By Andrew Stevens, Director Of The Campaign For The Separation Of Church And State

It gives me the greatest pleasure to pen an article for the Bulletin of the society dedicated to honouring one of England’s finest radicals. Although not necessarily to be accredited with being the first to question religious privilege and accepted wisdom in spiritual affairs, Paine was undoubtedly their most fierce critic in his day and The Age of Reason articulates the disdain for and the contempt in which he held all-powerful religion, in both the constitutional and rational sense. I believe this was meant to complement his thinking on the subjects for which he normally receives more credit and recognition for today, namely popular rights and government. However, admirers of Paine often choose to revere these two concepts and ignore or give diminished consideration to his thinking on religion. It would be folly somewhat to imagine or argue that Paine’s radicalism and life trajectory followed some conscious logical progression and applied this to his output – Paine was not a scholar, nor did he enjoy the privileged upbringing of most seminal theorists of his day and nor did he hold any great public office. His works were, in the main, written to contend with contemporaneous events. However, it can be argued that in retrospect we can view Paine’s collective output as being consistent. He did not vacillate in his opinions during his life (unlike Locke for instance), the themes of each work corresponding with the others. Therefore, religious privilege can be viewed as deserving the same consideration as representative government and political liberty, the three having the same effect on man’s progress – this being as significant upon the politics of spirituality in the late eighteenth century as the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, and J.S.Mill’s On Liberty in 1859 was in the mid-nineteenth century. Whilst Mill and Darwin’s work ushered in an age of active nonconformism, anti-state church agitation and a belief that man’s progress and social reform lay in the hands of man himself and not the Christian church, Paine’s publication of The Age of Reason was met with the derision and fury of Christian both in Britain and America that would suggest that it was Paine himself that nailed Christ to the cross! To criticise the actions of men in their earthly affairs and dealings with one another was one thing but to challenge the accepted wisdom and belief of the Christian view of the world was above mere reproach.

Paine’s sane and rational perception of the unchallenged tenets of Christianity, as startling as their originality in his time remains, offers us little in an age where even the Papacy accepts evolution, over one-hundred years after Darwin and where the empirical work of scientists reduces the bible to a superstitious document of mythical events. However removed from the misconception of Paine being an atheist, his deism can be seen as perhaps an attempt for religion to circumvent the growing anti-clericalism and antipathy towards the church and was something of a precursor to Unitarianism. However, somewhat redolent of our own age perhaps, the prevailing view on Christianity and how the church should conduct itself was that articulated by the arrogant and sanctimonious forces of conservatism. We all know how Paine wrote Rights of Man as a spirited defence of the French revolution and the common liberty immediately after reading Burke’s, Reflections on the Revolution in France Thus it has been and remains so to some extent, that Burke and Paine are viewed as being the antithesis of one another – the advocate of the wisdom of the ages, reverence of the preceding order and of the stabilizing virtues of aristocracy, versus that of reason, the rationalism of man and society’s progress and revolutionary zeal. Indeed Burke in the Reflections wrote:

‘To them (the citizens), therefore, a religion connected with the state, and with their duty toward it, become even more necessary than in such societies where the people, by the terms of their subjection, are confined to private sentiments and the management of their own family concerns’.

Let there be no doubt or scope for misapprehension, Paine would disapprove of the established Church of England as much today as when he conceived an “age of reason” should prevail, perhaps more so given the length of time we in Britain have had at our leisure, and in much more tolerant times, to contemplate and resolve to liberate the Anglican faith from its stately captor. Whilst many a Tory could quote Burke verbatim and the publications offered for sale by Labour include Paine’s first two works, it is Burke’s view that prevails as rigidly and virtually unchallenged now as in 1789 as far as the established church is concerned. As asserted earlier, the pursuit of true representative government and the common liberty of all is bound to the belief in man and society’s progress alone, free from the dogmatic intrusion of either the superstition and myths of Christianity or the Burkian conservative and arbitrary national religion of the established church. However, to agitate for this is not to deny either Christians or their Protestant adherents the right to enjoy and practice their faith, it is merely to defend it whilst giving it parity with other denominations and faiths that they rightly deserve, altogether free of state involvement. The right to the free exercise of religion and worship, to to refrain from doing so altogether, is sine quo non in a representative democracy based upon the principle of liberty. As progressive democrats we possess the humility, something Christianity stresses so much, to allow others to advocate the curtailment of liberty, even though fundamentalist Christians would gladly snatch that very right alone from under our noses!

