France After the Terror: 1797-1802

By Joy Masoff

ABSTRACT: The intellectual and political sides of Paine have had their time in the spotlight. More scholarly attention needs to focus on Paine, the person, his connections, and his networks. Few publications have examined Paine’s intimate inner circles, and almost nothing has been written about Paine as a devoted confidante, much less as a family man. Underexamined in the entire Paine corpus is the story of Paine’s role as a surrogate father and grandfather during the long denouement of the Revolution in France and the years he spent living with Nicolas and Marguerite Brazier Bonneville and their four young boys. Paine’s deep relationship with the Bonnevilles lasted for more than 15 years. This essay studies Paine’s time with the Bonnevilles in Paris during the six years he lived with them, from 1797 to 1802, as Napoleon Bonaparte began his ascent to power and U.S.-France relationships floundered.

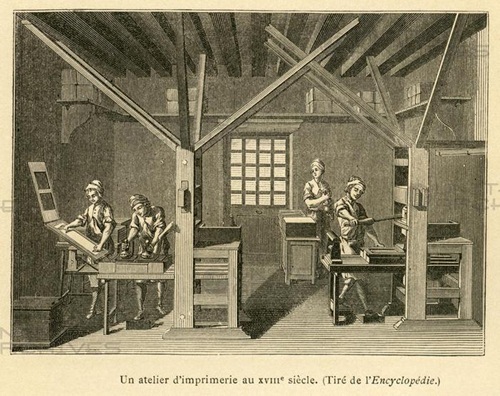

The impressive Théâtre-Français, affectionately called La Maison de Molière in honor of the French literary icon, is the world’s oldest established national theatre. In the late 1790s, the homes surrounding it were relatively new, and the residents relatively prosperous. The Left Bank was beginning to acquire its reputation as a bohemian and artistic mecca. The street directly north of the theater square was called the Rue de Theatre Français, and it was here that Nicolas Bonneville’s Imprimerie de l’Cercle Social occupied part of the ground floor at No. 4: here that Thomas Paine’s knock on the door, one April day, changed the trajectory of his life.

This new period in Paine’s life was transformative. In addition to fretting about the state of the world, he assumed a new role: godfather, surrogate grandfather, and family man. His absorption into family life adds a nuanced dimensionality to our knowledge of Paine. The Bonneville family was unique among Paine’s circles because their roles in his life were unique. Family became a part of Paine’s persona through their shared experiences of the revolution as ongoing unrest unfolded across Europe: through years of disruption and uprooting, and even the simple struggles of daily household existence. Several historians have dubbed Paine a “loner,” and missed this important connection. Paine’s inner circles were broader than mere political or pontifical associations, and far more than simply springboards for epistolary exchanges or impassioned editorializing. Friends and family changed Paine’s future.

WHO WERE THE BONNEVILLES?

Paine first met Nicolas Bonneville in the early, heady days of the French Revolution, after he faced sedition charges in England and arrived to take his seat as the delegate from Calais at the 1792 National Convention. Paine had already formed several firm friendships with friends of the Bonnevilles who were members of the Girondins—especially the Condorcets, the Brissots, and the Rolands.1 With these contacts came entry into several new networks, including L’Cercle Social, the benignly-named, initially-secretive organization that played an aggressive role in the Revolution as it unfolded. Paine’s induction into the Cercle, helmed by Nicolas Bonneville and the Catholic cleric, Claude Fauchet, firmly inserted him into the heart of French revolutionary activism.

Bonneville (1760-1828) was a writer, utopianist, activist, publisher, and editor of four newspapers, each aimed at a different demographic. He was part of a rarified coterie of political, philosophical, and theosophical thinkers of the time, and some historians regard him as a founder of the “modern revolutionary tradition.”2 His wife, Marguerite Brazier (1767-1846) was a proto-feminist and Cercle Social activist. The Bonnevilles were in the thick of Girondin politics until the rise of the Committee of Public Safety, which unleashed the Terror and led to the executions of many Girondist leaders. Paine was incarcerated, allegedly for being British, and almost died, abandoned by the U.S. Minister to France at the time, Gouverneur Morris.3 After Paine’s release from his imprisonment and long recovery, he came to live with the Bonnevilles, not sure how long he would remain. His years with the family humanized Paine, revealing a different dimension of a complicated man. The constant exchange of ideas between Bonneville and Paine— two utopianists separated by age and temperament— offers glimpses of the intergenerational inspirations that flowed in both directions and steadied Paine through this period of his life. These connections enabled the political Paine, the spiritual Paine, the scientific Paine, and the social Paine to flower in new ways. Imbued with a sense of safety that came from the warmth of his new living arrangements, Paine could focus on the many ideas crowding his thoughts.

Meeting Paine as a family man, in conjunction with his search for relevancy in the wake of the failure of France’s 1793 Constitutional Convention and his difficult imprisonment, discloses a scantily examined chapter in his life. Paine’s stay with the Bonnevilles lasted for six years, from 1797 to 1802, when Paine was finally able to return to the United States after Jefferson was elected president. Paine wrote several forceful pamphlets, and he certainly remained engaged in furthering of his cause for universal republicanism. Paine wrote tirelessly, constantly, and frequently defensively, particularly as Age of Reason continued to create blowback. Significantly, Paine was deeply invested in the triangulated political machinations of the United States, Britain, and France, as well as Bonaparte’s continued thrust into, and annexation of, regions across much of Europe. Paine’s output was largely reactive, rather than accretive. He was not building on radical new ideas, as he had with Agrarian Justice, but instead attempting to dismantle existing ones that conflicted with his own.

AS THE CENTURY ENDED

Despite the Enlightenment mantra that we are all created equal, societies are not, and their responses are unpredictable. Causality, complexity, and contingency all played roles in the events leading up to the Western Hemisphere’s revolutions and in the crumbling of their possibilities in France in the years that followed the Terror. The last five years of the eighteenth century saw tremendous turmoil in both the Atlantic world and the halls of governance in America. The Genêt Affair and the Jay Treaty had worsened Franco-American relations, and several events in the United States impacted Paine’s world: John Adams’s ascension to the U.S. Presidency; 1797’s XYZ Affair; and a declaration of what became known as the Quasi-War with France.4 It was during this period in America that Federalist hegemony in opposition to Democratic-Republican agrarianism exploded—both in the halls of Congress and across the Atlantic world— as slave revolts in the Caribbean, Napoleon’s incursions deeper across Europe, and diplomatic failures pushed the Western Hemisphere deeper into unrest.

