By the late George Hindmarch

We live in curious times amid astonishing contrasts, reason on the one hand, the most absurd fantasies on the other…… a civil war in every soul.

– Voltaire

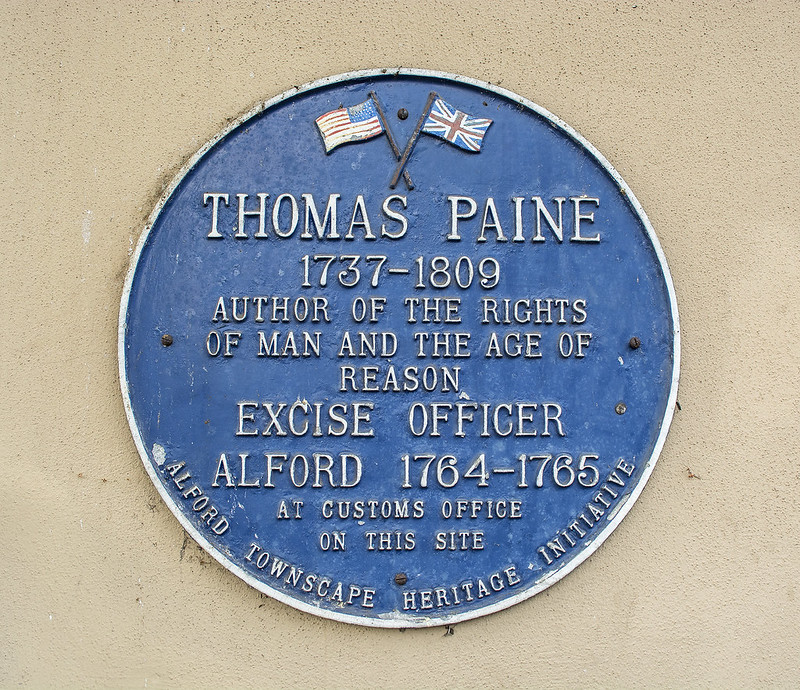

Paine’s dismissal from his excise appointment at Afford left him with a shattered career, and without immediate prospects. His regular income had slipped from his grasp, but despite his swift change of fortune and the suddenness of his dismissal, he was probably quite well placed to look after himself for a few weeks while he took stock of his position and sought a means to make a living. He could always return to his trade of stay-making if nothing else was available, but he had put that trade behind him when he entered the excise, and he seems never to have considered it serious again.

Oldys, the chief informant about Paine’s movements during his first English period, painted a very sorry picture of Paine after leaving Afford, but he probably did this to heighten the effect of Paine’s dismissal in the minds of readers of his life, and also to cover the inadequacy of his own knowledge of Paine’s next few months, and as usual when he was trying to convey a false impression, he carefully phrased his account to facilitate the drawing of adverse conclusions from unsubstantiated suggestions:

Our adventurer who appears to have had from nature, no desire of accumulating, or rather no care of the future, was now reduced to extreme wretchedness. He was absolutely without food, without raiment and without shelter. Bad, however, must that have been, who finds no friends in London. He met with persons who, from disinterested kindness, gave him clothes, money and lodging.

So strong has been the influence of Oldys over most later biographers of Paine, who appear not to have realised that the excise records were his chief source of information about Paine’s first thirty-seven years, that the picture he painted has usually been accepted without question. But it was no wretched ragged beggar who rode his own horse from Alford to London, for simple analysis of the known facts of Paine’s excise career to date indicates a very different situation.

Grantham, a busy town, would not have been the cheapest place in England for an excise supernumerary to maintain himself in the conservative style of living expected of a minor official and under the watchful eye of his Collector, but Paine livered there without known difficulty from December 1762 until leaving for Alford in August 1764. A supernumerary’s salary was only £25 a year, but on promotion to a ride officer in Alford, his salary would have doubled to £50, a considerable advance notwithstanding the attendant expense of acquiring and keeping a horse. His Alford duties entailed riding country roads that were frequently under water in winter, but which an exciseman nevertheless was required to negotiate, and he must have equipped himself with a serviceable wardrobe of stout clothing to enable him to continue riding in all weathers. And since Solomon Hansard (the landlord of the Windmill where Paine lodged) valued his excise connection sufficiently to retain it until he died, it is probable that Paine was able to lodge at the Windmill on very reasonable terms.

