Liberty and Democracy in Dissertation on First Principles of Government (1795)

By Daniel Gomes de Carvalho

ABSTRACT: The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the specificity of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Dissertation on First Principles of Government (1795) in the context of the relations between liberalism and democracy in the transition from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century. The objective is to explain how Paine—as an English revolutionary and an actor, witness, and interpreter of the Age of Revolutions—developed a democratic vision during the period of the Convention initiated on 9 Thermidor (1794-1795) that distanced him from both Jacobin formulations and practices, and from legislations and speeches by Thermidorian deputies. To this end, we will also investigate other texts and letters by the author, and demonstrate his profound changes in relation to previous texts, such as Common Sense and Rights of Man. With this in mind, this text intends to open new perspectives regarding Paine’s work and its place in the history of political thought.1

“The pomp of courts and pride of kings

I prize above all earthly things;

I love my country; the king

Above all men his praise I sing:

The royal banners are displayed,

And may success the standard aid.

I fain would banish far from hence,

The Rights of Man and Common Sense;

Confusion to his odious reign,

That foe to princes, Thomas Paine!

Defeat and ruin seize the cause

Of France, its liberties and laws”.2

– Arthur O’Connell

Written and published in July 1795, the Dissertation on the First Principles of Government was the culmination of Thomas Paine’s (1737–1809) democratic theory, in which he advocates for universal (“non-census,” though still restricted to men) suffrage and criticizes its absence in the Thermidorian French Constitution, the third of the revolutionary period, enacted that same year.

At this point, Paine was a prominent figure in the Atlantic world through various writings, especially Common Sense (1776), the main pamphlet of the American Revolution, and Rights of Man (1791), a defense of the French Revolution against Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France.

No foreigner took part in the French Revolution as decisively and for such a prolonged period as Paine. Elected deputy for Pas-de-Calais, he was imprisoned by the Jacobin government in December 1793, along with deputy Anacharsis Cloots (of Prussian origin and Dutch descent), both under the justification of being foreigners. With the help of the American ambassador and future U.S. president James Monroe, Paine was released in November 1794. The unspoken reason for his imprisonment was his opposition to the execution of Louis XVI (although he was a republican, Paine was against the death penalty and advocated for the exile of the Bourbon king) and his closeness to Brissot and the Girondins.

After being released from prison and once again serving as a deputy, Paine distanced himself from the former Girondins (many of whom were now Thermidorians) by advocating for universal suffrage. Paine’s opposition to them was not new: it is worth noting his defense of the Republic in 1790, even before Robespierre. However, such criticism eased during the Jacobin period—resisting the Terror and the de-Christianization movement became paramount. Once the Jacobins were overthrown, the divide between Paine and the Thermidorians gained momentum, a decisive factor in his return to the United States in September 1802.

BEGINNINGS

Paine had first sailed to North America in 1775 with a political stance that was unclear, which we could describe as leveling (a reference to the Levellers during the English Civil War of 1642–1649) and censitary, whereby only those with leisure and financial autonomy could vote.4 4 In 1778, Paine wrote:

Likewise all servants in families; because their interest is in their master, and depending upon him in sickness and in health, and voluntarily withdrawing from taxation and public service of all kinds, they stand detached by choice from the common floor.

In that same letter, Paine, judging by Foner’s complete works, used the word democracy and democratical for the first time. At this point, however, he still viewed democracy in the pejorative sense commonly held, i.e., as a degenerate form of government: “Such a State will not only become impoverished, but defenceless, a temptation to its neighbors, and a sure prize to an invader.”5 This use, in the context of the debate over the independence of the 13 colonies, was intended to defend a constitutional government.

In the context of the French Revolution, Paine began to condemn property qualifications for voting. In Rights of Man (1791), a response to Edmund Burke’s text, Paine argued that voting should be as universal as taxation, a radical proposal in the English context, where nearly all adult men paid some form of indirect tax. Only in 1795, in the Dissertation on the First Principles of Government, did he openly defend universal suffrage. For this reason, Moncure Conway, who wrote the first well-founded biography of the author, stated that few pamphlets by Paine deserve more study.7

By the way, Rights of Man represented the second time—again, according to Foner’s complete works—that Paine used the words democracy and democratical, but this time in a positive sense: now, the notion of “democracy” was equivalent to a desirable, equal, representative government, one that was taking shape in the United States and France. The Dissertation, in turn, was the third and final time that the author used the term in his texts; in this case, although the idea of democracy is bolder, the word’s use is more restrained (it appears only twice in the text), as the author prefers the term “representative government” to refer to male universal suffrage, equality before the law, checks and balances, and human rights (between the two texts, there were Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, which, as we will see, likely explains the different uses and notions).

The terms “liberal” and “illiberal” appear much more frequently in Paine’s works (“liberalism,” in turn, is a term from the 19th century, as will be discussed). In most of Paine’s writings, the term appears in its common sense, referring to generosity (“my intentions were liberal, they were friendly.”8 Paine also described friendliness (the terms liberality and liberal sentiments are also frequent), or a specific type of education (such as liberal arts and sciences).

However, as we will see below, according to some recent studies, the term “liberal” underwent transformations in 18th-century Anglo-Scottish enlightenment thought. Paine’s works seem to follow this movement. The term began to appear in his works in a compound form—such as liberal ground, liberal cast, and liberal thinking—and was related to forms of noninterference and non-oppression.9 For example, in a letter to George Washington, Paine stated that trade between North America and France was founded on “most liberal principles, and calculated to give the greatest encouragement to the infant commerce of America.”10 Another letter of Paine’s, concerning the Constitution of Pennsylvania, expresses this transformation of the term well, as here the word liberal can be understood as “generosity,” but at the same time as “non-interference” and “non-oppression”:

It is the nature of freedom to be free… Freedom is the associate of innocence, not the companion of suspicion. She only requires to be cherished, not to be caged, and to be beloved, is, to her, to be protected. Her residence is in the undistinguished multitude of rich and poor, and a partisan to neither is the patroness of all (…) To engross her is to affront her, for, liberal herself, she must be liberally dealt with.11