A NEW HOME, A NEW NETWORK

The Bonneville-Paine connection was forged at the beginning of the Revolution, during the many socio-political gatherings of the post-Bastille, pre-Terror years. In addition to sharing common notions of freedom and an unflaggingly optimistic belief in a better future, Nicolas Bonneville’s fluency in English allowed Paine to speak “in a more familiar and friendly manner than to any other persons of the society.”5 On the April day that Marguerite Brazier Bonneville welcomed Paine into her home, she expected him to stay for a fortnight. Instead, he stayed on and off for six years. Many years later, in collaboration with Paine acolyte William Cobbett, Madame Bonneville recalled the statesman’s arrival and the many years spent under her roof.6 Her memoirs offer a fascinating picture of Paine’s time between James Monroe’s departure from Paris in 1797 and Paine’s final farewell to France in 1802.

It fell upon Madame Bonneville—with a newborn in her arms when Paine arrived—to look after her new houseguest. Two other boys scampered around the house: Louis, aged seven, and little Nicolas, just three-and-a-half. 8 Paine loved the children, especially the new baby, named Benjamin in honor of Ben Franklin. He nicknamed the infant “Bebia,” an endearment that stuck through late childhood. A little over a year after Paine’s arrival, a fourth boy, Thomas Paine Bonneville, added to the bustle of an already hectic household and became Paine’s godson. But who was Madame Bonneville?

Love and marriage did not necessarily go together in pre-revolutionary France, or, for that matter, in much of Western Europe. Marriage often dragged the heavy baggage of laws of inheritance, dowries, dotage, and paternity behind it. For families with any wealth, it involved elaborate financial documents with multiple pages of fiscal foreplay—more business arrangements than bonds of love: a mariage de convenance. Worse still, it could involve conjugal cruelty and forced unions. Within the Catholic Church, there was no escaping an unhappy, or worse, a brutal marriage. In Suzanne Desan’s The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France, the author quotes the Comte d’Antraigue’s 1789 description of Old Regime marriage, not as a sacrament, but as “a sacrifice, a sacrilege.”9

During the revolutionary period, vigorous debates were held on how best to reform the conjugal system. Within the context of these discussions that we can best understand the union Marguerite Brazier entered into with Nicolas Bonneville and the life they began to create together. As a result, with the Enlightenment came newfound matrimonial freedom and a new framework that, to this day, informs the marital laws of many Western nations.

When Lyonnaise-born Marguerite Brazier— the now-orphaned daughter of an activist maître pâtissier—met Nicolas Bonneville, he had not yet found his true calling. He was alternately hyperfocused or unfocused, with a kind of intellectual attention deficit disorder that kept him veering from one passion to another. Was he a philosophe? A poet? A political theologian? A journalist, politician, linguist, historian? No matter the label, he assuredly believed that he had earned the right to call himself a full-fledged member of the Republic of Letters—as well as a citizen of Paris, which had anointed itself as the cultural capital of the world.

Meeting Marguerite sparked something new in Nicolas. If he were to be a husband, then the notion of matrimony demanded some of his scattershot attention. In 1792, he finally gathered all his thoughts on marriage—both personal and civic—and published Le Nouveau Code Conjugal.10 His ability to speak definitively on the subject owed much to his union with Marguerite. As a dyed-in-the-wool idealist, he would not have written this were his marriage a sham. The slender volume is at times frustratingly arcane, particularly in its theoretical discussions of a return to the monarchy. Should any new king only be permitted to marry a Frenchwoman?

In Le Nouveau Code Conjugal, traditional church vows were replaced with a more free-spirited pledge. “I declare, as a free man and good citizen, that I take _________as my friend and my wife.” The woman would reply “ as a free woman and good citizen, I take_________as my friend and my husband.” Friends and lovers: By combining ideals of citizenship with love and friendship, the Bonnevilles saw the culmination of a utopian ideal.

At the time, both believed that a civil union was an act of patriotism and Nicolas argued that religious marriages could only take place if the couple were first bound in a civil marriage—an oddly prescient idea that is the norm in America, where the statement “by the powers vested in me by the State of ________takes place at the end of most wedding ceremonies no matter how religious. But as radical as this ideology was, the union of Marguerite and Nicolas, proved as enduring as any marriage bound by ecclesiastical promises. As Paine settled into his rooms, he read reports of a new monarchist revival brewing, as Royalists emerged from their hiding places, eager to take advantage of the nation’s continued economic struggles to foment a new rebellion and a return to monarchical rule. This troubled Paine, so he sharpened his quill and began writing for Bonneville’s newspaper, Le Bien Informé.

Living with the Bonnevilles offered a healing atmosphere for Paine: the warm and boisterous embrace of family was something he had never experienced before. Bonneville quickly became the son Paine had never had, and Marguerite Brazier, his surrogate daughter-in-law. Every morning, Paine would sleep late, devour the local newspapers, and then seek out his genial host, journals in hand, to “chat upon the topiks [sic] of the day.”11 He wrote editorials for Le Bien Informé, and often found himself in the company of two of Bonneville’s great friends, Louis-Sebastien Mercier and Jean-Charles Nodier both book lovers and brilliant creative writers.

Mercier was a prolific playwright and one of the earliest writers of science fiction. He, like Paine, had served at the Convention, aligned with the Girondins, and also ended up in prison during the Terror, while Nodier, almost 40 years younger than Paine, represented a new generation of thought.12 He was a writer of contes fantastiques—tales of vampires and of the romantic monsters that were a hallmark of Gothic literature.13 Nonetheless, both Mercier and Nodier were political creatures. They spent a great deal of time with the Bonnevilles, exposing Paine to writers who were part of a burgeoning “romantic” movement in the arts that was sweeping across Europe.

Romanticism brought a way of seeing a new and rapidly changing world. Feeling was more important than thought, and introspection more important than exposition.14 The Romantics argued that human behavior was governed by passion, not reason, and we are left to wonder what Paine thought about this.

Bonneville’s newspaper, Le Bien Informé, was a work of serious journalism and was widely read in Paris. It covered politics, society, and literary events along with stock market and weather reports. In addition, Bonneville’s post-Terror printing establishment, Imprimerie de Cercle Social, offered a second journal: Vieux Tribune et sa Bouche de Fer, which was Bonneville’s philosophical playpen for his own idealistic visions, many of which read like mystical fever dreams. Bonneville also translated and published several of Paine’s political tracts, including Compacte Maritime—one of Paine’s last polemical pamphlets. 14 Paine’s association with Bonneville’s imprimerie and specifically Le Bien Informé gave him a platform, a voice, a degree of relevance, and, perhaps misguidedly, a sense of power—a bully pulpit from which he could preach about his ongoing obsession with the end of the British monarchy. Four significant areas occupied Paine as he ricocheted from politics to ombudsmanship to religion to science, and back again, often in the same day.