Paine applied for restoration to the excise within a year of leaving Alford, and it was by no means certain that his application would meet with success, for there were many instances of such applications being rejected by the excise board. When he did apply, his re-appraisal would have laid particular emphasis on whether he was free from debts, in accordance with standard excise practice; and this hurdle he was to surmount with consummate ease. It was in all probability as a thrifty young man with a supply of money saved during a year of quiet living that Paine returned to London, and there he would have been able to add to his reserves by selling the horse he no longer required. Nor would he have had any great worries about whether he would be able to find employment, for he himself was to detail the comparative ease with which a discharged excise officer could find a job when he came to write his Case of the Excise Officers a few years later.

The easy transition of a qualified Officer to the ‘Cornpting-House’ or at least to a School-Master, at any time, as it naturally supports and backs his Indifference about the Excise, so it takes off all Punishment from the Order whenever it happens.

Paine might have sought a teaching appointment in a country town such as Thetford or Afford, each of which maintained a notable school, but London seems always to have retained its magnetism for him. He had already lived there long enough to know the metropolis reasonably well and to appreciate that it offered the greatest scope for new employment; and it may have seemed the most attractive centre for his future studies. It was in London that John Wesley had his own church and this was sited not far from that other building to which Paine proposed soon to address himself — the Excise Office in Broad Street.

It is one of the stranger aspects of the story of Thomas Paine that the outstanding failure in his life — his personal religious struggle to promote a free community of men happily together in the light of the dispensations of a Supreme Being — has been largely lost to sight in the conventional accounts of his political struggles, which were but the means by which he strove to advance his mission. Not even the pioneer work of Moncure Conway, who first recognised religious motivation as the driving force in Paine’s life, has done much to dispel the general prejudice that Paine was primarily a secular revolutionary; yet Paine, the political innovator, was merely the working guise of Paine the idealistic preacher. John Wesley originated the Methodist practice of associating humanitarianism with assemblies of religious harmony; his follower, Thomas Paine, went much further and saw that religious harmony and social fulfilment were two equally important sides of a single golden coin representing the wealth of a happy contented people.

It was during the years after Alford and prior to his emigration that we can now see most clearly the original Paine, and can glimpse the pattern of his probable development had Fate dealt more kindly with him. Although already scarred, Paine then looked at life with compassion blended with quizzical humour, and would probably have made his mark as an influential and popular commentator on human affairs, pointing the way towards amelioration of the common lot. But that was not the path which would have led Paine to the great historic part he was to play in world affairs. In his later life, like John Bunyan and George Fox before him, he was to feel that Providence had taken a special interest in him and had intervened to influence his progress; indeed it may have been because he felt himself unable fully to comprehend the mysterious working of the Divinity in his own life that he did not publish an autobiography. And if there was one critical incident in which the Divinity covertly intervened to direct Paine’s path towards his destiny, it was surely in his diversion from the standard excise life and into intellectual originality. After leaving Afford and returning to London, Paine would have returned naturally to the circles in which he had moved before going to Dover, and it would have been his old Methodist friends whose ‘disinterested kindness’, to borrow Oldys’s words, helped Paine into his next profession of school teaching which was to become the springboard from which he made his great leap forward towards the spectacular achievements that lay ahead of him.

It was in July 1766, barely ten months after his dismissal from Alford, that Paine addressed himself to the Excise Commissioners. It is one of the unexplained inconsistencies in his story, which in most respects is poorly illustrated by personal documents, that Paine’s application to them has long been known in full. It was first published as early as 1817 by Richard Celine, an admirer of his political career who was persecuted and imprisoned for publishing Paine’s writings although he did not accept his religious opinions. Celine did not indicate how he learned the contents of Paine’s restoration application, but it is likely that the source was Paine himself. The application read:

London, July 3, 1766.

Honourable Sirs,

In humble obedience to your honours’ letter of discharge bearing date August 29, 1765, I delivered up my commission and since that time have given you no trouble. I confess the justice of your honours’ displeasure and humbly beg to add my thanks for the candour and lenity with which you at that unfortunate time indulged me. And though the nature of the report and my own confession cut off of expectations of enjoying your honours’ favour then, yet I humbly hope it has not finally excluded me therefrom, upon which hope I presume to entreat your honours’ to restore me. The time I enjoyed my former commission was short and unfortunate — an officer only a single year. No complaint of the least dishonesty or intemperance ever appeared against me; and, if I am so happy as to succeed in this, my humble petition, I will endeavour that my future conduct shall as much engage your honours’ approbation as my former has merited your displeasure.

