By Jeremy Goring

Most biographers of Thomas Paine say something about his early religious associations. There is general agreement that his father was a Quaker and his mother an Anglican, that he was baptised and confirmed into the Church of England and that as a boy in Thetford he preferred the quiet meetings of the Friends to the services at the parish church. It is also well known that, although he continued all his life to admire the Quakers for their good works, he could never completely accommodate himself to their life-style.

Though I reverence their philanthropy I cannot help smiling at the conceit that, if the taste of a Quaker had been consulted at the creation, what a silent and discoloured creation it would have been! Not a flower would have bloomed its gayeties nor a bird been permitted to sing.

But if neither the Church nor the Quakers attracted him, where could he find a place to belong religiously?1

John Keane, in a biography that has been acclaimed as ‘definitive’, has suggested that as a young man Paine had a significant ‘brush with Methodism’:

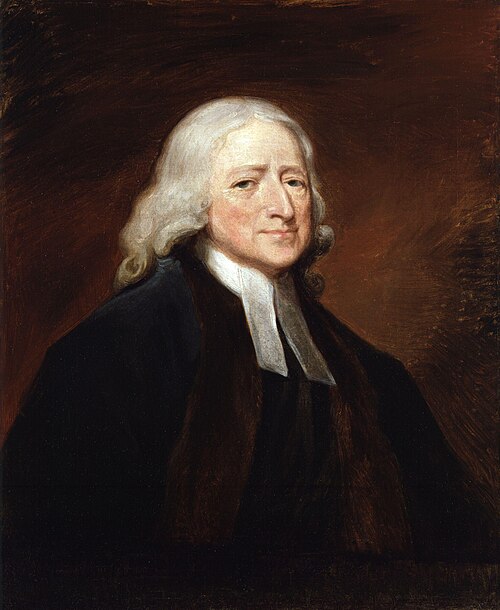

In Thetford Paine reportedly heard John Wesley preach. Wesley’s journal also records that when Paine was living in Dover, Benjamin Grace, Paine’s employer, took him along to the Methodist chapel on Limekiln Street, where Paine, aged twenty-one, confessed himself a believer and later preached sermons to the congregations (‘the hearers’) who gathered in that chapel.

This gives the impression that Wesley, who frequently visited Dover, had himself supplied this important information. Only those readers who turn to Keane’s copious endnotes will realise that the Dover story did not come from Wesley but from the editor of the 1916 edition of his Journal, who recorded it in a footnote. The authority he cited was an article that had appeared ten years previously in the Methodist Recorder, in which an anonymous contributor — following a day trip to Dover — assembled a few miscellaneous facts about the local history of Methodism. After describing the chapel that Wesley had opened in Limekiln Street the writer added this interesting snippet:

The building in question, now a public house, has one queer association. Tom Paine, author of The Age of Reason, read a sermon there one day. He was apprenticed to Mr.Grace and went with him to class and chapel. He professed to believe, and was so far trusted that when a minister failed one day Tom Paine took the service.

Since the information was provided by a leading Methodist whose family had lived in Dover for generations there is likely to be some truth in it. In fact, as Keane points out, the story is attested by this inscription in a copy of Wesley’s Sermons on Several Occasions taken to America in the nineteenth century:

Out of this volume Thomas Paine, author of The Age of Reason, used to read sermons to the Congregations at the Methodist Chapel in Dover when they were disappointed of a Preacher. At that time he belonged to the Methodist Society in that place.

Be that as it may, Paine did not stay long in Dover. After only a year he moved to Sandwich where he remained until 1761 and, according to a local tradition, sometimes preached ‘as an independent or a Methodist’ to small gathering in his own Iodgings.2

Paine’s involvement with Methodism, it is suggested, did not end on his departure from Sandwich, as Keane speculates that during the year and a half he spent as an Excise officer in Grantham (1763-4) he relieved his boredom either by ‘socialising with patrons of the George inn’ or by ‘mixing with local Methodists’ — activities that, in view of the Wesleyans aversion to alehouses, might be considered barely compatible. The mixing with Methodists is said to have continued after Paine, following brief sojourns in Alford and Diss, eventually moved to London in 1766. Here for a time he eked out a living by teaching in an academy run by Daniel Noble, which, according to Keane, ‘stood in a forest of private-enterprise schools then shooting up in London.