Having made these preliminary observations, it is important to note that Dissertation on the First Principles of Government has never received the attention it deserves from historians. This absence is particularly evident among classic Paine scholars. Foner merely emphasized that the pamphlet addresses the issue of suffrage. Aldridge merely noted that he wrote the pamphlet in light of the “new constitution.”12 Vincent only highlighted Paine’s defense of bicameralism.13 Paine biographers John Keane and Craig Nelson simply stated that Paine defended universal suffrage.14 Mark Philp and Gregory Claeys, the two historians who have best studied Paine’s thought, were brief: the former surprisingly qualifies it as “a summary of Rights of Man (1791).”15 The latter merely notes its limited reception. Modesto Florenzano pointed out the pivotal place of the text in the discussion about liberalism and democracy; however, his study, as it is more concerned with other aspects of Paine’s life and work, did not focus on an in-depth analysis of this pamphlet.16

Currently, the English revolutionary has received a substantial amount of study, both for his role as an Atlantic revolutionary and for his position neither strictly Jacobin nor exactly Girondin. However, the Dissertation remains secondary in the most recent studies on the author. Mario Feit cites the text only three times to address the relationship between time and rights in Paine.17 J.C.D. Clark claims that it “has little to say about France.”18 Thus, Dissertation, a “milestone in Paine’s career,” has never received the attention it deserves.19 However, in addition to filling an important gap, its analysis will reveal significant shifts in relation to Paine’s more well-known texts Common Sense and Rights of Man, and, as a result, will showcase facets of the author that have been little discussed, which may strengthen Paine’s place as a political thinker and, contrary to what Clark stated, an interpreter of the French Revolution.

To fulfill this purpose, this text will be structured in three parts: first, we will examine the publication of Dissertation within its context; second, we will analyze its fundamental ideas; and finally, the pamphlet will be considered within the political/philosophical debates of its time. The text, like all of Paine’s political works, is deeply intertwined with the revolutionary axis of London-Paris-Philadelphia, and can only be understood within these dialogues (although it also holds importance in other spaces such as Ireland and the Netherlands).

THE THERMIDORIAN LIBERALISM

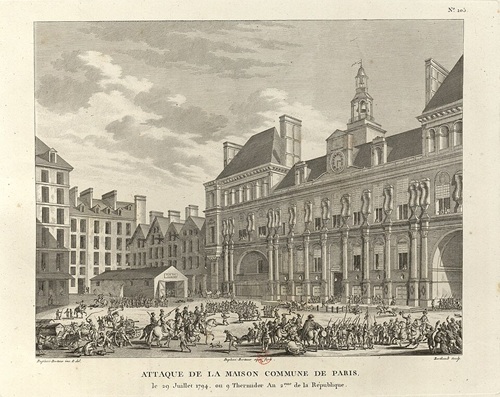

Paine began writing Dissertation with the Dutch Republic in mind. However, after the fall of the Jacobin government on July 27, 1794 (9 Thermidor), the text was directed at the Thermidorian National Convention, as it discussed the Constitution of Year III. The Thermidorian Convention, which followed the Jacobin government, lasted fifteen months, until October 1795, when it gave way to the Directory. The day after 9 Thermidor, the deputies opposed the old slogan, “Terror on the agenda,” with a new counter-slogan, “Justice on the agenda!”20 There was a new rallying cry, “restore social order in place of the chaos of revolutions.”21 Therefore, it was a government that sought to end the Revolution and justified itself negatively: neither Terror nor monarchy.

The new declaration of rights replaced “men are born free and equal” with “equality consists in the law being the same for all,” just as the right to property, which had not been defined in 1789, was specified: “property is the right to enjoy and dispose of one’s goods, income, the fruits of one’s labor, and industry.”22 While still considering the Caribbean world, the Convention maintained the abolition of slavery and guaranteed citizenship to Haitians.

After the occupation of the Convention by representatives of the sections linked to the sansculottes, demanding bread and freedom, the Assembly appointed, in April 1795, an eleven-member commission to draft a new Constitution. The report was delivered on June 23. A well-known speech by the reporter Boissy d’Anglais is illustrative:

We must be governed by the best men; and these are the most educated and the most interested in maintaining the law. However, with few exceptions, such men can only be found among the holders of property who, consequently, are tied to their country, the laws that protect their property, and the social peace that preserves them. A country governed by men of property is an authentically civil society; a country where men without property govern is in a state of nature.23

On June 6, 1795, Paine, alarmed by the direction the Convention was taking, wrote to Deputy Thibaudeau emphasizing that reverting to a censitary system would justify new rebellions: “How could we imagine that recruits willing to die for the cause of equality tomorrow would agree to sacrifice their lives for a government that had stripped them of their fundamental natural rights?”24 Paine then published the pamphlet Dissertation on First Principles of Government on July 4, 1795. Three days later, for the first time since the fall of the Jacobins and the last time in his life, Paine took the floor at the Convention. The brief speech at the French National Convention is transcribed in The Constitution of 1795.

[the] Constitution which has been presented to you is not consistent with the grand object of the Revolution, nor congenial to the sentiments of the individuals who accomplished it…The first article, for instance, of the political state of citizens (v. Title ii. of the Constitution), says: ‘Every man born and resident in France, who, being twenty-one Years of age, has inscribed his name on the civic register of his canton, and who has lived afterwards one year on the territory of the Republic, and who pays any direct contribution whatever, real or personal, is a French citizen.’

I might here ask, if those only who come under the above description are to be considered as citizens, what designation do you mean to give the rest of the people ? I allude to that portion of the people on whom the principal part of the labor falls, and on whom the weight of indirect taxation will in the event chiefly press. In the structure of the social fabric this class of people are infinitely superior to that privileged order whose only qualification is their wealth or territorial possessions. For what is trade without merchants? What is land without cultivation? And what is the produce of the land without manufactures?25

One of the more opportunistic traits of this Constitution was the “two-thirds decree,” which aimed to prevent monarchists (encouraged by the self-proclaimed Louis XVIII) from forming a majority in the assembly: in the first elections, two-thirds of the future deputies had to be chosen from among the convention members whose mandates were about to expire. Despite the fall of the Jacobins, the “logic of public salvation” remained, according to which the Revolution should be defended, even at the cost of transgressing its principles.26 By the way, two important leaders, the former supporters of the Jacobin government, Tallien and Billayd-Varenne, openly spoke of maintaining terror against traitors.27

On October 26, the Convention dissolved itself and, according to Sieyés’s proposal for the new Constitution, was replaced by the Council of Five Hundred (tasked with drafting laws) and the Council of Ancients (tasked with voting on them, being half as numerous, with members having to be over forty years old). The executive power (the five members of the Directory) was elected by the two branches of the legislature: unlike the other two revolutionary constitutions, bicameralism was established here, under strong American influence.28 The Directory would dismiss local administration members without appeal, direct diplomacy, and could issue orders for arrests; in these respects, the Consulate was not a rupture but an intensification of the previous government.29 In October, the election of the Directory took place; Paine, who never ran again, became an ordinary citizen.

