in God as the sole creator…” (italics added), 135 and 178, n15.

- Of the many times Paine referenced gender regarding Nature, he identified Nature as genderless once. “The Existence of God: A Discourse at the Society of Theophilanthropists, Paris” [1796], Paine Writings, 2:252. Otherwise, he identified Nature asfemale—not as male or genderless. Common Sense [1776], Paine Writings, 1:13 (“she”); id, Writings of Paine, 1:23; id, Paine Writings, 1:30; id, Paine Writings, 1:34; id, Paine Writings, 1:40); “Crisis No. 6” [1778], Paine Writings, 1:131; “Crisis No. 8” [1780], Paine Writings, 1:160; Rights of Man, Part the First [1791], Paine Writings, 1:260; Paine Writings, 1:321; Rights of Man, Part the Second [1792], Paine Writings, 1:357; Paine Writings, 1:365; id, Paine Writings, 1:367; Paine Writings, 1:371; id. at p. 400; Age of Reason [1795], Paine Writings, 1:509; id, Paine Writings, 1:529; Forester Letter III [1776], Paine Writings, 1:79; Second Letter on Peace and the Newfoundland Fisheries[July 14, 1779], Paine Writings, 1:198; Third Letter on Peace and the Newfoundland Fisheries[July 21, 1779], Paine Writings, 1:201; Dissertations on Government [1786], Paine Writings, 1:411; “Answer to Four Questions,” Paine Writings, 1:525; Paine Writings, 1:527; Prospects on the Rubicon [1787], Paine Writings, 1:631; Decline and Fall of the English System of Finance [1796], Paine Writings, 1:666; Specification of Thomas Paine, A.D. 1788, No. 1667, Constructing Arches, Vaulted Roofs, and Ceiling [1788], Paine Writings, 1:1032; Spring of 1789 letter from Paine to Sir George Staunton, Bart., Paine Writings, 1:1045; June 25, 1801 Letter from Paine to Jefferson [1801], Paine Writings, 1:1048.

- “Crisis No. 13” [1783], Paine Writings, 1:235.