I am, your honours’ most dutiful humble servant,

Thomas Paine.

The board’s minutes for the following day, July 4th record:

Thomas Paine, late Officer of Alford Outride Grantham Collection having petitioned to Board praying to be restored, begging Pardon for the Offence for which he was Discharged and promising diligence in future; Ordered that he be restored on a proper vacancy.

Paine’s history was given newspaper publicity in September 1871 when The Scotsman printed a letter from Mr. B. F. Dun, who had been for many years an officer in the excise. This letter first disclosed the Board’s misleading minute of Paine’s dismissal from Alford which Dun had seen on a visit to Somerset House [where the records were stored], and this fresh item about Paine attracted journalistic comment from G. J. Holyoake, who apparently received a further letter from Dun which the latter passed on to Moncure Conway. Dun seems merely to have disclosed the dismissal minute, expressed routine departmental opinions, and given a short conventional biographical sketch of Paine which included his previously-known restoration application in full as a natural sequel to the dismissal minute. But Dun’s connection with the excise induced Conway to overate him as an informant, with the result that instead of subjecting Dun’s account to critical scrutiny, Conway welcomed it at face value as supplying additional authentic information beyond that already publicised by Oldys.

There are several points arising from Paine’s restoration petition which call for consideration when reconstructing his position at this time. The first is the address at the top of his letter, the single word London. No experienced person in any age addresses to a government office an appeal which he hopes will elicit a favourable reply, without making arrangements to be informed of the response. There is but one logical conclusion to be drawn from Paine’s use of this single word address, he addressed his letter from the London Excise Office itself during personal attendance there, and arranged to call again as necessary to be informed of any progress.

It would have been quite inconsistent with the detailed vetting Paine had to undergo on first applying for an excise appointment, if there had been no formal re-appraisal before re-appointment after an alleged offence incurring dismissal, with its consequent heavy blot on his official character. Perusal of the exercise archives reveals a number of instances of applicants for restoration failing to pass this second vetting, and where reasons for rejection are recorded, inquiries into personal solvency figure prominently. Yet Paine’s formal application dated July 3 was approved by the Board on the following day; the circumstances indicated by this apparently swift processing of his application are not difficult to envisage when the ways of the excise are taken into account.

Instead of conducting his restoration application by letters submitted through the post, Paine initiated his attempt by a personal call at the central office, where he would have been interviewed by the official responsible for such matters, who at the time was a Mr. Earle. Paine’s record would have been examined, and any necessary enquiries conducted by Earle, who would have invited a formal application from Paine on their satisfactory conclusion, which Paine therein made out on the spot In accordance with standard excise routine his letter would have been headed by the name of the office of origin; thus the single word London was all that was necessary.

The tone of Paine’s petition has surprised some commentators, who have thought it servile; but his repeated expressions of humility has occasioned no raised eyebrows amongst excisemen, in the experience of the present writer. For Paine’s letter is a perfect example of the style Commissioners are believed to consider fitting in addresses to their august selves. It is highly probable that the petition was phrased on the advice, and possibly dictation, of Earl. Paine’s own character shows only where he claims he was never accused of dishonesty or intemperance, and thereby excludes any admission of having stamped a survey [having stamped an interest as having been taxed but not having actually been so].

Earl would have re-examined the circumstances of Paine’s dismissal scarcely two months after processing Swallow’s [William Swallow, Paine’s supervisor) appointment as supervisor at Caister following restoration, and in 1766 he was probably better informed than Paine himself about the outcome of the affair at Alford. As a responsible headquarters official with experience in personnel and disciplinary matters, had been aware of Swallow’s admitted misconduct at Afford [Swallow was later himself dismissed having admitted faking the charges against Paine]. It is to be observed that the board’s minute restoring Paine speaks of his begging pardon for his offence, although he had not done so; it is likely that Earle under-wrote his petition by a reports based on a personal interview which gave this impression, and that he did so to obviate any possible reluctance on the part of the commissioners to refuse the application. That Paine’s petition struck the right note with the board is demonstrated by the remarkable swiftness of its acceptance, and the fact that it took place only a day after Paine submitted it is a further strong indication that he penned it in the excise office and did not submit it through the post. John Tucker, another discharged officer, whose application for restoration was considered at the same time as Paine’s, does not appear to have been as well advised about the appropriate style of petitions as Paine had been, and he did not conform to the requisite ritual grovelling; the minute recording Tucker’s failure immediately follows that detailing Paine’s success.