That said, it is essential to acknowledge that, during the Thermidorian period, a version of French liberalism emerged, which we will call Thermidorian liberalism.30 This version consisted of the idea that it was impossible to reconcile the participation of the population in the political process (democratic principles) with the protection of individual rights and liberties (liberal principles) in the post-Jacobin context. Therefore, in his speech of July 20, 1795, Sieyès criticized “the unlimited sovereignty that the Montagnards had attributed to the people, based on the model of the sovereignty of the king in the Old Regime”—he refers, incidentally, to the Jacobin regime as ré-totale, in contrast to ré-publique.31 It is clear that the tension between individual freedoms and democracy—frequently associated with the 1820s— was already present in the Thermidorian Convention.

With these considerations in mind, it is possible to highlight the problem that is at the heart of this text, which is to explain how Paine, a Thermidorian deputy openly anti-Jacobin and concerned with individual liberties and the limits of the state, positioned himself at this moment.

DISSERTATION ON THE FIRST PRINCIPLES OF GOVERNMENT

The pamphlet Dissertation on the First Principles of Government presents a clear and well-structured argument, aiming to introduce the author’s most radical point: private property cannot be a natural right that overrides others and, therefore, should not be used as a criterion for voting rights. The pamphlet is divided into five parts: in the first, Paine expresses his belief in the centrality of politics; in the second, he presents three arguments against hereditary governments, discussing his conceptions of nation, social contract, and popular sovereignty; in the third, he addresses representative government, emphasizing the irrationality of property-based voting; in the fourth, he defends bicameralism (a significant shift from his ideas in Common Sense and a departure from the antifederalists ), explains the role of the executive power and the rotation of power, and reaffirms the importance of education; finally, he concludes with a defense of tolerance.32

Paine begins by stating that there is no “subject more interesting to every man than the subjects of government. His security, be he rich or poor, and in a great measure his prosperity, are connected therewith.”33 His goal, therefore, is to study and perfect what he calls the “science of government,” which, of all things, is the least mysterious and the easiest to understand.34 From there, he moves away from classical subdivisions and proposes that:

The primary divisions are but two: First, government by election and representation. Secondly, government by hereditary succession.

(…) As to that equivocal thing called mixed government, such as the late Government of Holland, and the present Government of England, it does not make an exception to the general rule, because the parts separately considered are either representative or hereditary.35

The revolutions spreading across Europe are, ultimately, “a conflict between the representative system founded on the rights of the people, and the hereditary system founded in usurpation.”36 Thus, aristocracy, oligarchy, and monarchy are distinct expressions of the same hereditary system, which must be rejected. Paine also rejects “simple democracy” (direct democracy), considering it impractical: “the only system of government consistent with principle, where simple democracy is impracticable, is the representative system.”37

Paine was a key figure in the Thirteen Colonies, transforming republicanism from an ethical ideal and “way of life,” as it was seen in the mid-1700s, into a practicable and desirable political regime.38 At this point, he reaffirms his well-known departure from part of the 18th-century republican language by conceiving the English government not as mixed and balanced, but as aristocratic: “It is certain,” Paine wrote to Condorcet, “that certain places, such as Holland, Bern, Genoa, Venice, etc., which are called republics, do not deserve such a designation (…) for they are in a condition of absolute servitude to aristocracy.”39

Thus, Paine proceeds to discuss hereditary governments: “there is not a problem in Euclid more mathematically true than that hereditary government has not a right to exist.”40 He then lists three arguments against hereditary rule, all of a temporal nature: the first concerns the succession of governments; the second, their origins; and the third, the eternity of rights.

Hereditary government is contrary to reason because, by its nature, it is susceptible to falling into the hands of a minor or a fool.41 If the uncertainty of succession speaks against hereditary governments, the same can be said about their origins: hereditary government cannot begin because no man or family is above others. “If it had no right to begin,” Paine says, “it had no right to continue,” for:

The right which any man or any family had to set itself up at first to govern a nation, and to establish itself hereditarily, was no other than the right which Robespierre had to do the same thing in France. If he had none, they had none. If they had any, he had as much; for it is impossible to discover superiority of right in any family, by virtue of which hereditary government could begin. The Capets, the Guelphs, the Robespierres, the Marats, are all on the same standing as to the question of right. It belongs exclusively to none.42

In this regard, Robespierre’s power resembles the despotism of the Old Regime more than democracy. Unlike many liberals of the early 19th century, Paine did not see Jacobinism as an inherent danger to the egalitarian impulse of democracy, nor did he conceive liberty as an aristocratic stronghold, but precisely the opposite.

Hereditary government is also inconsistent in considering the relationship between time and rights: even if a government began illegitimately, would its usurpation become a right through the authority of time? The answer is negative in both directions: the present generations have no duty to submit to the men of the past (as he had already stated in Rights of Man), nor do they have the right to subjugate future generations. Rights are timeless and meta-historical and, therefore, universal in time and space: “Time with respect to principles is an eternal now: it has no operation upon them: it changes nothing of their nature and qualities.”43 It is up to the living to make politics, so the injustice that began a thousand years ago is as unjust as if it began today; and the right that originates today is as just as if it had been sanctioned a thousand years ago.