THE ATLANTICIST PAINE

I have been introduced to the famous Thomas Paine, and like him very well. He’s being vain beyond all belief, but he has reason to be vain, and for my part, I forgive him. He has done wonders for the cause of liberty, both in America and Europe, and I believe him to be conscientiously an honest man. He converses extremely well; and I find him wittier in discourse than in his writings where his humor is clumsy enough.15

—Theodore Wolfe Tone

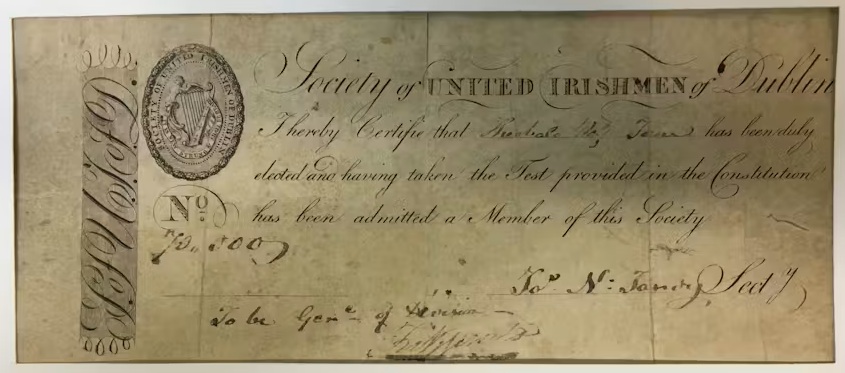

Theobold Wolfe Tone was an Irish revolutionary and a Paine admirer. Together with James Napper Tandy, in 1791, the two Irishmen founded the Society of United Irishmen, with the organization’s goal of “the abolition of bigotry in religion and policies, and the equal distribution of the Rights of Man through all Sects and Denominations of Irishmen.”16 Paine was an ardent advocate of Irish independence and worked actively for their cause throughout the entirety of his years in France, beginning in the early days of France’s revolution. He wrote several articles in Le Bien Informé lauding the United Irishmen and their leaders, and frequently socialized with both Tone and Tandy, who had come to Paris to rouse French support for their cause.17

Le Bien Informé frequently reported on Paine’s interactions with both men, as well as his associations with Scots agitator Thomas Muir.18 Paine believed that a corrupt British government was the greatest threat to peace at the time. It became an obsession for Paine, to the point where Great Britain, not Bonaparte’s increasing power grabs, were foremost on his mind. Irish independence was simply part and parcel of Paine’s grander view, and, to his thinking, the logical next steps after France’s victories in Belgium and the creation of a French alliance with the Dutch in 1795.19 This allowed Paine to foment a fever-dream of his own: an invasion of Great Britain.20

Both Paine and Bonneville had a shared flaw: what historian Thomas Walker called their relentlessly “exhilarating optimism.”21 Paine’s democratizing international liberalism dominated his activities at this point, yet it is a study in contradictions. He had a deep disdain for war-prone authoritarianism, yet conversely, a belief that military interventions were an acceptable price to pay for progress.22 But in Paine’s envisioned military, the incursions were won by small liberating armies—rather than large-scale invasions—and directed toward nations and states eagerly expressing a desire to transition from a monarchy to a republic.

Paine began authoring a series of articles for Le Bien Informé, urging an invasion of England.23 Returning to mathematical analysis as a weapon, he calculated everything from the military force needed to successfully effect an invasion to the cost of building a thousand gunboats. One month later, Paine penned a letter to the Directoire’s Council of Five Hundred, followed by a piece that appeared in Le Bien Informé the next day. In it, Paine championed an intervention entirely funded by contributions from fellow French Republicans. Paine proudly put his money where his mouth was, writing, “My economy permits me to make a small patriotic donation. I send a hundred livres, and with it all the wishes of my heart for the success of the descent, and a voluntary offer of any service I can render to promote it.”24

Throughout this push for invasion, Paine maintained polite relations with Bonaparte, who visited the Rue de Théâtre Français and even dined with the Bonnevilles. Who better to bring down Great Britain’s monarchy than the French general who was wreaking such havoc on Europe? Their initial meetings were cordial, and Paine, a sponge for praise, told his friend Joel Barlow that Bonaparte confessed to sleeping with a copy of Rights of Man by his bed. Many years later, Madame Bonneville remarked that Paine “was not satisfied without admirers of his success,” and at that point, Bonaparte indeed was. That admiration did not last. By 1802, according to a friend of Paine’s, whenever Paine and Bonaparte found themselves together at political gatherings, they would not speak. They simply glared at one another.25

Paine had been obsessively devising a British invasion plan, and shared it in a long and detailed letter to James Monroe written in 1797. He praised the efficiency of small, swift gunboats—“a vessel that can elude ships of war, for its object is not to fight but to elude and disembark”—to be deployed across the North Sea under the proper wind conditions to sneak down the British coast to launch an attack.26 Reading the minute details of Paine’s plan, the imaginary envisioning of an almost Viking-like offensive, and the swift crumbling of British monarchist resistance, seems nearly as dreamlike as Bonneville’s romanticist ramblings in Vieux Tribune et sa Bouche de Fer. An abortive attempt to liberate Ireland in August 1798, ended in disappointment one month later after a very short-lived Irish Republic.27 Curiously enough, although specifically warning against authoritarianism in government and condemning the restoration of special privileges based on wealth or caste, Paine at first felt little alarm at the rise to power of Napoleon. For Paine, the greatest of all enemies to the French people, internal or external, was the corrupt and autocratic British government. With his eye on Great Britain, he may have overlooked the potential threat posed by Napoleon to France, so focused was he on the problem of delivering a military defeat to his sworn foe.

THE SOCIAL PAINE

The house at No. 4 became Paine’s sanctuary, offering him a metaphorical “throne:”a place to hold court with some of the most influential scientists, politicians, warriors, and philosophers of the age. One role that Paine loved playing was ombudsman: the man with “connections.” He was always busily introducing a needy individual to the right person who could offer help. There was an “innocent Englishwoman trapped in France with a five-year-old child, longing to get home, who Paine assisted.”28 Paine connected Bonneville with a banker he knew to help prepare an loan application for Madame Bonneville to become the proprietress of a lottery office.29 In a remarkable two-column bilingual letter written by Paine and Bonneville, on shared pieces of paper, the men submitted a two-language petition to free Charles Este—the son-in-law of Paine’s close friend Robert Smith—who had been imprisoned.30

Paine even wrote to General Brune—a close friend of Bonneville’s and a key leader with part of Napoleon’s multi-placed strike forces—to say “I congratulate you, my dear and brave general, on your happy and glorious success in Holland,“ and then, still obsessed with the trampling of the British fleet, suggested that the Batavians would need to raise a new navy.31 “I have a friend, an American, who has been bred up to sea from his infancy, and is very desirous of serving under Admiral Dewinter. He is in the prime of life, brave, and a complete seaman.”32 Paine also maintained his lifeline to Fulwar Skipwith throughout his years with the Bonnevilles, facilitating help for the inventor Robert Fulton and many others.