Some of these charitable schools were run by Methodists and Methodist sympathisers for labourers’ children, who were taught godliness, craft skills, and their social duties and rights. Noble’s academy was one of these.

It is, however, rather misleading to include this academy in the general run of ‘charitable schools’. Noble was no ordinary private school proprietor and was almost certainly not a ‘Methodist sympathiser’. Such a description is not borne out by the brief biographical details Keane himself supplies.

[Noble] had been well educated at the Kendal Academy under Caleb Rotheram (a friend of Joseph Priestly) and at Glasgow University. He had a large private library and was well known for his Dissenting sympathies and active support for civil liberties.

Apart from the confusion of Rotheram with his son of the same name (who was Priestley’s contemporary) his description of Noble, taken from a letter written to the Times Literary Supplement by the Baptist historian Ernest Payne, is accurate and to the point.3

Keane considers it likely that Paine assisted Noble in the work of preaching to his Seventh Day Baptist congregation at Mill Yard. He also gives some credence to a tradition that during his brief residence in London he preached in the city’s open fields. Here again, it is suggested, there was a significant link with Methodism.

The Methodists, for whom he had preached in Dover and Sandwich, welcomed lay preachers in the struggle for ministers especially among London’s poorer folk, whose souls they thought could be saved from wickedness and whose lives could be defended in the name of humanity and civilization.

But would they have welcomed Paine as a preacher if they had known that he was an associate of Noble? As Ernest Payne pointed out, Noble ‘belonged to a group of Baptists who added Arian sympathies to their Arminian and Sabbath-Keeping views’. . Moreover, as another Baptist historian W. T. Whitley expressed it, ‘he did not escape the drift towards Socinianism• which was prevalent nor did he seem to have been attracted by the revival under the early Methodists.4

Paine in Lewes

As it transpired, Paine’s association with Noble was not to last long. Early in 1768, having been appointed to the post of Excise officer there, he left London and moved to the Sussex town of Lewes, where he took lodgings in the house of a tobacconist named Samuel alive. Keane states that he acquired this accommodation ‘through Methodist connections’, but, since there were no Wesleyans in or around Lewes at this time, this is highly unlikely. It was not until the nineteenth century that Lewes became what he calls ‘a town of Nonconformist churches’. Apart from the Quakers there were in Paine’s day, only two non-Anglican congregations there and both belonged to ‘Rational’, as opposed to ‘Evangelical’, Dissent. These were the General Baptists in Eastport Lane, and the mixed Presbyterian-Independent congregation at the Westgate Meeting, to which Ollive — who lived next door at Bull House — himself belonged. By this date the General Baptists and the Presbyterians, who were eventually to unite to form a single Unitarian congregation, were drawing closer together. Therefore it may be that, metaphorically speaking, Paine came to Bull House by way of Eastport Lane. The little congregation meeting there formed part of a General Baptist association extending throughout Kent and Sussex with which Noble, who was later to be invited to become their ‘Messenger’ or district minister, was closely associated. When needing help to find lodgings in Lewes it would have been only natural for Paine to turn to him.5

Where did Paine worship during his six years in Lewes? Lodging where he did, it is likely that, if he went anywhere, it would be to the Westgate Meeting. ‘Bull Meeting’, as it was also sometimes known, and Bull House had originally been one building and the wall of partition between them remained thin. Indeed, if Paine stayed in bed on a Sunday morning he might have heard the singing of psalms next door. On occasion he might have been inclined, if only out of courtesy, to accompany the 011ives to their family chapel. It is said that it was here that he went with Samuel’s daughter Elizabeth in March 1771 to exchange vows before going to be legally married to her at St. Michael’s church over the road. It is likely, however, that he was never formally a member of the Westgate congregation. The shilling a year that he agreed to pay to the trustees was not a membership subscription. It was, as he expressed in a letter to them in 1772, ‘an acknowledgement for their sufferings the droppings of rain’ which fell into the meeting- house yard from a structure that he had erected above it.6

