By Eric Paine

Of Moses the great lawgiver of Israel we read that, “no one knoweth of his sepulchre”. The same may be said of Thomas Paine, who was a mighty potent force in advancing a better system of government, human rights and much else in America, Britain and France. It took time for his message to be heard but the history of the spread of democracy cannot be written without it.Yet why do the people of Britain generally know more about Pepys of the 17th century than Paine of the 18th. century?

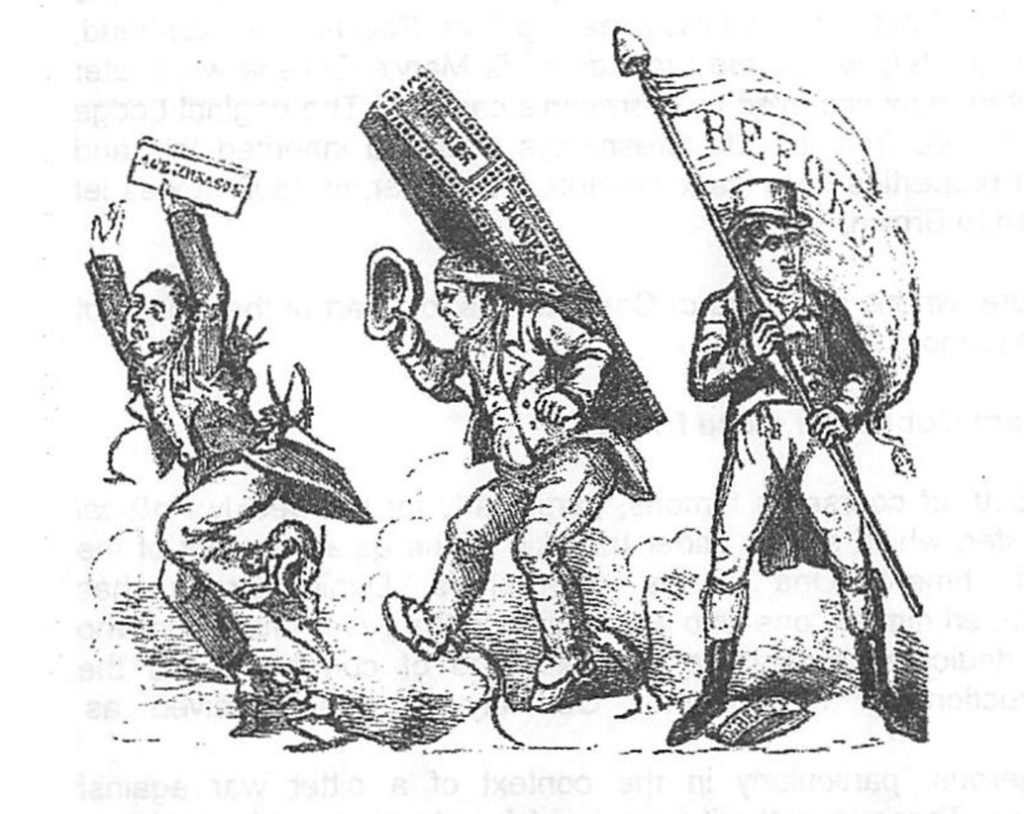

It was William Cobbett who dug up Paine’s bones in the dead of night in 1819 and brought them back to England with the intention of building a mausoleum in his honour. Appropriately the ship carrying his remains was the ‘Hercules’. Earlier Cobbett had written misguidedly in the USA, “How Tom gets a living or what brothel he inhabits I know not. He has done all the mischief known to man in the world and whether his carcass is the last to be suffered to rot in the earth or to be dried in the air is of little consequence”. Yet after Paine died he changed his opinion, writing in his Register, “We will honour this noble of nature, his memory, his remains, in all sorts of ways. The tomb of this noble of nature will be an object of pilgrimage with all people”. But what actually happened?

Upon opening the coffin at the Liverpool Customs House, Cobbett said, “These, gentlemen, are the mortal remains of Thomas Paine’. True to form the plate on the coffin bore the wrong date of death, seventy-four instead of seventy two years. The coffin went to Cobbett’s London home and two years after his death to his farm near Farnham, Surrey. Soon after their arrival a Bolton town crier was imprisoned for announcing this. The Times and The Courier attacked Cobbett for bringing Paine’s remains back with great vindictiveness. Former friends shrugged their shoulders and Members of Parliament ridiculed him, so he rather furtively kept them until his death, making it rather late as an MP.

A few years before death Cobbett became permanently estranged from his family and a Mr. Tilley became his secretary and constant companion. After Cobbett’s death his son engraved Paine’s name on his skull and other bones, but when his effects were sent for auction the auctioneer refused to put Paine’s remains up for auction. The Lord Chancellor’s was appealed to but declined to consider them as part of Cobbett’s estate and refused to make any order concerning them. The box was taken by a Mr. West, one of Cobbett’s trustees, but when he subsequently failed as a farmer he sent them to Mr. Tilley, who in 1847 was living in Stepney.

In 1818, a Stepney Baptist minister named Reynolds said he had purchased for £25 some manuscripts and other items of Cobbett’s via a family named Guin, among these being Paine’s brain, or part of it, that had been removed from the skull by Tilley. He also said that following Tilley’s death a bag containing Paine’s bones had been thrown out.

Moncure Conway in an article he contributed to the New York Sun in 1892, said that he had purchased a small portion of Paine’s brain for £5, which he buried below the Paine monument at New Rochelle in 1839. There are also reports of Paine’s jaw having been buried in Wales and his bones having been buried at Ash near Farnham.

Now who should we blame for this dastardly treatment of the remains of one of mankind’s greatest benefactors? First in line of censure must be the New Rochelle Quakers for refusing Paine burial in their graveyard. This would have been most appropriate in view of the strong Quaker beliefs of his father, which he had instilled into his son.

The Lord Chancellor of Britain must also be held culpable for not ordering a proper burial, but most of the blame rests with that great agitator and enigma, William Cobbett, and perhaps later with his son. If financial problems were the main difficulty in Cobbett’s failure to provide his planned mausoleum, then he could have appealed for financial assistance from his Liberal minded friends, or did he fail to do this because he feared it would effect his chance of election to the House of Commons?

In the circumstances it would have been better, perhaps, for Cobbett to have left Paine’s remains at New Rochelle, where he had been buried with only five people present, two being Negroes who stood as witnesses to his efforts to end slavery, the others being Mrs. Bonneville, long time platonic friend of Paine’s from France, her son, and a Quaker, Willett Hicks. Had his remains been left they would have lain for ever in the land granted him by New York State in gratitude for his services to American independence.

However, Cobbett unwittingly did the right thing for the wrong reason, for the first real Citizen of the World belongs to no one country. Paine’s memory is part of the cultural history of all peoples and we should be proud of that fact.

Editor’s note: This unpublished article by the late Eric Paine appears to have been prepared initially as a lecture given to the William Cobbett Society on April 25, 1992