Madame Bonneville, busy with proofreading and child-rearing, was assigned the role of “concierge” and charged with either allowing the visitors who flocked to her door to see Paine, or offering up “polite prevarications” as she put it, when she told them he was not in.33

Paine’s visitors included Tadeusz Kosciuszko, hero of the American Revolution, and Henry Redhead Yorke, a young British friend of Paine’s, who survived Madame Bonneville’s intense scrutiny the first time he came to visit. Yorke was an illegitimate Creole born to a British slave-owning plantation overseer in Barbuda and a free black Antiguan mother. At age six, his father brought him to England to be educated, bestowed a private income upon him, and saw to it that the lad went on to Cambridge, where he studied law. His Caribbean roots and mixed parentage placed Yorke in a position of liminality, and throughout his life, he never quite knew where his feet might best be planted.35

Sociable evenings capped off Paine’s days. He frequently visited with the Barlows and their houseguest, Robert Fulton, or dined with the Smiths. Other nights, Paine would walk over to an Irish coffeehouse on Condé Street. There, a drink in hand, he would hobnob with expatriate Irish, English, and Americans to take the pulse of politics in the U.S. and England.36 Constant exposure to people of many nationalities and all ages kept the cosmopolitan Paine energized and engaged even though he had no official role.

THE SPIRITUAL PAINE

The blowback from Christian church adherents to Age of Reason, Part the Second, was vitriolic. Nonetheless, Paine stayed the course, tirelessly defending his beliefs to whoever took him to task about them. Having gained his higher education in the company of learned people in his post-privateering London days, he found himself craving the company of likeminded deists, so Paine joined a relatively new society that began welcoming members in January of 1797. It was a lovely 20-minute walk from the Bonneville’s, past the glorious Saint Chapelle, and across the Seine to gatherings of the Society of the Theophilanthropists. Their dogma was simple: “les Theophilantropes croient a l’existence de Dieu, et a l’immortalite de l’ame,” which translates to “The Theophilanthropists believe in the existence of God and the immortality of the soul.”37 Rather than being an apostate, as he was constantly accused, the opposite was true. Paine’s faith was pure and deeply felt, as evidenced in a part of the speech he gave to the group.

The Universe is the bible of a true Theophilanthropist. It is there that he reads of God. It is there that the proofs of his existence are to be sought and to be found. As to written or printed books, by whatever name they are called, they are the works of man’s hands, and carry no evidence in themselves that God is the author of any of them. It must be in something that man could not make that we must seek evidence for our belief, and that something is the universe, the true Bible, — the inimitable work of God. 38

—Thomas Paine

The dismantling of the Christian Church by the Committee of Public Safety had left holes in the hearts of many French citizens. Throughout 1797, Paine wrote a series of letters defending his thoughts while challenging his critics to examine their own claims of personal godliness. In a pamphlet entitled Worship and Church Bells, Paine wrote to Camille Jordan, a royalist member of the Council of Five Hundred, and reminded him, “It is a want of feeling to talk of priests and bells while so many infants are perishing in the hospitals, and aged and infirm poor in the streets, from the want of necessaries.”39

Paine’s hackles were continually raised by the clinging rigidity of some of his colleagues to existing religious traditions. It is sometimes hard to tell which he was more determined to achieve: the spread of democracy or the global embrace of a new religion of humility and humanity.

In Prosecution of the Age of Reason, a pamphlet that Paine published in Paris in September of 1797, he confronted Thomas Erskine, a lawyer who had once defended Paine in absentia at his trial for publishing Rights of Man, and who now, five years later, had taken a Burkean path, and chose to prosecute Thomas Williams, Paine’s British publisher of Age of Reason, Part the Second.40 Williams was found guilty and sentenced to a three-year prison term. “Of all the tyrannies that afflict mankind, tyranny in religion is the worst. Every other species of tyranny is limited to the world we live in, but this attempts a stride beyond the grave and seeks to pursue us into eternity,” wrote Paine.41

Bonneville and Paine shared another powerful spiritual bond. Both were intrigued by Freemasonry, but only as an abstraction. Despite allegations of initiation, no records of a single lodge in England, France, or the United States bear either Paine or Bonneville’s name, but both had seriously investigated the practice.42 In 1788, before Paine and Bonneville became close, Bonneville had written Les Jesuites Écossoise chassés de la Maçonnerie.43 In it, Bonneville dealt with a conspiracy theory that alleged that the Jesuits infiltrated Masonic lodges and had done the same thing to the medieval Templars.

The famed historian of the Revolution, Albert Mathiez, described the original gatherings of the Cercle Social as an offshoot of Masonic ideology, writing, “Bonneville, the smoky and bold spirit, [was] the Grand Chief.”44 Paine continued to march to his own spiritual drum and began amassing notes for his own study of Freemasonry.45

At the same time, Bonneville grew increasingly obsessed by the Bavarian Illuminati, who championed universal brotherhood and the pursuit of global peace through benevolent spirituality. Compassionate globalism was Bonneville’s guiding vision, which he expressed with a romantic’s passion-tinged pen. Paine shared his sentiments but wrote more clinically and scientifically. In L’Esprit des Religions, Bonneville had also championed the creation of a “united universal association” to settle global imbroglios, which he called “the supreme court of nations.”46 Paine had adopted that idea and included it in Agrarian Justice—both men envisioning what would one day become the United Nations. The two men, living under the same roof, working together at Le Bien Informé, socializing at a favorite café on the Rue de Marais, discussing literature and philosophy with other forward thinkers, and sharing in the antics of the Bonneville’s little boys, filled a deep ache in Paine’s soul.47

THE SCIENTIFIC PAINE

Politics, religion, and Paine’s occasional ombudsmanship were not enough. As he balanced a full plate of intellectual and social challenges, there was one cherished place of escape for him. When he left America for France in 1787, he created and carried models of his iron bridge. Now, almost 10 years later, living with the Bonnevilles, he had the time to focus on more than party politics and insurrections. Paine resumed his obsession with his arched iron bridge and transformed Bonneville’s study into what he began to call his “work-shop.”49 Adding to the din of crying babies, the thrum of the presses on the first floor, and the shrieks of rambunctious children running through the hallways, came the hammering of mallet against metal late into the night. Paine had returned once more to the world of physics and the parameters of engineering: the certainty that came with the laws of nature.