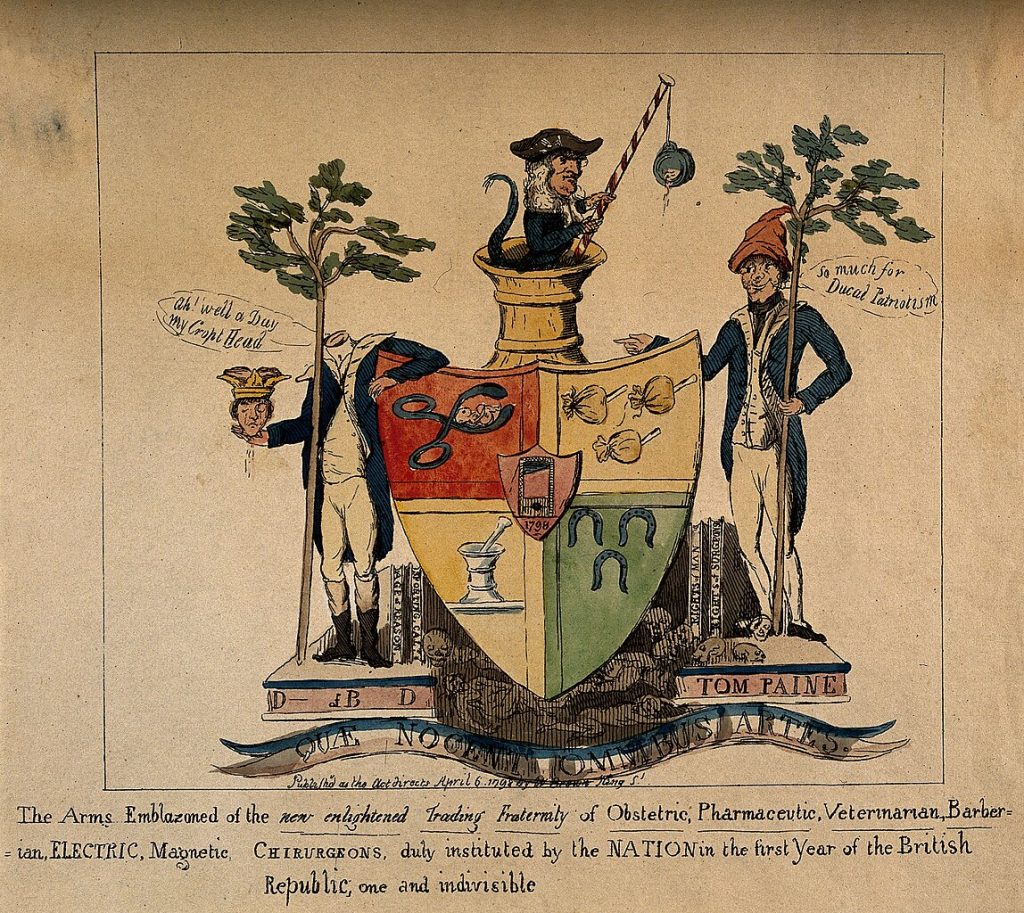

As the Thomas Paine Society we are dedicated to both constructing a perspective on the problems and issues we face in our own time and towards honouring Paine’s great work and memory. However, whilst Burke stressed the importance of ‘the three prejudices’ which today could be construed as monarchy, parliamentary government and established church, as opposed to Paine’s common sense, the rights of man and the age of reason, it is Burke’s view of which that our Labour Prime Minister believes in so strongly. Thus, whilst in our age Paine would not have effigies burned in his absence nor condemned to an undignified existence during the rest of his days for articulating such anti-established church sentiments; the chances are that they would fall upon the deaf ears of the unaware, unconcerned public (Burke’s ‘swinish multitude’) and a muted political reform movement that once sought to challenge vested interests and arrogant assumed wisdom with such unfaltering recidivist conviction. Whilst Paine is not with us today (unless you are a Buddhist perhaps), his words resonate so clearly and audibly that he might as well be: let every man follow, as he has a right to do, the religion and the worship he prefers’.