The notion that time does not create any form of right, reason, or authority is what definitively separates Paine from the ideas of Burke and those known as British conservatives. The historian Anthony Quinton describes, British conservatism in the 18th and 19th centuries as aiming to preserve the historical arrangement of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89, which encompassed three doctrines: the belief that political wisdom is historical and collective, residing in time (traditionalism); the belief that society is a whole, not just the sum of its parts (organicism); and the distrust of theory when applied to public life (political skepticism).44

For Paine, on the other hand, any nation that enacts an irrevocable law or tradition would be betraying, at once, the right of every minor in the nation and the rights of future generations: “The rights of minors are as sacred as the rights of the aged.”45 Thus, since minors and future generations are bearers of rights, any law that violates these groups is illegitimate. Legal authority (that is, the power to elect representatives and formulate laws), for Paine, rests on the consent of living men over 21 years of age; however, groups deprived of legal authority are not deprived of rights: “A nation, though continually existing, is continually in a state of renewal and succession. It is never stationary. Every day produces new births, carries minors forward to maturity, and old persons from the stage.46 In this ever running flood of generations there is no part superior in authority to another.”47

Thus, if it is evident that when a family establishes itself in power, we have a form of unquestionable despotism, it would be equally despotic when a nation consents to establish a regime with hereditary powers. The principle of consent as a source of legitimacy is taken to its ultimate consequences and extended to minors and those yet to be born: If the current generation, or any other, is willing to be enslaved, that does not diminish the right of the next generation to be free.

For Paine, including minors and future generations in the concept of the people and, consequently, protecting them by law, would prevent democracy from turning into tyranny; and, therefore, in Paine, “the subject of democracy must be understood as a subject that is both juridical (the people of citizenvoters) and historical (the nation that binds the memory and promise of a shared future).”48 However, democracy is historical precisely because it encompasses timeless human values and rights—the commitment to future generations and freedom from past generations is due to this unbreakable bond that would unite the living and the dead, which, contrary to what Burke and conservatives think, is not historical.

That said, democracy in Paine is a prolonged exercise of commitment, often tacit. It is not, therefore, a plebiscitary democracy in the sense of consulting the people on all decisions, or a “permanent revolution,” in the sense of a clean slate of political organization and a total reformulation of institutions, laws, and customs with each generation; but, as he stated in Rights of Man, the idea that “A law not repealed continues in force, not because it cannot be repealed, but because it is not repealed; and the non-repealing passes for consent.”49 Therefore, Himmelfarb seems to exaggerate when she says that: “The political revolution called for in Rights of Man was a genuine revolution that required the abolition of all the heritage of the past (..,) and inaugurated a kind of ‘permanent revolution’in which each generation would create its own laws and institutions.”50

However, it is important to note that, in the text, the author does not envision the possibility of granting women the right to vote, whose exclusion is not even discussed. In contrast to hereditary government, in representative government (in Rights of Man, he had already observed that direct democracy would only be feasible in small territories), there is no problem of origins, as it is not anchored in conquest or usurpation, but in natural rights: “Man is himself the origin and the evidence of the right. It appertains to him in right of his existence, and his person is the title deed.”51

Property-based voting, therefore, would produce a new kind of aristocracy, as a despotism installed within representative government. Private property, when used to strip others of their rights, becomes a privilege and becomes illegitimate:

“Personal rights, of which the right of voting for representatives is one, are a species of property of the most sacred kind: and he that would employ his pecuniary property, or presume upon the influence it gives him, to dispossess or rob another of his property or rights, uses that pecuniary property as he would use fire-arms, and merits to have it taken from him.”52

If, in nature, “all men are equal in rights, but they are not equal in power,” the institution of civil society aims at an “equalization of powers that shall be parallel to, and a guarantee of, the equality of rights.”53 While nature and civil society are spaces of inequality, political society is the space of equality; thus, democracy, inseparable from the idea of rights, guarantees a field of negotiation and compromise, creating the possibility of defending the poor against the rich and everyone against the state.

The inequality of rights is created by a maneuver of one part of the community to deprive the other part of its rights. Every time an article of a Constitution or a law is created in which the right to elect or be elected belongs exclusively to people who own property, whether small or large, it is a maneuver by those who possess such property to exclude those who do not: “it is dangerous and impolitic, sometimes ridiculous, and always unjust to make property the criterion of the right of voting.”54

Subjugating the freedom to vote to property relegates the right to choose representatives to irrelevance. Hence the absurdity of subordinating the freedom to vote to property, which, in the end, ties the right to things or animals:

“When a broodmare shall fortunately produce a foal or a mule that, by being worth the sum in question, shall convey to its owner the right of voting, or by its death take it from him, in whom does the origin of such a right exist? Is it in the man, or in the mule? When we consider how many ways property may be acquired without merit, and lost without crime, we ought to spurn the idea of making it a criterion of rights.”55

Property-based suffrage, moreover, can link voting to crime, since, as the author reminds us, it is possible to acquire income through theft; in this sense, a crime could create rights. Furthermore, since, in a democracy, one can only lose their rights through a crime, the exclusion of the right to vote would create a “stigma” on those who do not own property, as if they were delinquents: Wealth is not proof of moral character, nor is poverty proof of its absence. “On the contrary, wealth is often the presumptive evidence of dishonesty; and poverty the negative evidence of innocence.”56

The worst kind of government, Paine argues, is one in which deliberations and decisions are subject to the passion of a single individual. When the legislature is concentrated in one body, it resembles such an individual. Therefore, representation should be divided into two elected bodies, separated by lot. Such separation of powers did not actually occur in England, as the House of Lords, lacking representativeness, relates to the legislative power as a “member of the human body and an ulcerated wen.”57

The executive and judicial powers, on the other hand, would both exercise a mechanical function: “The former [the legislative] corresponds to the intellectual faculties of the human mind which reasons and determines what shall be done; the second [the executive and judicial], to the mechanical powers of the human body that puts that determination into practise.”58 Magistrates, thus, are mere delegates, “for it is impossible to conceive the idea of two sovereignties, a sovereignty to will and a sovereignty to act.”59 Nevertheless, the defense of the separation of powers remains intact to the unity of sovereignty.