One of the reasons Paine slept late most mornings was that he stayed up late into the night. Madame Bonneville recalled, “He employed part of his time, while at our house, in bringing this model to high perfection…This was most pleasant amusement for him.”50 The blows of a sledgehammer were now added to the soundtrack of the Bonneville home, but the good-natured Bonnevilles accepted the eccentricities of their guest.

Paine especially welcomed the company of fellow scientists. A frequent visitor to Paine’s workshop was Robert Fulton, one of the masterminds of the steamboat. As a 12-year-old growing up in Pennsylvania, Fulton had met Paine’s Revolutionary wartime friend William Henry, the munitions-maker who had built a giant testing lab to explore steam power. Putting engineering aside in favor of art, Fulton began his career as a portraitist but found himself increasingly distracted by the lure of invention.

He began by improving the functioning of devices to cut marble, dig ditches, and twist rope, but like Paine, he was fascinated by river crossings and experimented with devising a method to make prefabricated iron bridges.51 He grew interested in the construction of canals, particularly a design with no locks, which initially led to his journey to France. There, he forged a friendship with Paine and his great friends, the Barlows.

Joel Barlow also shared Paine and Fulton’s fascination with the mechanical arts and took the younger man in as a full-time, long-term guest, whom he affectionately called “Toot.” Together, one of their favorite topics was the notion of submarines, so Fulton submitted a radical plan to the Directoire. He eventually offered a self-funded submarine that he named Nautilus for the purpose of attacking British warships using what he called “torpedoes.”52 His reward for any successes would be a bounty for each ship destroyed, based on the number of guns on board. Over the next few years, it is likely that Paine, Barlow, and Fulton talked about Fulton’s submarine, which was eventually built and proved operational. It was during these gatherings that Fulton became a political disciple of Paine’s, adopting a kindred ideology, believing that with France’s help, Britain’s monarchical government would eventually be overthrown.

During his years with the Bonnevilles, Paine worked diligently on plans for an improved crane and a machine to more efficiently plane wood, which he then used in building newer iterations of his bridge model. In 1801, writing from Paris to his friend, now president, Thomas Jefferson, Paine evoked the third law of Galilei-Newtonian mechanics, describing a self-propelled automotive carriage with wheels that were propelled by small bursts of exploding gunpowder.53 His rapture at the ability to affect motion controllable by man rather than nature, i.e. wind and running water, was intoxicating. Paine saw the limitations of a steam engine as “impracticable, because…the weight of the apparatus necessary to produce Steam is greater than the power of the Steam to remove that weight, and consequently that the Steam engine cannot move itself.”54

Paine thought outside the box with an iteration of a combustion engine. “When a stream of water strikes on a water wheel it puts it in motion and continues it. Suppose the water removed and that discharges of gunpowder were made on the periphery of the wheel where the water strikes would they not produce the same effect?”55 How glorious, Paine thought, that an agent of death could be a pathway to a better future. He likened it to a poison that suddenly had the potential to cure instead of kill.

With the end of the one-term presidency of John Adams in 1800 and the ascension of Thomas Jefferson, Paine’s old friend Robert R. Livingston was named the seventh U.S. Minister to France. He arrived in Paris in December of 1801 and called on Paine several times. Madame Bonneville remembered that “One morning we had him at breakfast, [Charles] Dupuis, the author of the Origin of Worship, being of the party; and Mr. Livingston, when he got up to go away, said to Mr. Paine, smiling, “Make your Will; leave the mechanics, the iron bridge, the wheels, etc. to America, and your religion to France.”56

THE LAWS OF THE SEA

Paine and Bonneville both shared visions of a global peace and a universal brotherhood. Both men had written about it: Paine in Agrarian Justice and Bonneville, five years earlier, in L’Esprit de Religions. Paine was still impacted by his long-ago privateering experiences, still obsessed by oceanic inter-dependencies, and still angered by the Jay Treaty, so he gathered several articles and letters he had penned and put them together into a new pamphlet, Compact Maritime, which Bonneville translated into French and printed in 1800.57 An English version emerged the following year.58 The first part, “Dissertation on the Law of Nations,” was a condemnation of treaties, which “besides being partial things, are in many instances contradictory to each other.”59 Paine applauded the Armed Neutrality pact, earlier proposed by Russia and signed by most of the maritime commercial nations of Europe stating, “neutral ships make neutral property,” but Tsar Paul’s death precluded its enactment. Why, Paine wondered, if this step could be taken, were there no international laws when it came to the seas?

Bonneville was a philologist. He loved words, loved analyzing them, loved dissecting them down to their ancient roots. Paine had absorbed this habit and proceeded to autopsy the word “contraband” in the first part of Compact Maritime. If the Western world’s economy was driven by commerce, nations could not simply define contraband as they saw fit. The word in itself was meaningless. This was Paine’s first common sense stepping-stone to calling for the creation of international maritime protocols. Part II, “On the Jacobinism of the English at Sea,” was directed toward neutral nations. It was a call to action—a demand that nations assert their “rights of commerce and the liberty of the seas.”60 Paine pointed to the fact that Britain’s power came from its commerce and not from land resources, “hence, upon external circumstances not in her power to command.”61 That made the nation vulnerable in his estimation. Part III spelled out Paine’s 10- part proposal for an international trade agreement, based on oceanic safe spaces. If all the neutral nations of Europe, together with the United States of America, entered into an association to suspend all commerce with any belligerent power that molested any ship belonging to the association, England would either lose her commerce or be forced to consent to the freedom of the seas. Commerce, Paine pointed out, was England’s Achilles Heel. Paine’s time with the Romantics led him to pen a very flowery, Bonneville-like conclusion. “…we see France like the burning bush, not only unconsumed, but erecting her head and smiling above the flames. She throws coalitions to atoms with the strength of thunder—Combat and victory are to her synonymous.”62

BONAPARTE’S REVENGE

Combat and victory were also words synonymous with Napoleon Bonaparte’s incursions across Europe and into Africa. His meteoric rise from a Corsican expat to military wunderkind came to some degree through a series of fortuitous patronages. He had identified with the Robespierrists during the revolution, but somehow survived the taint of that association to catch the eye of Paul Barras, President of the Directoire, in 1795. During France’s protracted wars, Bonaparte’s ongoing military successes made him a hero.