Restoration did not confer swift re-appointment to an excise station, and Paine would surely have had his name added to a waiting list there was nothing he could do now except to wait patiently for a summons to return to the service, but in order to ensure that the summons when it was eventually issued should reach him, it was necessary for him to register his private address with the board and keep the central office informed of any subsequent change in personal circumstances during the waiting period. Paine therefore would have reported his post-restoration addresses and movements for inclusion in his personal file; there Oldys found them in due course when he was given access to that file, and he abstracted for publication such details as suited his purpose.

Oldys cognisance of Paine’s excise records explains very simply his remarkable proficiency as the first biographer of Paine, and his ability to disclose details which other biographers have not been able to verify should have pointed to the air source of his information. However, as Paine had no reason to declare his movements between his first dismissal and his restoration, Oldys was not informed of this period from excise sources, and it was probably to cover his ignorance about those months that he depicted Paine as having been penniless and homeless at that time.

There is an interesting error of fact in the Oldys account of Paine’s restoration. Whereas the board’s minute books establish absolutely that Paine was restored on July 4, Oldys dates that event as July 11, although the manner of writing the figure 4 in the minute book precludes any confusion with 11. The working system in the personnel section is detailed in the excise archives. It was the task of the clerks to translate the board’s decisions into appropriate instructions and letters, and this could only be done after the minutes of the day had been written up and passed to them. The restoration minute bears the appropriate tick, the initials of the supervising official appear on the page, and these marks and the subsequent note ‘he has had notice’ are indications of subsequent action which would not have been completed for a few days, and would have appeared in Paine’s file where Oldys would have found it recorded. In that file the completion of action was probably dated July 11, and Oldys mistook this date for the restoration date itself.

The further details Paine registered with the board after his restoration had been approved, enabled Oldys to reveal significant facts about the ensuing period, which was a very important one in Paine’s life; for it was now that he was able to extend his education and prepare himself for his great intellectual advances. Oldys informs us that he began to teach at the great academy kept by Mr. Noble in Goodman’s Fields, earning a salary of twenty pounds a year, with an allowance of another five pounds for finding his own lodgings in nearby WhItechapel at the house of a hairdresser named Oliver.

Daniel Noble, Paine’s new mentor, was one of a group of Baptist ministers who included Arminian views in their philosophy, and he would this have been amicably disposed towards Wesleyan Arminians, from whom may have come the recommendation that led to him employing Paine as an assistant However, it may have been that Paine had taught in other places during the ten months when his movements remain unknown to us, and that he worked his way up to Noble’s establishment through experience of teaching in lesser schools.

The dissenting academies owed their origin to the Act of Conformity of 1662 which had forbidden dissenting ministers to teach in established colleges and had driven them to found their own centres of learning. Their original attitudes of mind had guided their academies to a much higher standard of instruction than was to be found in the long established grammar schools such as the one Paine had himself attended at Thetford. The main impetus was not conditional on proficiency in the latin language, but was placed upon developments in the scientific world; in consequence, some of the clearest-sighted and most influential men of the country were glad to send their sons to these academies, which accepted adherents of all faiths, and were rated by many progressive minds as superior to universities.

In this fresh environment, and at the comparatively late age of twenty-nine, Paine at last had access to the new learning of his day, and was able to join whole-heartedly in the study and evaluation of advances in scientific knowledge. Astronomy figured high in his interests, and he himself recorded that as soon as he was able he had purchased a pair of globes and attended philosophical lectures, where he would have made the acquaintance of some of the most notable astronomers of his day, and perhaps established contact with other pupils of note. His close associated of later days, Thomas Rickman, was himself to record:

I remember when once speaking of the improvement he gained in the above capacities and some other lowly situations he had once been in, he made the observation: °Here I derived considerable Information; indeed I have seldom passed five minutes of my life, however circumstanced, in which I did not acquire some knowledge’.