Similarly, Paine continues, power should never be left in the hands of someone for too long, as the “inconveniences that may be supposed to accompany frequent changes are less to be feared than the danger that arises from long continuance.”60

It is precisely these checks and balances that faded during the Jacobin period. Paine, then, distinguishes the methods used “to defeat despotism” and the procedures “to be employed after the defeat of despotism,” which are the “means to preserve liberty.”61

In the first case, necessity predominates, calling for insurrection and violence, since, in a despotic regime, legal means for change are barred. In the second case, respect, pacifism, and debate predominate, so that: “Time and reason must cooperate with each other to the final establishment of any principle; and therefore those who may happen to be first convinced [of the importance of rights have not a right to persecute others, on whom conviction operates more slowly. The moral principle of revolutions is to instruct, not to destroy.”62

Therefore, the government following a revolution should not be a revolutionary government. By revolutionary government, Paine means—and this is the heart of his interpretation of Jacobinism—a regime that maintains the use of the means that were necessary to overthrow the previous regime:

“Had a constitution been established two years ago (as ought to have been done), the violences that have since desolated France and injured the character of the Revolution, would, in my opinion, have been prevented. The nation would then have had a bond of union, and Every individual would have known the line of conduct he was to follow. But, instead of this, a revolutionary government, a thing without either principle or authority, was substituted in its place; virtue and crime depended upon accident; and that which was patriotism one day became treason the next (…) But in the absence of a constitution, men look entirely to party; and instead of principle governing party party governs principle.63

In summary, Paine aligns himself with the predominant concern of the Thermidorian deputies, namely, to “end the Revolution.” However, the Thermidorians, by removing the right to vote from the population, resemble the Jacobins in despotism and end up justifying new rebellions. In a way, although Paine rejects, as we have seen, British conservatism and the Thermidorian anti-democratic perspective, he does not fail to aspire to a kind of liberal-democratic status quo that institutionalizes revolutionary measures and ideas, abolishing the revolutionary government and leaving no other path for change but legal means. Thus, he concludes his pamphlet with one of his most expressive phrases:

“An avidity to punish is always dangerous to liberty. It leads men to stretch, to misinterpret, and to misapply even the best of laws. He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression; for if he violates this duty he establishes a precedent that will reach to himself.”64

However, a note is in order: democracy, to Paine, will be incomplete if we think only of its political dimension. Its religious and social dimensions remain. At the time of the Dissertation, Paine wrote, in 1793, The Age of Reason, in which he presented revealed religions as anti-democratic, as they reinforced the authority of institutions and excluded the illiterate (who could not read the Scriptures) and those who had no opportunity to come into contact with the true religion from Truth and Salvation. Thus, deism would be the truly democratic religion, equally accessible to all human beings, regardless of where they were born or their level of education. In this text, Paine also discussed the importance of religions protecting animals other than humans. In 1797, he published Agrarian Justice, in which he argued that democracy would only be realized when everyone had minimum social conditions of existence and basic opportunities guaranteed—hence his idea of a state-guaranteed income for all citizens from a fund constituted by a universal tax on inheritances (at a rate of ten percent), a reform proposal that should serve as an alternative to the Agrarian Law. A treatment of these other dimensions of democracy in Paine will be done on another occasion. It is noteworthy, however, that Paine is far from reducing the democratic ideal to voting or mere political institutional mechanisms.

In the meantime, a question arises: does Paine’s discourse, by defining itself as democratic, align in any way with the Robespierrist projects? There are several convergences between Paine and Robespierre: both converge in their critique of the Agrarian Law and in their defense of some form of Progressive Tax. The most glaring divergences between Paine and Robespierre occur, in this sense, in the political field. It should be noted that the Jacobin group did not have a ready-made program, as is sometimes assumed (moreover, there were no political parties as we understand them today), but an ideology always modified by revolutionary circumstances and which can only be qualified based on its speeches and practices. The same happened, by the way, with Robespierre himself, who oscillated in his defense of direct democracy (1789-1792), representative government (from the end of 1792), the importance of primary assemblies (changes of opinion are verified in September 1792), and the Constitution of 1791.65

In this sense, we refer here to Robespierre during the months he was part of the collegium of the Committee of Public Safety. At first glance, Robespierre agreed with Paine, stating that property-based voting would create a new aristocracy, that of “the rich.”66 However, although the Jacobin Constitution guaranteed universal suffrage, it did not put it into practice, as he stated in February 1794, it is necessary to “end the war of liberty against tyranny.”67 To understand such measures, Robespierre said, one only needed to “consult the circumstances,” a thesis reproduced both by the Jacobins and by part of historiography in the 19th and 20th centuries.68

Robespierre then accused those who called themselves moderates of being traitors (seen by him, in fact, as “moderantists”), for they desired a revolution “subordinated to pre-existing norms.”69 Similarly, although Robespierre philosophically opposed the death penalty, he emphasized that a revolutionary government would require extreme measures: “The government owes the good citizens all national protection; to the enemies of the people, it owes nothing but death.”70 Therefore, the opposition to the idea of a revolutionary government, as seen in the analysis of the Dissertation, is the crux of the disagreement between Paine and Robespierre—the tension “necessity/liberty,” capable of turning democracy into despotism, is rejected by the English thinker.71

It should be noted that, while Paine distances himself from the “thesis of circumstances” (usually associated with Marxist or Jacobin historiography), he also does not align with the notion, defended by a certain “liberal” historiography, that the terror was a logical conclusion of the Revolution, as suggested by Furet and Ozouf, or that violence was “the driving force” of the revolutionary process.72 The place of the Dissertation in the early interpretations of Jacobinism, therefore, lies in the reading of the terror as a deviation from the Revolution and a reminiscence of the despotism of the Old Regime (I hope that, thus, it is demonstrated that Paine’s text, contrary to what Clark pointed out, has something to tell us about the French Revolution).

A DEMOCRATIC LIBERALISM

In this sense, the moderate stance and the “preexisting norms” referred to by Robespierre touch precisely on what can be seen, from a certain perspective, as the liberal character of Paine’s thought—a key element that separates the positions of the two protagonists.