During Paine’s time living with the Bonnevilles in France, Bonaparte made several visits to No. 4 Rue de Theatre Français and made a favorable impression on both Paine and Bonneville as Paine tried to convince the General that a full-throttled invasion of Britain was achievable. There were three meetings arranged with the Irish Republicans and Bonaparte, in which Bonneville served as a translator, but little came of the efforts.63 Bonaparte instead turned his attentions to Egypt, and Ireland was forgotten.

The seventeenth of Fructidor (September 3, 1797) was a landmark day in France. A coup d’état backed by military force, purged royalist and counter-revolutionary elements from the government, and gave emergency powers to the members of the Directoire. In response, Paine began penning a pamphlet, To the People of France and the French Armies, analyzing the progress of the Republic, and acknowledging that the crisis was a result of the “darksome manoeuvres of a faction.”64 He cited historical precedent for martial law to avoid bloodshed and to restore tranquility, perhaps as much to calm his readers as himself. In 1799, after a string of military victories, Bonaparte declared himself the First Consul of France, which led to a fast-growing disenchantment on the part of both Paine and Bonneville. Napoleonic France was a betrayal of the democratic values that so many had sacrificed their lives to obtain.

Bonneville had been growing increasingly critical of the government through his editorializing in Le Bien Informé, and one day he went too far. He skewered the frequently silent Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyés, one of the members of the Directory, after Sieyés went to Prussia on a state visit, writing, “If there were organized in Berlin a club of mutes, [he] should be named president, the dean of silent men.”65 The order came down to cease publishing, but Paine—always anxious to insert himself in the defense of the oppressed, wrote to the Directory and assured them that Bonneville was “honest” and “uncorrupted…a very industrious man—a good father, and a good friend.”66 Paine’s appeal worked, but only temporarily. Bonaparte was also monitoring Bonneville (and by extension Paine) as a potential enemy of the government.”

Soon after the Coup of 18 Brumaire—the day Bonaparte declared himself First Consul of the French First Republic—Bonneville likened Napoleon to Oliver Cromwell—a brutal autocrat who had orchestrated a genocide in Ireland over religious freedoms in 1649. In response, his presses were confiscated, and Bonneville was soon taken away and imprisoned. He would be silenced for several years.67

Paine had the good sense to leave town, head for Dieppe on the coast, and then on to Bruges to stay with Joseph Van Huele, a former inmate at the Luxembourg, who had cared for Paine during his almost fatal illness.68 Paine described Van Huele as his “particular friend” in recognition of the terrifying bond they shared after Joseph’s brother, Jean-Othon Van Huele, was hurled from a top-floor window, as Paine and the Belgian watched in horror.69

THE ROAD HOME

Paine had made his disaffection with Washington well known after his liberation from the Luxembourg, and it had cost him dearly. His opinion of John Adams was even worse (and certainly there was nothing but overt contempt in Adams’ opinion of Paine). Not holding back, Paine dubbed Washington and Adams, “Terrorists of the New World.”69 So when news finally reached France of Jefferson’s ascent to the U.S. presidency, he rejoiced, knowing he would be able to return to the place he called his true home.70 In March of 1801, Thomas Jefferson took the oath of office as president. A year earlier, the Treaty of Mortefontaine was signed, ending the Quasi-War, which gave Paine the opportunity to arrange for a safe journey across the Atlantic. Jefferson tried to send an official U.S. ship to carry Paine home, but Federalist opposition in the press created too much of a stir.

Finally, a ship was found courtesy of a Connecticut sea captain that Paine was friends with and a departure date set: September 2, 1802. A few days before Paine was due to leave, he dined with the Smiths one last time, and after a festive evening, he remarked that he had nothing to detain him in France; “for that he was neither in love, debt, nor difficulty.”71 During his lengthy imprisonment, Lady Charlotte Smith had exchanged poetry with Paine, he writing from “The Castle in the Air,” and she replying from her “Little Corner of the World.” She fixed her gaze on him and remarked that it was ungallant to say such a thing in the company of women. In reply, Paine jotted off one final ditty to his cherished friend, called “What is Love?” In its first stanza, he wrote:

It is that delightsome transport we can feel

Which painters cannot paint,

nor words reveal,

Nor any art we know of can conceal.

Canst thou describe the sunbeams

to the blind,

Or make him feel a shadow with his mind?72

But what of Madame Bonneville? Paine had often talked of the family coming to America, but the choice to leave France was not so easy for Madame Bonneville. She was left with four young boys and no means of support other than the charity of her husband’s father in provincial Evreux. Should she stay in France, or take advantage of Paine’s offer to care for her sons until her husband might be freed? Many years earlier, she had chosen dislocation, leaving her native Lyon and her siblings when she was barely 18 to travel to Paris in search of adventure. But Lyon was a few hundred kilometers away, not across an ocean. A decision had to be made. Choosing to protect her husband’s future reputation, she evasively recalled in her later memoir, “Some affairs of great consequence made it impracticable for Mr. Bonneville to quit France…it was resolved, soon after the departure of Mr. Paine for America, that I should go thither with my children, relying fully on the good offices of Mr. Paine, whose conduct in America justified that reliance.”73

On September 2, 1802, with his stalwart friend Thomas “Clio” Rickman by his side to wave farewell as he sailed away, the men arrived at Havre-de-Grâce. Two British friends, Francis Burdett and William Bosville, bestowed a £500 gift upon Paine to help him settle in when he finally arrived in America.74 It was not until October 30 that he finally sailed into Baltimore harbor after a treacherous crossing. He had been away from his adopted country for 15 years. He was 63 years old and worn by age, maltreatment, and disappointment—heartsick over the continuing sparring of warring political parties in America—tired of what he saw as the Federalists’factionalism, and the failures of some of the Atlantic revolutions. Still, as it has been said, “hope is optimism with a broken heart.” So Paine, always the eternal optimist, dug deep, believing that he still had the power to effect change.

THE PATH AHEAD

At the same time that Paine arrived in America, there were enormous changes afoot across the great swath of New France—the vast tracts of land that lay to the west of the Mississippi River.75 In October 1802, Spain’s King Charles IV signed a decree transferring the territory to France, while Spanish agents in New Orleans, acting on orders from the Spanish court, revoked U.S. access to the port’s warehouses. New Orleans was well on its way to becoming one of the busiest slave markets in America by then. Paine had thoughts on the topic and wrote to Jefferson two months after he arrived back in America from France.