Education is most swiftly accomplished in the early years of life. As spring is the season when nature reproduces last year’s foliage in quick green growth, so is youth the time when the knowledge’ our forefathers slowly gathered is most easily re-created by progressive study under the guidance of teachers. But even brilliant young students may not develop Into skilful practitioners until student days are left behind and they approach their work from practical angles. There are differences which can produce varying attitudes to problems from relatively unquestioning students and objectively viewing operatives, and these are perhaps never more impeding than when a practical man becomes a scholar. Difficulties that may not occur to an academic student may then arise out of his remembered experience to hinder smooth acceptance of progressive tuition. Because his practical mind already reaches out from intermediate stages, he is less likely to be able to accept scholastic opinions as secure platforms by which to advance towards his goal.

Paine not only had a mind thirsty for knowledge, but he possessed also a varied background against which to set his new ideas. In the ten years that had elapsed since he left his parental home, his restive spirit had led him into many situations. He had worked in town and country, at sea and on land; he had been apprentice and master-tradesman, religious convert and preacher, he had been stay-maker, privateersman, class-leader, exciseman and now schoolmaster, and he may have followed other professions as well since Rickman referred to ‘some other lowly situations he had been in’ without specifying them.

A man who comes late to the fount of contemporary knowledge has to struggle harder than his youthful contemporaries if he is to benefit fully from his opportunity; but if such a man succeeds, he acquires erudition more widely and more soundly based than theirs, for in the process he will have worked out within his own mind and from his own initiative many more problems than they; and in overcoming these additional difficulties he develops an indigenous momentum of thought which carries him forward more swiftly than his fellows. This enables him to appreciate the wider implications of new concepts, to relate them to the every-day world he already knows and understands, and to realise how they will be viewed by the ordinary people who inhabit it.

As his comment to Rickman makes clear, Paine used his return to the scholastic sphere to expand his existing knowledge; he would also have been able to fill in some of the gaps in his original schooling that had resulted from the restricting tenets of his Quaker father, and to re-examine questions that had troubled him, such as the concept of redemption which had perplexed his childish mind. He would not have been concerned to construct a basic philosophy as a young student might have been, but rather to test and advance the views he had already worked out during his chequered career to date. In a dissenting academy headed by a minister, Paine would have had opportunities not only to acquaint himself with the progress of science, but also to study the early history of Christianity. The new ideas he encountered did not disturb his basic belief in God, but they seem to have stimulated re-appraisal of the attitudes of the Anglican Church. Paine’s analytical mind began to identify pagan traditions that had been grafted onto the original teaching of Jesus by church-makers; this had probably happened when pagan communities had been absorbed into the expanding early Christian church as their members had accepted the essence of the message of Jesus, but had retained their festivities and superstitions deriving from their interpretation of the annual waning and waxing of the sun, and of other important natural phenomena.

Paine reversed this process, and began to reject these additions, streamlining his personal religion into a simpler faith revolving around the ideas he found good in the philosophy of Christ This simplified Christianity did not conflict with the emergent scientific view of the universe, which Paine eagerly studied with the help of his newly acquired globes under the guidance of the astronomers whose lectures he was now able to attend. As a schoolmaster he now had facilities for after-school studies, whereas during his earlier period in London (as a journeyman staymaker) he had worked daily for from six in the morning till eight at night But as, and probably because, his own beliefs became strengthened through simplification, he found it difficult to countenance and excuse the indecision in lesser minds thrown into confusion by conflict between paganised Christianity and scientific concepts, and deplored the attitudes who became more confused they more they studied. A few years earlier, when Paine began to express in print his views as they had so far evolved, he developed the forceful style which was to become the hall mark of his major writings. From a careful sympathetic arrangement of his premises, he proceeded swiftly to his conclusions, and punched home his message in striking phrases that seized the imagination of his readers:

Among the various Kinds of Idolatry we have upon record, that of worshipping the heavenly bodies, seems of all others the most plausible and rational. Consider the Sun as an immense fountain of light and heat, ripening by his influence into lie and action all the several tithes of the animal, mineral, and vegetable kingdoms, and you may, I think, easily conceive how obvious and natural it was for the uninstructed heathen to mistake such a body for the God of this lower world. I remember at school being much pleased with Herodotus’s worshippers of the Moon, waiting to hail and welcome their rising Goddess with all the festivities of music, dancing &c., they were really Idolaters of taste. In all the grand machinery of the creation, I hardly know so fine an object as the rising full moon, especially in summer. After an oppressively hot day, which has thrown a languor upon both mind and body, can anything equal the coming of a grateful evening mild”, ushered in by such a glorious harbinger? What exquisite painting! What scenery! A very bulgy of nature, One of her richest repasts; Every sense seems regaled, every faculty harmonised and disposed to favour thought and reflection. And yet how lost, how utterly lost is all this to millions and millions? Why? Because we all look through different glasses; one has the lens of his (mind’s) eye so thick and horny that he sees no objects distinctly. Some view everything through the medium of gain; others through the misty glass of sensual pleasure. Some are blinded by ambition, others drunk and besotted by Intemperance. But of all, one is most vexed by these who are TOO SHARP-SIGHTED TO SEE, or, in other words, who have too much learning to have any taste at all, who are so bewildered in the labyrinth of science falsely so-called, that they are lost to everything worthy of their notice. Admirable work this!, to be learnedly stupid. A man in such a case is like a warrior pressed to death with the weight of his own armour.

The works of Herodotus, the Greek historian and traveller whose descriptions made a strong impression on Paine’s mind, were available in translation when Paine was ‘at school’ in the academies of Noble and Gardner; the importance attached to them is evidenced by the prefatory comment of the translator Isaac Littlebury that Herodotus first advanced history from fable and poetic fiction to ‘true dignity and lustre’. Paine probably used such translations and other kindred works to trace the residual forms of ancient practices in contemporary dogma. Philosophers of old had always been strongly influenced by the paramount importance of the sun in human affairs, and had progressed to a study of other celestial bodies, as the standing stones of Stonehenge and the massive sextant carved in the rock near Samakand bear witness, and, as the horoscopes widely printed in our own day confirm, such influences are slow to lose their grip. But Paine was an original thinker, and instead of becoming over awed by the immensities of the skies, his flexible mind found confirmation of divine purpose in the minutiae of Creation as well as its most significant manifestations:

One of the loudest Infidel batteries that have been ptay’d off against revealed religion, is that it abound in mysteries. It is absurd (they say) to require our faith in matters confessedly above the reach of our understanding”. The objection, at first sight, appears formidable enough, but it will be found, upon examination, to carry with it very little or no force at all. Whether a thing exists, and how it exists, are certainly two very different enquiries. Even among the objects of sense, which we may be supposed to be the best acquainted with, are every moment forced to acknowledge numberless truths, which, with the uttermost stretch of our faculties, we can no way fully conceive, nay, which we have hardly any competent idea of at all. The various modifications of matter, the exquisite mechanism, and organisation of animal and vegetable bodies, &c, are (as to their first rationale) utter secrets to us, and so they will ever remain. A single blade of grass is as effectual a puzzle-wit for all the philosophers on earth, as is Its Solar System, and twenty other Systems added to it.

The originality of mind Paine first displayed in his religious writing was later to find expression in his secular works also. Historians, like students of Nature, were drawn naturally to the influence of the Suns; and it was not by accident that Louis XIV of France became known as the Sun IGng, and that English history, even in the twentieth century, has been presented mainly in terms of the sovereign and his entourage. But modern commentators are coming to place less weight upon central authority and greater emphasis upon the effects by plebeian personalities. As long ago as the eighteenth century Thomas Paine had the vision to see the divine patterns in the minute as well as in the enormous, and he was one of the earliest to appreciate the potential goodness of the human spirit even in its modest manifestations in the minds of ordinary people. He realised that effective power could spring from such tiny units if peaceful persuasion could induce coalescence of a multitude of them in a common concerted purpose, and an understanding of how such persuasion could be exercised was to come to his mind over the following years. As Trevelyan has indicated, the beginnings of democracy as we know it are all traceable to the writings of Thomas Paine, and the power of this new force in domestic politics was to grow as his work was to become known to the general public through the mass distribution of cheap editions of his books, which Paine was always keen to promote.

RETURN TO THE EXCISE

Although the progression on Paine’s thinking may have been continuous, his career was destined to embrace a number of disjointed episodes, and in May 1767 he faced again the prospect of a change in his way of life when the opportunity arose for him to return to the Excise. In the Cornish town of Grampound, George Chappell the resident exciseman had been ill for some months, and when his supervisor reported that he was unlikely to be able to resume his duties, the Excise Board decided that he should be retired under the pension arrangements of the day. As no other exciseman had applied for the vacancy, the Commissioners turned for a successor to the waiting list, at the head of which now appeared the name of Thomas Paine, who was duly appointed. The Grampound post was a town division, otherwise known as a footwalk, which rated above an outride, so the posting was in the nature of a promotion for Paine as well as restoration to active service.