The earliest uses of the word liberal in reference to the ideas embodied in the revolutions of 1776- 1848 — no longer in relation to a specific education or vague idea of amicability (Simpkin, Weiner and Proffitt, 1989) — date back to early 19th century Spain. In the context of the Cádiz Constitution, the liberales referred to those opposed to representative government and the Constitution as serviles (servants). For example, in the magazine El Español, in 1811, Blanco White referred to the constitutionalists as liberales in reference to the impact of the French Revolution on Europe. In a letter to Jovellanos in 1809, the French general Sebastiani referred to “vuestras ideas liberales” (your liberal ideas) in speaking of the ideas of tolerance and equality that should lead the Spanish to ally with Napoleon against the Spanish monarchy.73 In 1813, in the Diario Militar, Politico y Mercantil de Tarragona, we find the first known use of the word liberalismo: “if liberalism is (…) to desacralize a people, I detest being a liberal.”74

That being said, it should be noted that in the realm of political ideas, the emergence of a specific denomination may not be understood exactly as an act of foundation, but as a gain in awareness (which is also a form of producing new meanings and possibilities for thought) regarding a situation that already possesses some degree of crystallization. In the case of liberalism, this crystallization process in the decades preceding 1820 is well-documented, as recent studies show. However, it is equally true that, in the absence of such a denomination, there is a risk of seeing in what has been established earlier a degree of coherence that might not actually exist.75

In this sense—and considering the enormous variety of liberalisms throughout history—rather than thinking of liberalism as a doctrine, it seems more appropriate to see it as a field, or a vast space of thought with some identifiable degree of kinship, within which there is room for the creation and proposal of the most varied positions. As a space of thought, liberalism has limits, which defines the objective existence of this field and at the same time distances us from overly essentialist, dogmatic, or normative positions.

Starting from these premises, we support the possibility of agreeing on the existence of a classical liberal language in the second half of the 18th century, prior to the actual emergence of the term liberalism, but which would share degrees of kinship with 19th century ideas. The elements and limits of this language would include, namely, the defense of natural rights, contractarianism, opposition to traditional privileges and corporate monopolies, the idea of a state of nature, and the defense of checks and balances against the excesses of the state and society.

It is important to note, however, that such elements are often scattered (after all, it is only the emergence of the word liberalism that would attempt to create some unity and coherence) and do not appear uncontested in any one author. Likewise, they are sensitive to other discourses, especially republican ones.

That said, to what extent is it plausible to say that classical liberalism is democratic? In other words, how did authors of the time deal with the issue of limiting and distributing power at the same time?

The word democracy in the 18th century was rarely used in a favorable sense. Marquis d’Argenson (1694- 1757), in his Considérations sur le gouvernement de la France (1764), was one of the first to use it referring to political equality and rights (thus favored by the monarchy), rather than self-government. However, the terms Démocrat and Aristocrate did not appear in France and America before the revolutions—its first uses date back to the Dutch Revolution (1784-1787) and the Belgian Revolution (1789-1791).

Throughout the Age of Revolutions, the term gained greater circulation, being associated with equal rights, popular government, or the primacy of local assemblies. For instance, Barnave referred to an “era of democratic revolutions” to characterize the period in which he lived. The uses indicate a fundamental transformation: in addition to being a form of government (democracy), the term also referred to agency (democrat), adjectivation (democratic), and actions (democratize). Thus, democracy meant both a form of government and a practice aimed at greater equality.

Indeed, the three most frequent and favorable uses of the word democracy during the period were made by Robespierre (which, by the way, would later be a key reason for the word having a negative connotation in the following decades), by the bishop of Imola and future Pope Pius VII, and, of course, by Thomas Paine. The first time Paine explicitly used the term was, as seen, in the second half of Rights of Man, where he referred to democracy as a form, as well as a public principle of government, advocating for representation as a means of its realization.

Nevertheless, at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century, the field we call classical liberalism and democratic language in both Europe and North America were mismatched. The dominant position excluded from voting workers, salaried individuals, beggars, as well as women and children, as they were assumed to depend on the will of others. Property was understood by many as the means to link self-interest with societal interest, thereby ensuring access to political power.76 Even in the 17th century, Locke, a highly influential author for this generation, believed that non-property owners lacked “full interest” in the benefit of society and should, therefore, be excluded from voting.77 Jefferson, although reflecting critically on land and inheritance, viewed the condition for the existence of democracy as a society in which everyone was economically independent; like the Federalists Jay, Madison, and Hamilton, he linked voting to property.78 Burke believed that society could not be governed by an “abstract principle” like popular voting.79 Madame de Stäel, who attacked the Dissertation defended a more limited suffrage than that of the 1795 Constitution.80 Benjamin Constant argued that “only property grants men the capacity to exercise democratic rights.”81 After the French Revolution, the so-called doctrinaire liberals concerned with the “tyranny of the majority” argued, as Tocqueville would later, for the need for firm dams against the democratic flood.

Macpherson argued that the utilitarians Bentham and James Mill, the father of Stuart Mill, were the first democratic liberals. However, Bentham, in 1817, said that certain exclusions should be made, at least for a certain time and for the purposes of gradual experimentation.82 James Mill, in turn, argued that it would be prudent to exclude women, men under 40, and the poorer classes from voting. Stuart Mill, a proponent of women’s suffrage in Parliament, excluded from the franchise those who did not pay taxes, lived off charity, and argued that the more enlightened should have the right to plural voting.83

A more recent historiography of liberalism brings new light to Paine’s work. In Liberalism: A Very Short Introduction, Michael Freeden reaffirms that until the 19th century, liberalism and democracy were disconnected for two correlated reasons: fear of the “tyranny of the majority” and the “ignorance of the people” (themes that were addressed by Paine).84 In addition, three recent handbooks on the history of liberalism bear mention. First is Edmund Fawcett’s Liberalism.84 Fawcett’s text does not reference Paine’s work, but James Traub’s What Was Liberalism briefly mentions Paine as someone who endorsed the revolutionary violence of the crowd.85 After this characterization, Traub credits Madison with a view closer to ours on liberalism for considering the solution to the tyranny of the majority within, and not outside, democracy.86

However, Madison’s democracy, as shown, was less inclusive in social and political terms than Paine’s. In The Federalist (No. 10, 1787), the Virginian, contrary to Paine, made an effort to dissociate republic and democracy: “democracies have always been the scene of disturbances and controversies, have proven incapable of ensuring personal security or property rights, and in general, have been as brief in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.”87 Finally, Helena Rosenblatt’s The Lost History of Liberalism refers to Paine in the chapter discussing the relationships between liberalism and the French Revolution.88 The author makes an observation, which we believe is correct about Paine, arguing that, for him, the problem was not whether an individual or group was liberal, but whether the fundamental principles of a nation were. This observation is based on the distinction between “people” and “principles” made in Rights of Man, in his debate with Edmund Burke.