Spain has ceded Louisiana to france and france has excluded Americans from N. Orleans and the Navigation of the Mississippi – the people of the western territory have complained of it to their government, and the governt. is of consequence involved and interested in the affair. The question then is, What is the best step to be taken first.76

—Thomas Paine

Perhaps he could convince Jefferson to offer to purchase all the Louisiana Territory for the United States: not just the Port of New Orleans. He believed he understood the mindset of the French government in a unique way. Perhaps there was even an official role for him. Paine was not finished: There was still work to be done.

THIS IS THE FIRST PART OF A TWO-PART ESSAY

ENDNOTES

- The group that Brissot, Roland, and Condorcet belonged to, were known as the Girondins, because many of them were from Bordeaux in an area known as the Gironde. They were politically moderate with a specifically nationalistic viewpoint. Their opposition were often called the Montagnards, who had earned that somewhat sarcastic name—the Mountain—because they sat in the higher rows of the chamber where the Assembly met. The Montagnard’s interests were more focused on Paris and more radical.

- See Gary Kates, The Cercle Social, The Girondins, and the French Revolution, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985).

- Morris disliked Paine, and was happy to have him locked away. The recall of Morris in 1704, and his replacement with James Monroe saved Paine.

- The Directory needed money to continue funding Bonaparte’s European incursions, and many French politicos were angry that John Jay allied with Britain in 1794, especially since The U.S. still owed France repayments for loans from the War of Independence. In 1796, France issues an order allowing for the seizure of American merchant ships.

- The Cobbet Papers in Moncure Daniel Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, Vol. 2, Appendix A. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), 429-460

- William Cobbett was an Englishman who went from hating Paine, to becoming an ardent admirer. After Paine’s death, Cobbett and Madame Bonneville began collaborating on a homage to Paine and there are many manuscript notes prepared by Madame Bonneville in which she shares her memories. These were eventually included in “The Cobbett Papers” that were added to Conway’s Life of Thomas Paine.

- Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, Vol 2, 443.

- A fire at the Paris city archives destroyed all records of births, deaths and marriages. None of the boys were baptized in the Catholic Church so no records exist there. Benjamin Louis Eulalie (Bebia) was born April 14, 1797, and little Nicolas was born on December 5, 1793. These are the only two officially verified birthdates because we know Benjamin’s birthdate from his application to attend West Point when he was a teenager and Nicolas—who had been too frail to travel to America—from his death certificate when he was 15. Louis and Thomas’s ages (but not dates of birth) were cited on the ship’s manifest when Madame Bonneville sought refuge in America in 1802.

- Suzanne Desan, The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 15. Desan writes, “if the state was now to be rooted in a contract freely chosen by the people, then marriage too, should rest on the free choice and contract of individuals.”

- Nicolas Bonneville, Le Nouveau Code Conjugal: Etabli sur les bases de la Constitution, et d’après les principes et les considérations de la loi, (Paris: L’impremier du Cercle Social, 1792).

- Conway, Life of Thomas Paine, Vol 2, 443.

- Louis-Sebastien Mercier (1740-1814) was a venerated playwright and his science-fiction novel, L’An 2440 was groundbreaking. Jean-Charles Nodier (1780-1844) was a book-lover from a young age. A librarian, he was also an ardent Romanticist and eventually gained fame for his Gothic novels.

- Maurice Cranstoun, The Romantic Movement, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing,1994), 11.

- Paine had fleshed out these ideas in a series of letters to Thomas Jefferson prior to the pamphlet’s publication

- Theobold Wolfe Tone, The Autobiography of Theobold Wolf Tone, Vol II, (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1893), 189.Wolfe Tone (1763-1798) was a cofounder of the United Irishmen, and an officer in the French army under General Hoche, who led an assault on the Irish Coast in 1796 which failed due to bad weather. A second attempt in October 1798 also ended badly, with Tone captured and imprisoned. He killed himself rather than being hanged.

- Nancy Curtin, The United Irishmen: Popular Politics in Ulster and Dublin, 1791–1798.(Oxford: Oxford University Press,1999), 24.

- James Napper Tandy (1739-1803) was also a co-founder of the United Irishmen and a friend of Thomas Paine’s, living in Paris at the time Paine was articulating an invasion plan of attack against Britain.

- See Ann Thomson, “Thomas Paine and the United Irishmen,” Persee: Études irlandaises, no.16-1, (1991), 109-119.

- A revolt in the Netherlands between 1794-1795 led to the birth of the Batavian Republic as a “satellite” republic under French auspices. For enemies of Great Britain, that belief was that the alliance, which had created a long stretch of coastline, as far south as the Pyrenees, would offer control of shipping, banking, and other resources through the combined fleets of two maritime powers against British trade and sea power.

- Alfred Owen Aldridge, “Thomas Paine’s Plan for a Descent on England.” The William and Mary Quarterly 14, no. 1 (1957), 74–84. Through France’s alliance with the Netherlands, the French now had a large stretch of coastline on the North Sea from which to launch a possible invasion. The formation of the Batavian Republic in 1795 took place when the Dutch Stadtholder was overthrown and a French “sister state” was established.

- Thomas Walker, “The Forgotten Prophet: Tom Paine’s Cosmopolitanism and International Relations,” International Studies Quarterly, 44 no.1 (2000), 166.

- Walker, “The Forgotten Prophet,” 51

- Le Bien Informé, Paris, Frimaire, and 25 Frimaire, An VI (December 14, 1797. Biblitoteque National de France

- Le Bien Informé, January 28, 1798.

- Henry Redhead Yorke: Letters from France, in 1802, (Volume 2, London: H.D. Symonds, 1804), 339.

- Thomas Paine to James Monroe, “Observations on the Construction and Operation of Navies with a Plan for an Invasion of England and the Final Overthrow of the English Government,” 1797. Library of Congress.

- About 1,000 French soldiers, under the leadership of General Humbert staged a successful landing in County Mayo on August 22. There were three attempted invasions that summer, but none were successful.

- Thomas Paine to Citizen Peyel, 9 Ventoise, An 3. BNF

- On October 26, 1797, Nicolas Bonneville wrote to banker Jean-Frédéric Perregaux, a friend of Paine’s, to borrow money to purchase, with government authorization, a lottery office that would be operated by “the mother of his children.“ Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris.

- Thomas Paine/Nicolas Bonneville to Senator Garat, 7 Nivoise, An 9, (December 27, 1800), Iona College/ Thomas Paine Archives.

- Thomas Paine to General Brune, November 1799. TPHA

- Thomas Paine to General Brune, November 1799. TPHA

- Paine to Brune, November 1799.

- The Cobbett Papers in Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, Vol. II, 443.