Had he attended services at Westgate Paine would probably have approved of the preaching of Ebenezer Johnston, the liberal- minded Scotsman who had ministered there since 1742. Like Noble he had been educated at a Dissenting academy and well grounded in the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Although none of his sermons survive it is certain that, like all the Rational Dissenters, his emphasis would not have been upon the saving work of Christ but upon ‘practical religion’. At a time when many Protestant Dissenting congregations were experiencing divisions and schisms, Johnston succeeded — possibly by being ‘all things to all men’ — in keeping his people together. Although probably not himself a Socinian, he would have tolerated heretical views if he encountered them. And so if Paine, in the course of conversation, had expressed doubts about the Atonement or the Trinity or even gone so far as to question the whole idea of revealed religion, Johnston would not have been shocked.7

It is not certain where Paine stood theologically during his time in Lewes, but it is clear that he was mentally on the move. For many people their early 30s are formative years and for Paine, who was regularly exercising his critical faculties and speaking skills in debates at the local Headstrong Club, they may have been specially so. If, as Keane suggests, he was the ‘P….’ who wrote a satirical poem entitled ‘An Arithmetical Paraphrase of the Lord’s Prayer’ printed in the Lewes Journal in July 1771, he may by then have reached a Deist position. Perhaps his anger against injustice had already led him to reject revelation and question the truth of what Noble had said in a 1767 sermon about ‘the wisdom of Christ’:

It is certainly proof of the wisdom of Christ that he did not at all interfere in civil matters or make such declarations in behalf of the common rights of universal mankind as could only have tended to draw down the whole fury of the secular power upon all his followers.

By the time he left Lewes in 1774 it is likely that Paine, never one to worry about drawing down fury, would have openly disagreed with this statement and with Noble’s conclusion that philosophy must always be ‘assisted by Revelation’.8

Conclusion

Which then had the greater influence on Paine as a young man — Wesleyan Methodism or Rational Dissent? John Keane is evidently convinced that it was Methodism. In a sub-section of his book entitled ‘The Methodist Revolution’ he considers the effects of Paine’s involvement with the Wesleyan movement. He contends that historians have misunderstood Methodism, wrongly seeing it as ‘a reactionary protest against Enlightenment reason and a movement that seduced its followers into conformism’. On the contrary, he says, Methodism ‘fed the modem democratic revolution in mid-eighteenth century England by offering a vision of a more equal and free community of souls living together on earth’ Although he admits that ‘the extent of Paine’s involvement with Methodism is uncertain’ he believes that it was primarily from this that the young man derived his egalitarianism, his passion for justice and his conviction that individuals were morally responsible for their own conduct. Several sentences begin with statements such as ‘Methodism demonstrated’, ‘Methodism showed’ or ‘Methodism convinced him’. Moreover it was Methodism that allegedly provided Paine with ‘the exhilarating view, traceable to the Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminus, that Christ’s sacrifice and atonement meant that all men and women might be saved’.

‘You are steeped in sin, and there is nothing in you which merits God’s goodness’, the young Paine may have told his nervous and spellbound congregations in Dover and Sandwich, rephrasing words from other Methodist preachers that he had heard in action. ‘Yet remember the new light of God’s grace shines equally upon the poor and the rich. God is ready to welcome you — all of you — as His children so long as you strive to attain His grace and live the holy life which allows you to enter into His Kingdom’.

But do these sound like the worst of a man who had been (at the age of seven or eight) ‘revolted, by a sermon on the Atonement and had ever since ‘either doubted the truth of the Christian system or thought it to be a strange affair’? Although the Wesleyan doctrine of the Atonement was more liberal and humane than that of the Calvinistic Methodists it is doubtful if it could ever have been acceptable to Paine, whom the whole idea of God sacrificing his own son was repugnant.9