The term footwalk indicated an excise station where the work was sufficiently concentrated to be covered by foot instead of on horseback; but any impression of comparatively easy travelling which this seems to imply is misleading, for footwalks could be far from comfortable postings. The Commissioners had considered the ambulatory powers of their officers, and set the limits of footwalks as up to twelve miles overall for regular traders and up to sixteen for those visited occasionally, so town officers commonly walked up to twelve miles a day, with an extra four thrown in now and again for variety. It is not surprising that after being ill for several months Chappell was thought to be incapable of copying with the excise work in Grampound.

Lack of competition for the vacancy may have reflected the character of the town and its reputation amongst visitors. John Wesley preached there, and recorded an unfriendly reaction from the mayor, who asked him to move on. Such surly resentment of newcomers may have been a feature of local attitudes at the time, which an incoming exciseman might have had to face also. The operation of political bribery at parliamentary elections furnishes another illustration of the local atmosphere; one freeman of Grampound received more than one hundred pounds in cash during the six years preceding the election of 1754 to secure his vote. Local worthies accustomed to be treated with such exaggerated consideration could have been prickly customers of the exciseman, and throughout Cornwall these revenue officers had become accustomed to performing their duties with scant regard for the procedures decreed by the Board for the protection of the revenue. And Grampound, like Alford, was a one man excise station where the exciseman was thrown largely on to his own resources. Paine, as a restored officer, would have been particularly vulnerable to official repercussions if he was again represented as being at fault by his superiors or by influential local traders.

Paine may have had some idea of the peculiar excise conditions in Cornwall, which were so unusual that rumours about them must have circulated in the service; he may have consulted Earle and had been informed about them, or he could have made contact with London excisemen to keep himself familiar with service conditions in order to facilitate his eventual return to duty. Alternatively he may have been sufficiently wrapped up in his current activities to wish to continue them. Whatever his reasons, Paine decided against Grampound and requested to be allowed to await a further vacancy. His rejection of the proposed appointment was probably a wise one, as events were to demonstrate.

In the summer of the following year the Board ordered a general inspection of the Cornwall Collection which was organised in four districts under its collector, and was probably administered by between forty and fifty local officers. As a result of the consequent report, the collector and one supervisor were dismissed, the three remaining supervisors were reduced to officers and removed to other collections, two officers were dismissed, twenty-seven reprimanded and six admonished. The supervisor Truro, whose district included Grampound was dismissed; he was reported as having been remiss in Grampound in particular, where he rarely bothered to re-gauge important brewing vessels to ensure that beer duty was accurately charged, and the interchangeable letters in his stamp for marking hides, which should have been periodically changed as a safeguard against malpractice, had not been varied in thirteen years and had become rusted in their positions. The supervisor at Launceston was demoted to one of the town divisions at Lewes in Sussex, where he would have been able to recount the slaughter of the Cornish excisemen to his Lewes colleagues, amongst whom was numbered at that time Paine himself, who was probably thankful to have escaped being involved in the debacle.

As Paine sought restoration in the summer of 1766, only ten months after being dismissed, he must have seriously considered returning; but from movements he subsequently reported to the Board, Oldys was able to recount:

Paine’s desire of preaching now returned on him: but applying to his old master for a certificate of his qualifications to the bishop of London. Mr. Noble told him that since he was only an English scholar, he could not recommend him as a proper candidate for ordination in the church. Our adventurer, however, determined to persevere in his purpose, without regular orders. And he preached in Moorfields, and in various populous places in England, as he was urged by his necessities, or directed by his spirit.

A contemporary account of aspiring Methodist preachers at Moorfields is to be found in the memoirs of the publisher, James Lackington, who was at the time estranged from the Methodist movement to which he owed his start in business, and to which he later returned. Some latitude is therefore called for when considering his unfavourable comments, and his disparagement of itinerant Methodist preachers whom he depicted as frequently lodging at the houses of sympathetic widows, and readily abandoning their itinerancy if offered a permanent home by one of them. An essay by Paine entitled Forgetfulness, which he probably wrote many years later and which was preserved by being copied by a friend, also sheds some light on Paine’s movements at this time. In it he speaks of himself being ‘about the summer of 1766’ in a fenland village and lodging with a widow who was also sheltering a young lady in a depressed frame of mind following an unhappy love affair. Paine mentioned these circumstances because he was able to dissuade the young lady from an attempt at suicide, but in the present context they serve as an indication that Paine could already have been engaged in itinerant preaching about the time he applied for restoration in the Excise.