- For more on Yorke, see Amanda Goodrich, Henry Redhead Yorke, Colonial Radical: Politics and Identity in the Atlantic World (1772-1813), (London: Routledge, 2019.) He met Paine in late 1792 as a presenter for the Society for Constitutional Information to the National Convention, where he mixed with the British expatriate community, and witnessed the revolution first hand.

- John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life, (London: Bloomsbury, 1996), 438.

- Thomas Paine, Religious Year of the Theophilanthropists: or Adorers of God and Friends of Man, 2nd edition, John Walker, trans. (London: Darton and Harvey, 1797; For more, see Henri Gregoire’s “Histoire des Sectes,” tom. I., livre 2

- Thomas Paine, A Discourse Delivered by Thomas Paine, at the Society of the Theophilanthropists, at Paris, 1798.

- Thomas Paine to Camille Jordan, “Worship and Church Bells,” 1797. TPHA.

- Thomas Paine, A Letter to Mr. Erskine, September 1797. TPHA

- Thomas Paine, A Letter to Mr. Erskine, September 1797. TPHA

- Many historians assert that Bonneville was a Mason, but he was not. Bonneville offered a debt of gratitude to the “very dear and very respectable” Loge de la Réunion des Etrangers, but never joined.

- Nicolas Bonneville, Les Jesuites Écossoise chassés de la Maçonnerie, et Leur Poignard Brisé par les Maçons, (Paris: Orient de Londres, 1788.) Bonneville fascinated by the Bavarian Illuminati, and wrote L’Esprit de Religion in response to that movement.

- Isabelle Bourdin, Les Sociétés Populaire a Paris Pedant La Révolution (Paris, 1910), 159, quoting Albert Mathiez, Le Club des Cordeliers pendant the la crise de Varennes et la massacre du Champs de Mars.(Geneva:Slatkine, 1975).

- After his death, Madame Bonneville edited out some of Paine’s more pointed anti-Catholic sentiments and had printed, On the Origin of Freemasonry, (New York: Elliot and Crissy, 1810.)

- Nicolas Bonneville, L’Esprit de Religions, (Paris: Imprimerie de le Cercle Social,1793), 159-160

- Paine grew up as an only child after his sister died in infancy. His first wife, Mary Lambert, died in childbirth, and he separated from his second wife, Elizabeth Ollive, having never consumated the marriage.

- Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 445.

- Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 445.

- Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 445.

- Alan Rems, “Man of War,” Naval History, Volume 25, No. 4, July 2011. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history magazine/2011/july/man-war

- Rems, “Man of War.”

- Cobbett wrote, “A machine for planing boards was his next invention, which machine he had executed partly by one blacksmith and partly by another. The machine being put together by him, he placed it on the floor, and with it planed boards to any number that he required, to make some models of wheels. Mr. Bonneville has two of these wheels now. There is a specification of the wheels, given by Mr. Paine himself. This specification, together with a drawing of the model, made by Mr. Fulton, were deposited at Washington, in February 1811; and the other documents necessary to obtain a patent as an invention of Thomas Paine, for the benefit of Madam Bonneville.”

- Thomas Paine to Thomas Jefferson, “On the Means of Generating Motion for Mechanical Uses,” 1801, LOC

- Thomas Paine to Thomas Jefferson, “On the Means of Generating Motion for Mechanical Uses,” 1801, LOC

- The Cobbett Papers in Conway, 456. Dupuis’s work was a study of comparative religions based on the thesis that argued that all religions have a common origin, which can be traced back to the worship of the sun, moon, and stars.

- Thomas Paine, Pacte Maritime adresséaux nations neutres par un neuter, (Paris: Imprimerie–Librairie du Cercle Social, 1800).

- Thomas Paine, Compact Maritime, (City of Washington: Samuel Harrison Smith, 1801).

- Paine, Pacte Maritime, 4

- Paine, Pacte Maritime,11

- Paine, Compact Maritime, 24. The Fourth part of Paine’s work was a sarcastic analysis of the decisions of the judge of the English Admiralty

- Paine, Compact Maritime, 24. The Fourth part of Paine’s work was a sarcastic analysis of the decisions of the judge of the English Admiralty

- A petition from Bonneville to Napoleon reveals that he served as an interpreter during three meetings of General Bonaparte in 1797 with the United Irish chief. Arch. nat. F7 4286 dos.16.

- Thomas Paine, To the People of France and the French Armies, TPHA. (In Foner, Complete Writings, 2.605).

- Le Bien Informé September 17, 1798 66F7/8083/1196, Archives Nationale, Paris

- Le Bien Informé September 17, 1798 66F7/8083/1196, Archives Nationale, Paris

- Bonneville was imprisoned for having hidden Augustin Barruel in his home, under the guise of hiring him as a copyeditor. But Barruel had described Bonneville as an “impudent continuator of the nefarious job undertaken by Voltaire and his acolytes,” in Augustin Barruel, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire du Jacobinisme, 2nd ed. (Hamburg: Fauche, 1803), 2:275–301.

- “De filosoof Thomas Paine en zijn Brugse vriend Joseph Van Huele,” Bruge die Scone 4 (1993).

- Thomas Paine, “To the Citizens of the United States” (Letter III), 29 November 1802, in Complete Writings, 2:918, 920; “To the Citizens of the United States” (Letter VI), 12 March 1803.

- Beginning in October 1800, Paine wrote a series of letters, that culminated with his essay, Compact Maritime. In March, 1801, Jefferson offered Paine transportation on a U.S. ship, but Paine learned that his old friend, Robert Livingston, would be Jefferson’s minister to France, so decided to wait for Livingston’s arrival, hoping that he might be offered an official government role.

- The Cobbet Papers, 446

- Thomas Paine to Mrs. Robert Smith, “What is Love,”1800. TPHA

- The Cobbet Papers, 446-447

- Mark Philp, Thomas Paine: Very Interesting People, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 80. Burdett (1770-1844) was an English reformist politician who championed universal male suffrage. Bosville (1745-1813) was an extremely wealthy eccentric. He fought against the Americans during the War of Independence but left the battle impressed with the republican ethos. He was an ardent Whig and a very close friend of Paine’s friend John Horne Tooke. He and Burdett frequently socialized together.

- These territories were originally the dominion of France, but in 1762, after the signing of the Treaty of Fontainbleau the Francophile citizens of the region learned that they were now subjects of Spain. The entire Mississippi River Valley passed from Louis XV to his Spanish cousin Charles III as part of a secret pact at the end of the Seven-Years War, but this political sleight-of-hand changed little for the residents. French was still the Lingua Franca of the region.

- Thomas Paine to Thomas Jefferson, December 25, 1802, Library of Congress.