By Robert W. Morrell

Reading Dr. O’Brien’s article on The Age of Reason in the last issue of The Bulletin reminded me of the reaction of so many people when the essay first appeared. Although it contained ideas familiar to the world of scholarship these ideas had not in general filtered down to the average clergyman or most lay Christians, hence their horror at encountering such heretical ideas. Dr. O’Brien is, as his important study of Burke, Priestley and Paine, Debate Aborted (Pentland Press, 1996) illustrates, very familiar with Paine’s radical politics, which he supports, but he appears to have been shaken at encountering Paine’s theological ideas, describing some as “off-the-cuff comments” which are “intemperate and highly offensive to sincere Christians”. I cannot think of a single sentence in either part of The Age of Reason which can be so described. That Paine did not mince his words and spoke out clearly I would agree, but he deliberately sought not to give offence and unless Dr. O’Brien is contending that those Christians who do not feel as he does are insincere, then he has to grasp the stark fact that many who are as sincere in their opinions as he is in his differ fundamentally with him. As an example I cite the comments of the late Rev. Dr. J.M. Connell:

“As an argument for the existence and goodness of God, and a call to worship Him as He reveals Himself in the wonder and beauty of the universe, The Age of Reason is of first-rate importance in the literature of the subject. But it strikes us, at first sight, so strange and unpardonable that Paine should set aside the greatest religious book in the world as a thing of no account. For this treatment of the Bible, however, the responsibility lay rather with those who made exaggerated claims for the Bible, and sought to enforce them with all the authority at their command. The Bible was held by practically every religious denomination as the infallible Word of God, from its first page to its last. It was this claim that Thomas Paine set out to shatter, and he did so most effectively. Had the Bible been regarded, as to a large extent it is now, as containing elements human and divine, the errors of men as well as the truths of God, the likelihood is that The Age of Reason would never have been written. But Paine can hardly be blamed for not being more a man before his time than he was, and for treating the Bible from the then common point of view, and for showing that the claim that was made for it could not be justified at the bar of reason and conscience. He accomplished a rough but very necessary pioneer work… he certainly destroyed more stubborn fallacies, and the Bible is no worse for that, all the better indeed’ (Thomas Paine, A Pioneer of Democracy. Longmans Green & Co., 1939. pp.38-39).

Although he may not have realised it, Thomas Paine was a product of the Enlightenment, having through his friendship with many leading thinkers absorbed much of the advanced thinking it had produced and continued to. Many of these ideas ran directly counter to popular Christian ideas about their cult, as the theologian, Marcus J. Borg has noted, for “more than a millennium before the Enlightenment, the Gospels and the Bible as a whole had been understood as divine documents, whose truth was guaranteed by God. Therefore, it was taken for granted that the history they reported was guaranteed by God. Therefore, it also taken for granted that the history they reported had happened as recorded. It was simply assumed that Jesus as a historical figure was the sum total of everything said about him in early Christian tradition”. (Profiles in Scholarly Courage, Early Days of New Testament Criticism’. Bible Review] 0.5.1994. p.45).

There is no disputing that Paine challenged this belief, but he was far from being alone in this. When he presents Jesus as being no more than a man, or that the author of the Pentateuch was not Moses, he was saying no more than H.S. Reimarus (1694-1768) did in his book, On the Intention of Jesus and his Disciples, published posthumously for fear of it putting its author in danger. If Dr. O’Brien finds Paine’s theological ideas offensive. I dread to think what he would make of those of Reimarus.

Christian leaders have always feared criticism, and like the mullahs of present-day Islam, have systematically sought to suppress it. There is an echo of this in Dr. O’Brien’s observation that while Paine was “entitled…to have his own views” he had no right “to foist” them on the public in case he was thought by those who followed him as being “a potential expert” in theology. In fact Paine was a highly competent lay theologian being far better informed than most of his critics, while those on par with him such as Priestley and Watson, are noteworthy for accepting much of what he wrote, though often with obvious reluctance. Thus Priestley concedes Paine’s argument on revelation, but sought to reduce its significance by claiming, “we do not say that revelation made immediately to Moses, or to Christ, is strictly speaking, to us (Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever. Part 3, Containing An Answer to Mr. Paine’s Age of Reason. Philadelphia, T. Dodson, 1795. p.27). In addition, he also, like Paine, refers to prophets as poets (p.77). .

