Daniel Gomes de Carvalho & Fernando Cyrrillo Jünior

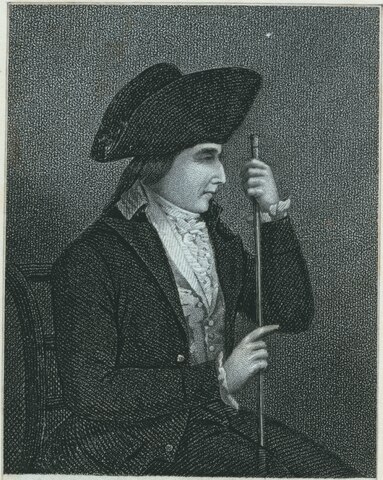

“In blasphemy and gross infidelity,” said the Centinel newspaper, Elihu Palmer “‘surpassed The Age of Reason by Thomas Paine and all other deist and atheist books.” Elihu Palmer (1764 1806) was a little-known freethinker who, even after losing his vision, remained active in the intellectual debates of his time. Palmer emerged as one of the leading exponents of deism in the First American Republic. Drawing upon thinkers such as Locke, Hume, Rousseau, and Jefferson, Palmer developed his philosophy by engaging with key currents of Enlightenment thought in North America, including Isaac Ledyard’s materialism, Thomas Paine’s deism, and John Stewart’s vitalism. For Palmer, true morality was rooted in an interconnected system encompassing all living matter. His ideas were widely disseminated through his principal work, published in 1801 and expanded in 1802, in which he proposed replacing religious dogma with ethics based on justice and benevolence.

Born in 1764 into a family of farmers in Connecticut, Palmer chose a public life after the end of the war in 1783, enrolling at Dartmouth College with the goal of pursuing the ministry or law. In 1787, he began his career as a preacher. At the First Presbyterian Church in Newtown, Long Island, an observer noted that he often set aside discussions of sin and instead urged his listeners to spend the day in innocent joys. Indeed, a year after beginning his ministry, he rejected Calvinist principles and became the “archetype of the radical and democratic deist.”

Soon after, he took a position at a Presbyterian church in Newtown, Long Island, where he met the physician Isaac Ledyard, who introduced him to the idea of eternal, living matter, questioning the existence of God as a transcendent entity. In 1792, he joined Philadelphia’s Society of Deist Natural Philosophers, which included Franklin and Jefferson, where he publicly denied the divinity of Jesus Christ, attracting the attention of clergy and generating tensions between religious traditionalism and new rationalist currents. When preaching to Baptists, he became frustrated with his audience’s reactions, as they expected nothing more than confirmations of their own doctrines. In the Federal Gazette, he wrote that opinions should not be subject to the whims of the masses—they should stand or fall solely by their coherence and truth.

TRAGEDY!

In August 1793, Palmer faced personal tragedy: a yellow fever outbreak on Water Street killed his wife, and he, treated by Dr. Benjamin Rush, was left blind. His enemies interpreted this misfortune as divine retribution for his heresies. Palmer then left his children to be raised by relatives in Connecticut and became an eloquent and tireless advocate of deism and vitalism. He became known for his sermons at the Deistical Society of New York and the Society of Theophilanthropists in Philadelphia.

In 1794, Palmer was profoundly influenced by Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason. He proclaimed Paine “one of the first and best writers of all time, and probably the most important man ever to exist on the face of the earth.” In Philadelphia, he resided in the home of radical poet Philip Freneau and became involved in the dissemination of the first deist newspaper in the Americas, The Temple of Reason, created and edited by Irish immigrant Denis Driscol. Between 1803 and 1805, he maintained his own weekly newspaper, Prospect; or, View of the Moral World. Due to his physical condition, Palmer wrote with the assistance of freethinker Mary Powel, whom he later married. Additionally, Palmer met John Stewart, who introduced the idea of sensitive atoms—particles that recorded sensations and composed the universe. This notion was incorporated into Palmer’s thought, reinforcing his vision of eternal and interconnected matter.

In 1801, he published his principal work, Principles of Nature; or, A Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery among the Human Species, in New York. The second and third editions, identical, were published in 1802 and 1806. Historian Kerry S. Walters, a professor at Gettysburg College and a leading scholar of deist thought, republished the third edition in 1990 with an introduction.

Like Paine in The Age of Reason, Palmer saw Creation as the true word of God, in contrast to revelations and miracles. Alongside this, he described a conception of creation that was heterodox even among deists: for him, a divine force engendered the world solely from matter. This supreme force, therefore, resided in matter itself—it was not necessarily sentient in the way humans conceived it, nor did it require worship. Nothing existed above or below matter—God’s laws were perfect, and believing in miracles would be an offense to the Creator. Recognizing this force, Palmer argued, would lead to a sense of universal benevolence embracing all things, inspiring the abolition of slavery, war, and all forms of oppression. Politics and religion were deeply intertwined—deism, for Palmer, was an eminently ethical-political force.

BLASPHEMY!

In the early 19th century, Palmer’s writings, like those of Paine, became targets of criticism. His political enemies used his ideas to create scandals, linking him to Jefferson in an effort to discredit the president. In March 1806, Palmer returned to Philadelphia for a final series of lectures but died on the 31st of that month at the age of 41 due to lung inflammation. His work, Principles of Nature, left an important legacy, promoting a philosophy based on reason, individual responsibility, and the pursuit of a morality that benefited society as a whole. Palmer believed that understanding the material condition shared by all things would foster an ethics of compassion, transforming human behavior and, consequently, the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aponte, Ryan Nicholas. Dharma of the Founders: Buddhism within the Philosophies of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Elihu Palmer. Georgetown Georgetown University, 2012.

Carvalho, Daniel Gomes de. O pensamento radical de Thomas Paine (1793-1797): artífice e obra da Revolução Francesa. 2017. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2017. doi:10.11606/T.8.2018.tde-12062018-135137.

Fischer, Kirsten. American Freethinker: Elihu Palmer and the Struggle for Religious Freedom in the New Nation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

Fischer, Kirsten. “Elihu Palmer’s Radical Religion in the Early Republic.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 73, no. 3, (Jul. 2016), pp. 501-530.

May, Henry F. The Enlightenment in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Minardi, Margot. “American Freethinker: Elihu Palmer and the Struggle for Religious Freedom in the New Nation” by Kirsten Fischer (Review).” Journal of the Early Republic 41, no. 4 (2021): 694–97. doi:10.1353/jer.2021.0095.

Walters, Kerry S. The American Deists: Voices of Reason and Dissent in the Early Republic. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1992. doi:10.1353/book.94120.