Because of his distaste for the orthodox ‘Christian system’ it is likely that Paine responded positively to the heterodox preaching of Rational Dissenters such as Daniel Noble. Although, as Keane points out, Noble ‘preached Arminian views’, his Arminianism was very different from Wesley’s. While Wesley’s position was close to that of Arminius himself (as introduced into England by the Caroline divines), Noble’s was that of a later generation of Dutch Remonstrants, whose views had been introduced into England by Limborch and Locke. Having been steeped in Locke’s philosophy at Kendal academy, Noble was more concerned with enlightening men’s minds than with saving their souls. His Arminianism, to borrow a phrase from Geoffrey Nuttall, was not ‘of the heart but ‘of the head’.10

Some idea of what Noble’s preaching was like can be obtained from a sermon he delivered during Paine’s time in London, entitled ‘Religion, perfect Freedom’. It is full of references to such things as `the providence and moral government of God’, the ‘Sovereign Being who is able to make all things work together for good’ and the ‘laws of benevolence which are the true spirit of the Gospel’. ‘Is it not evident’, he asked, ‘that the pure and undefiled religion of Jesus bears a very friendly aspect to the cause of civil liberty?’ This is a very different tone than that of the average Methodist sermon with its heavy emphasis on sin and personal salvation. Is there not a foretaste here of what Paine was to write in The Age of Reason? Could not Noble’s preaching have helped to convince him that ‘the oral duty of man consists in imitating the moral goodness and beneficence of God’ and that ‘everything of persecution and revenge between man and man, and of everything of cruelty to animals, is -a violation of moral duty’? Apart from the reference to cruelty to animals, which shows Paine to have been far ‘ahead of his time’, the phraseology could have been lifted from almost any Rational Dissenting sermon.11

Was it not from the Rational Dissenters rather than the Methodists that Paine derived the belief that his religion was simply ‘to do good’? Is it not likely that, as Ernest ‘Payne suggested, his association with Daniel Noble was ‘of some importance for the young man’s intellectual and spiritual development’? Judging by ‘A Sketch of the Character of the late reverend and learned Daniel Noble’ published in The Protestant Dissenters’ Magazine some years after his death he sounds like a man after Paine’s own heart.

He had very enlarged ideas of the rights of others and was, upon principle, a thorough friend to the civil and religious liberties of all mankind. In conversation he was open and liberal, and at the same time serious and instructive.

By all accounts Ebenezer Johnston of Lewes was a man of similar temper. Could the author of The Age of Reason have found better mentors than these two very rational Dissenters?12

References

- T. Paine. The Age of Reason. Paris, 1794. 82-3.

- J. Keane. Tom Paine: A Political Life (1995). 46, 544 n.29; N. Cumock. Ed.. The Journal of the Rev. John Wesley, Vol.8 (1916), 3, in The Methodist Recorder, 16 August, 1906, 9.

- Keane, op.cit, 55, 60-1. E. A. Payne, ‘Tom Paine Preacher’, The Times Literary Supplement, 31 May, 1947, 267.

- Keane, op.cit., 62; Payne. back, W. T. Whitley, Seventh Day Baptists in England, Baptist Quarterly, n.s., Vol. 12 (1947), 265.

- Keane, op.cit., 62-3; W. T. Whitley, ‘Daniel Noble’, Baptist Quarterly, n.s., Val (1922), 137.

- J. M. Connell, The Story of an Old Meeting House, 2nd edn (1935), 64- 6; Keane, op.cit., 76-7.

- Connell, op.cit, 55-60.

- Keane, op.cit., 70; D. Noble, Religion, perfect Freedom: A sermon preached at Barbican. March 1, 1767, 25-7.

- Keane, op.cit., 45-9; Paine, The Age of Reason, 80-81.

- Keane, op.cit, 61; C. G. Bolam et. AL, The English Presbyterians (1968), 22-3; G. F. Nutthall, The Influence of Arminianism in England’, in, G. 0. McCulloch, ed., Man’s Faith and Freedom (1962), 46-7.

- Noble, op.cit, 19-20, 26-8; Paine, The Age of Reason, 116.

- The Protestant Dissenters’ Magazine, Vol.5 (1798), 441-2.

Dr. Jeremy Goring is a member of the Thomas Paine Society and is a former Dean of Humanities at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He is the author of, Bum Holy Fire: Religion in Lewes Since the Reformation, which was published by the Lutterworth Press in 2003.

Reprinted from the Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society.