Thus, it is possible to affirm that Thomas Paine was one of the first to present the formula of democratic liberalism, advocating a specific notion of equality and a broader suffrage than was common at the time, while still maintaining the foundation of natural rights, contract theory, free trade, and checks and balances. This combination, as seen, can only be understood in light of the history of the French Revolution and sets him apart from many of the positions that were overlooked by historians.

In Paine, the remedy for the ills of democracy and the protection of individual liberties does not lie in limited suffrage or repression, but in the refinement of democracy, understood as a limit to authoritarianism and greater political participation, coupled with a broader enlightenment of the population. The way to avoid the tyranny of the majority is not through restricting the vote, but by incorporating the lesser groups and future generations into the notion of the people, thus expanding the notion of popular sovereignty. The richness of these discussions in which Paine’s thought is embedded is, finally, symptomatic of the great laboratory of political experiments and ideas that constituted the Age of Revolutions.

CONCLUSION

The Dissertation is a seminal text in understanding the changes in Paine’s thought throughout the French Revolution and enlightening in regard to the problems and debates raised during the Thermidorian period, which became fundamental in the first half of the 19th century. The little attention the text has received from Paine is unfortunate. The text thus expresses two lesser-known facets of Paine: on one hand, his concern with the excesses of central power and the possibilities of a majority dictatorship, contrary to what was emphasized in most of his earlier texts; on the other hand, an openly democratic stance, which, although underlying texts such as Rights of Man, takes its most expressive form in this pamphlet—therefore, at once, a more democratic Paine, but also concerned with the potential excesses of such democracy, a rather distinct image from the Paine of Common Sense, who supported unicameralism and was hesitant about universal suffrage. The formulation of property undoubtedly as a right, but as a right less important than life or liberty, lies at the heart of his insubordination against inequalities. These changes, as attempted to be shown, are strongly linked to the Jacobin phenomenon itself and the practices of the Thermidorian government, which reveals the relevance of Paine studies for understanding the period.

Nevertheless, it is clear that Paine had his own contradictions. What, for some, is an ideological inconsistency and, for others, true political realism (since the enemies did not act within the rules of the democratic game and had international connections), he supported the coup of 18 Fructidor of Year IV, September 4, 1797, when the Directory annulled the March elections that had given the realists a majority. The Fructidor coup reinforced an authoritarian path that culminated in the 18 Brumaire coup of 1799. Although he rejected Robespierre’s “principle of circumstances” and “the logic of Public Salvation,” Paine did not, therefore, refrain from using the same tactic. In any case, Paine never denied the need for revolutionary violence, as expressed in his well-known break with the Quakers in 1776—only that, in the Jacobin period, he did not see such a need. The author also encouraged the Directory to invade Great Britain and, along with Bonaparte, devised a detailed plan for the French troops’ entry into the island and launched the idea of a vast popular subscription to finance the operation.89

Moreover, the Dissertation occupies a fundamental place in the history of liberal thought, as I have attempted to show. I believe that today, the liberal field faces three primary challenges, namely: how to prevent inequality, in its most acute forms, from being harmful to life and liberty without resorting to authoritarian solutions? How to ensure that the purported universalism of liberty and human rights coexists with the contradictory diversity of thoughts, beliefs, and forms of existence? How, without resorting to some form of elitist dirigisme, to prevent men, by their own disposition, from renouncing democracy in favor of dictatorial regimes? The discussions about these issues can be enriched if Paine’s perspectives are considered.

- This paper was originally published in 2021 in the Revista de História of University of São Paulo (USP) under the title “Thomas Paine e a Revolução Francesa: Entre o Liberalismo e a Democracia (1794-1795).” The generosity of the Revista de História in allowing the publication of this text in English is greatly appreciated.

- This poem was distributed by the Irishman Arthur O’Connell in 1798. Apparently, it was a rebuttal to Thomas Paine. However, if the first verse of the first stanza is interwoven with the first verse of the second stanza, as well as the second, the third, and so on, the result would be a subversive pamphlet, which was O’Connell’s real objective. Paine was an honorary member of the Society of United Irishmen, which advocated for parliamentary reform (Hitchens, 2007).

- On the leveling position, see Crawford Brough Macpherson, Democratic Theory: Essays in Retrieval. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973, and more recently, Taylor; Tapsell, 2013.

- Philip S. Foner, ed., The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, I, (New York: The Citadel Press, 1945), 287.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 277

- Moncure Daniel Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, (New York: Arno Press, 1977), 161-162.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 1238

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 61, 127, 237.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 715.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 284.

- Alfred Owen Aldridge, Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine, (New York: J. P. Lippincott Company, 1959). 225.

- Bernard Vincent, Thomas Paine: O Revolucionário da Liberdade. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1989.

- John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life. London: Bloomsbury, 1995; and Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution and the Birth of Modern Nations, (New York: Viking Penguin, 2006

- Philp, Mark. Paine. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 21; and Gregory Claeys, Thomas Paine: Social and Political Thought, (Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989).

- Modesto Florenzano, Começar o mundo de novo: Thomas Paine e outros estudos. Tese (livre-docência:Universidade de São Paulo, 1999).

- J.C.D. Clark, Thomas Paine: Britain, America, and France in the Age of Enlightenment and Revolution. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) 359-362.

- Modesto Florenzano, Começar o mundo de novo: Thomas Paine e outros estudos. Tese (livre-docência:Universidade de São Paulo, 1999).

- Carine Lounissi, Thomas Paine and the French Revolution. (Cham: Springer, 2018), 235

- Bronislaw Baczko, Comment sortir de la Terreur, (Paris: Gallimard, 1989), 421.