If Paine was already a circuit preacher in the summer of 1766, it means that he had been approved by the Methodist organisation. His practical experience and his repeated changes in his way of life would have indicated his adaptability, and hence his suitability for a nomadic life, and his experience of riding the difficult sunken roads of Eastern England as an exciseman would have made him a natural choice for East Anglican circuits. Paine possibly returned to Alford as an itinerant preacher about a year after he left it; he may have learned what had happened to Swallow after his own departure, and he may also have played a part in preparing the ground for the establishment of a Methodist group in the town, which was to come about within few more years.

At this critical stage in his life, it seems that Paine stood at a crossroads, with the separate paths of two different professions — the Excise and the Methodist ministry — diverging before him. But it would seem that he had not yet decided which path he would follow although he would soon have to make up his mind to which he proposed to devote the rest of his life. It is suggested here that the reason for his delaying his decision was his desire to pursue his evangelistic career as an ordained minister, a course which John Wesley encouraged his lay ministers to follow, and until he has ascertained his prospects for ordination Paine preferred to keep both his options open.

An attempt can now be made to reconstruct Paine’s position at this period, using as a basis the Oldys account, which would have drawn upon dated information given by Paine to the Excise Office:

Mr. Noble relinquished Paine, without much regret, to Mr. Gardner, and then taught a reputable school at Kensington; yet, owing to whatever cause, he here acted as usher only the first three months of 1767.

The adverse slant of Oldy’s writings cannot conceal Noble’s regret at Paine’s departure in early 1767, and it is also dear that Paine’s assistance was sought by a school of considerable standing, although nothing is further known about Mr. Gardner, its proprietor. Since Paine returned to Noble, a minister, when seeking a recommendation to the bishop of London in the spring of 1767 at the time of leaving Gardner, it is clear that Paine decided to test his prospects in the church about the time when he would have been preparing for another summer as an itinerant Methodist minister. In May 1767, when the excise station at Grampound was offered to him, Paine may have wished to hold himself readily available for ordination-studies, and it would have been for this reason that he decided against departing for distant Cornwall. And since the only known reason why Noble did not recommend him for ordination is his lack of classical education, Paine may well have concluded that the ministry was not closed to him, and that his chance of acceptance would be greatly enhanced if he added proficiency in the classics to his growing erudition.

The Oldys account leaves little room to doubt that Paine was again a circuit preacher in the summer of 1767. Great interest would attach to any reliable accounts of Paine’s preaching style, as they would indicate his approach to his listeners; even Oldys gives a hint in his remark that Paine preached ‘as directed by his spirit’, for Paine’s spirit was characterised by originality, and his sermons may have been arresting. But the scant references to his work in the field which have survived give no indication of his effectiveness beyond intimating that he was at last adequate in his addresses. However it is probable that Paine found a return to an itinerant life precluded continuation of the rapid advances in self-education that he had enjoyed during his periods as a schoolmaster in London. If acquisition of the classics, especially a knowledge of the latin language, had become one of his objectives, he may have found the prospect of another settled period in the Excise increasingly attractive because of the attendant improved facilities for systematic study.

Paine’s rejection of Grampound probably resulted in his name being returned to the bottom of the list of restored officers awaiting re-appointment, and it took nine months for his name to work its way back to the top. Then, at Abergavenny in Wales, Robert Henry Whitney, after having been seven times reprimanded and thrice admonished in the preceding three years, again incurred censure and was dismissed. The detailed account of the Board’s minute book of the multiple faults of this hardened offender once again highlights the harshness of Paine’s dismissal after an unestablished first offence at Afford. Daniel Jones of Wells Outride in Somerset obtained Abergavenny, and Paine was posted to Somerset, but following receipt of a letter from a certain Edward Dalton, the Board decided on different arrangements. Dalton, the officer at Lewes 4th Outride was now appointed to Abergavanny, Jones was ordered to remain at Wells, and Thomas Paine was appointed to the Lewes vacancy on February 29, 1768.

Thus a new chapter commenced in Paine’s life that was to have consequences which at the time neither he nor anyone else may have envisaged.