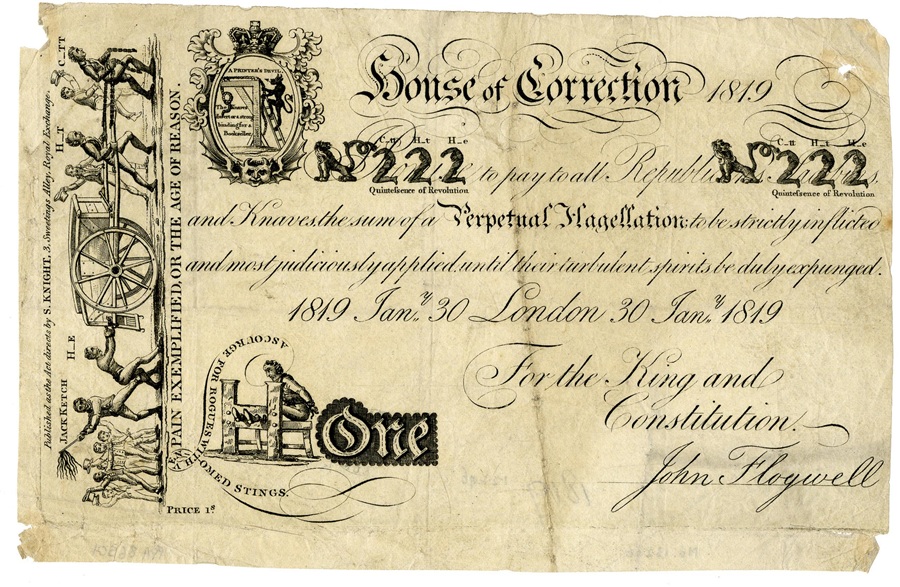

When Christianity was imposed upon the Roman Empire its bishops sought to eliminate all works critical of their cult, its beliefs, practices and claims, thus in 326 CE they had the emperor Constantine promulgate an imperial edict ordering all books written by “heretics” (eg. those by Christian holding minority opinions) be hunted down and destroyed. In 333 CE this was extended to encompass all pagan works critical of Christianity, these were “to be consigned to the fire”. The dominant European Christian sect, Roman Catholicism pursued any potential challenger of its ideas. We see this in a book by a learned judge, Nicholas Remy (1530-1612). In it he writes of himself and his fellow judges sentencing very young children to be “stripped and beaten with rods around the place where their parents were being burned alive” because they were tainted with their parents heresies. He writes at length of one Lawrence of Ars-sur-Moselle who had participated in a coven at which he had turned the spit on which meat had been roasted. The learned judges (Remy was Attorney-General of Lorraine) debated his crime at great length, and while some wanted to send the prisoner to be burned alive at the stake, humanity prevailed and it was decided to sentence him to perpetual imprisonment in a convent run by the Minims, who, Remy explains, were “exceedingly strict” and who practised “extraordinary self abnegation” and cultivated “a spirit of humblest penitence” (Demonolatry. Edited by M. Summers. John Rodker, 1930. pp.95-98). This fate must have been a long drawn out hell on earth for the victim, who, before I forget it, was only six years old. In a period of ten years Remy sent 900 men, women and children to be burned alive as witches, naming 128 in his book, which was first published in 1595 and frequently reprinted and used by other inquisitors and judges as an authoritative source. To avoid appearing to be biased by singling out Roman Catholicism, I cite an example of Protestant brutality, that involving Thomas Aikenhead. This 18 year old youth was hanged in Edinburgh in 1697 for the heinous crime of maintaining that Ezra not Moses was the author of the first five books of the bible, holding that Jesus was not god, rejecting the trinity and being a deist. All these ideas can be found in The Age of Reason, and the successors of the Edinburgh clerics would have gladly hanged Paine, while Remy would have delighted in burning him for he considered unbelief to be equal, if not worse, than witchcraft, but bemoaned the difficulty of discovering such people as they kept their opinions to themselves (p.vi).

One important fact has to be grasped, one which Dr.O’Brien pointedly ignores, namely that Paine’s criticism of Christianity was as much political as it was theological, as the historian, E.J. Hobsbawm so succinctly put it, throughout pages of The Age of Reason:

“there glows the exaltation of the discovery of how easy (his emphasis) it is, once you have decided to see clearly, to discover that what the priests say about the bible, or the rich, about society, is wrong” (Labouring Men, Studies in the History of Labour. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968. p.4).

Nowhere in his book does Paine deny the historicity of Jesus, Mary or Joseph, although he would have been familiar with the mythicist thesis of his colleagues Volney and Dupuis, but he rightly questioned the validity of some of the claims made about them. He does not, as Dr. O’Brien claims, hold that gospels were “all written in or about the same time by individuals who had lived with Jesus….”, but says we do not know who wrote them. As to when they first appeared, Paine writes of this being “a matter of uncertainty”. Perhaps Dr. O’Brien should have read The Age of Reason with less indignation and more care, for had he done so he would have discovered exactly what Paine thought of Jesus. He would have encountered his emphasis on Jesus’s Jewishness, and his argument that it was others who put a veneer of supernaturalism on him. Jesus, Paine maintains, was a man not a god and had no intention of starting a new religion. Here, too, it is worth noting that in Judaism, as the distinguished Jewish scholar, Hyam Maccoby has pointed out, for anyone “to claim to be the Messiah was simply to claim the throne of Israel”, an office carrying “no connotation of deity or divinity”. Nor was it blasphemous to make such a claim, as it was open to anyone to put himself forward as messiah (H. Maccoby. The Myth Maker, Paul and the Invention of Christianity. 1986. p.37). Paine appears to have been fully aware of this and so I would suggest that contrary to what Dr. O’Brien claims he possessed a very profound and deep understanding of Judaism, which is why he saw Jesus as a political agitator who wanted to free his fellow citizens from foreign domination. He makes this point vividly in the quotation from The Age of Reason which I reproduce below and with which I conclude:

“The accusation which those priests brought against him was that of sedition and conspiracy against the Roman government, to which the Jews were then subject and tributary; and it is not improbable that the Roman might have some secret apprehensions of the effects of his doctrine, as well as the Jewish priests; neither was it improbable that Jesus Christ had in contemplation the delivery of the Jewish nation from the bondage of the Romans. Between the two. however, this virtuous reformer and revolutionist lost his life” (my emphasis – RWM). (P.S. Foner, The Life and Major Writings of Thomas Paine. 1974. p.469. All other quotes from Paine come from the same work)