- Albert Soboul, A Revolução Francesa. (São Paulo: Difel, 2003), 108.

- Jean-Clément Martin, La Revolución Francesa: Una Nueva Historia. (Barcelona: Crítica, 2019), 447.

- Jeremy Popkin, A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution,(London: Hachette UK, 2019), 448. 21 Foner, II, pg. 968.

- Bernard Vincent, Thomas Paine: O Revolucionário da Liberdade. (São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1989), 258.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 590.

- François Furet, e Mona Ozouf, eds. Dicionário Crítico da Revolução Francesa. (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Fronteira, 1988), 50.

- Richard Bienvenu, The Ninth of Thermidor: The Fall of Robespierre. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968).

- Nora citation is missing, 1988.

- Soubel, A Revolução Francesa.

- Baczko, Comment sortir de la Terreur, 429.

- Popkin, A New World Begins, 420, 450.

- It is important to remember that, at the time of the publication of Common Sense, John Adams stated that Paine’s pamphlet was “o democratical, without any restraint or even an Attempt at any Equilibrium or Counterpoise, that it must produce confusion and every Evil Work” (Bailyn, 2003, p. 262). During the French Revolution, in a text likely written in 1791, Paine wrote an interesting and little-known pamphlet, organized around questions and answers, called Answer to Four Questions on the Legislative and Executive Powers. The first of the four questions (which by itself is representative of the urgency of the issue) concerns the possible abuses of the executive and legislative powers. Paine is then emphatic in stating that, “If the legislative and executive powers be regarded as springing from the same source, the nation, and as having as their object the nation’s weal by such a distribution of its authority, it will be difficult to foresee any contingency in which one power could derive advantage from overbalancing the other” (Foner, 1945, p. 522). Therefore, there is an important shift in Paine’s thinking, which occurs in light of the Jacobin practices, namely, the greater importance of checks and balances in political structures.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 571.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 571.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 571-572

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 572.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 584.

- Franco Venturi, Utopia e reforma no Iluminismo. (São Paulo: Edusc, 2003).

- Jonathan Israel, A Revolução das Luzes: O Iluminismo Radical e as Origens Intelectuais da Democracia Moderna. São Paulo: Edipro, 2013.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 572-573.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 573.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 574.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 574.

- Anthony Quinton, The Politics of Imperfection: The Religious and Secular Traditions of Conservative Thought in England from Hooker to Oakeshott. (London: Faber, 1978).

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 574.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 575.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 575.

- Pierre Rosanvallon, El momento Guizot: el liberalismo doctrinario entre la Restauración y la Revolución de 1848/Le moment Guizot, (Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2015), 90.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 254

- Gertrude Himmelfarb, La Idea de Pobreza: Inglaterra a Principios de la Era Industrial, (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1988), 116.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 577.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 577.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 583.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 579

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 579

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 579

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 586.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 586.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 586.

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 587

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 587

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 587

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 587-588

- Foner, The Complete Writings, 588.

- Furet, François, e Mona Ozouf, eds. Dicionário Crítico da Revolução Francesa. (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Fronteira, 1988), 320.

- Žižek, Slavoj. Robespierre: Virtude e Terror. (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Zahar, 2007), 53.

- Žižek, Robespierre, 144.

- Žižek, Robespierre, 146

- Žižek, Robespierre, 12.

- Žižek, Robespierre, 12.

- Ruy Fausto, “Em torno da pré-história intelectual do totalitarismo igualitarista.” Lua Nova, no. 75 (2008): 143–98.

- Schama, Simon. Cidadãos: Uma Crônica da Revolução Francesa. (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989)689.

- Gaspar Melchor Jovellanos, Obras Completas, Vol 1, (Madrid: Atlas, 1963), 590-591.

- Vicente Lloréns, “Sobre la aparición de liberal.” Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 12, no. 1 (1958): 53–58.

- Daniel Klein showed how, in English the word “liberal” underwent a dual transformation in the second half of the 18th century: both quantitative, as the word began to appear more frequently after 1760; and qualitative, as it started to appear in compound forms (“liberal policy,” “liberal views,” and “liberal ideas.” It was associated with the idea of free action, free trade, and non-intervention. The change was not drastic, and as seen in Paine’s work, the term displays clear polysemy. For example, Dugald Stewart, in the 1790s, presented Adam Smith as a representative of the liberal system and as someone who thought of “freedom of trade” as distinct from “political freedom” (the latter, for him, being typical of the French Revolution). See Rothschild, 2003; Klein, 2014; and the text by Robertson in Clark, 2003

- Rothschild, Emma. Sentimentos econômicos: Adam Smith, Condorcet, e o iluminismo. (Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2003.)

- Crawford Brough Macpherson, A Teoria Política do Individualismo Possessivo: De Hobbes até Locke. (São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1979).

- Arendt, Hannah. Da Revolução. (Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília, 1988).

- Burke, Edmund. Reflexões sobre a Revolução na França. (São Paulo: Edipro, 2014), 36.

- Anne-Louise-Germaine de Staël, Des circonstances actuelles et autres essais politiques sous la Révolution. (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2009).

- Benjamin Constant, Principes de politique applicables à tous les gouvernements. (Paris: Hachette, 1997), 113.

- Macpherson, A Teoria Política do Individualismo Possessivo, 40.

- John Stuart Mill, Considerações Sobre o Governo Representativo. (Brasília: Editora da Universidade de Brasília, 1981).

- Michael Freedon, Liberalism: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). 84 Edmund Fawcett, Liberalism: The Life of an Idea. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

- James Traub, What Was Liberalism?: The Past, Present, and Promise of a Noble Idea. (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 18.

- Traub, What Was Liberalism,? 23.

- Modesto Florenzano, Começar o mundo de novo: Thomas Paine e outros estudos. (Tese livre-docência:Universidade de São Paulo, 1999), 10.

- Helena Rosenblatt, The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First Century. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 47.

- Daniel Gomes de Carvalho, O pensamento radical de Thomas Paine (1793-1797): artífice e obra da Revolução Francesa. Tese de doutorado, Universidade de São Paulo, 2017. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.8.2018.tde-12062018-135137. Acesso em 15 de fevereiro de 2020.