By Sybil Oldfield

Introduction.

Putting the world to rights: The presumptuous audacity of Thomas Paine.

How dared Thomas Paine, a man whose formal education had ended at thirteen (Gilbert Wakefield, Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge, would call him ‘the greatest ignoramus in nature’), a man who had failed as a skilled craftsman, as a teacher, as a shopkeeper, as a street preacher, as a petty customs official in the Excise, dismissed more than once and a sometime debtor and bankrupt, how dared such a nobody, such a non-achiever even dare to think about the ends and means of government, about the basis of a just society, about the meaning we can give life? Some of the fundamental questions that Paine pondered and tried to answer were:

Are humans essentially anti-social animals, whose lives are, in the philosopher Hobbes’ words, just ‘nasty, brutish and short’?

Do we have to be ruled by some absolute, hereditary, hierarchical authority backed by force?

Is humanity capable of instituting an alternative to war?

Is Christianity the only true religion?

Is any religion true?

But Thomas Paine did not merely articulate such fundamental questions in his secret thoughts, he also talked about them and dared to write about them. Think of his audacity when he, an almost penniless, recently very sick, immigrant Englishman, not long off the boat, started telling the people of North America in print what they should all now do, first in relation to slavery (they should abolish it) and then in relation to Britain. He called on Americans to revolt against his own country, and even called it just ‘Common Sense’ for them to do so.

Or think how Paine, a few years later, dared to take on Edmund Burke, Burke, the graduate of Trinity College Dublin, former barrister at the Middle Temple, former Private Secretary to the Secretary for Ireland, and then Private Secretary to the Prime Minister and himself an MP. Paine told Burke that his reactionary championing of the ancient regimes of Europe after the fall of the Bastille was wrong. His answer to Burke in Rights of Man was a trumpet call to ‘begin the world anew’: the British should abolish the hereditary principle of monarchy and aristocracy and substitute a just redistribution of wealth through graduated income tax.

Paine did not engage only Burke but also with many other dominant spirits of his age, including Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, General Lafayette, Danton, Condorcet, Marat, even Napoleon. In his dedication of the first part of Rights of Man to George Washington, Paine hoped that its principles of freedom would soon become universal. In his Dedication of the second part of his Rights of Man to General Lafayette, he urged the latter to export the French Revolution to the whole world – above all to the despotism of Prussia.

Finally, in his Age of Reason, Paine took on God Himself and denied the divinity of Christ whom he called simply ‘a virtuous and amiable man’: ‘I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish Church, by the Roman Church, by the Greek Church, by the Turkish Church, by the Protestant Church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church’.

Mocked and caricatured in his own day as presumptuous little ‘Tommy Paine’, where on earth did Paine get this unexampled, defiant audacity from? But it was not unexampled. Paine did have exemplars for ‘speaking Truth to Power’. Ultimately, behind Thomas Paine, I suggest, there lies the Epistle of James: the most radical, angry exhortation to social justice in the whole New Testament. Let me remind you:

…[Be] ye doers of the word, and not hearers only… My brethren, have not the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ… with respect of persons.

If there come into your assembly a man with a gold ring, in goodly apparel, and there come also a poor man in vile raiment and ye have no respect to him that weareth the gay clothing, and say unto him, sit thou here in a good place; and say to the poor, Stand thou there, or sit here under my footstool:

Are ye not then partial in yourselves,… [Ye have despised the poor…[If] ye have respect to persons ye commit sin;… What doth it profit, my brethren, though a man say he hath faith, poor…[If] ye have respect to persons, ye commit sin;… What doth it profit, my brethren, though a man say he hath faith, and have not works? Can faith save him? And if a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, And one of you say unto them, Depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled; notwithstanding ye give them not these things which are needful to the body; what do it profit? Even so faith if it hath not works, is dead … For, as the body without spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead also…

Go to now, ye rich men, weep and howl for your miseries that shall come upon you. Your riches are corrupted, and your garments are moth-eaten. Your gold and silver is cankered; and the rust of them shall be a witness against you… Ye have heaped up treasure together for the last days. Behold, the hire of the labourers who have reaped down your fields which is of you kept back by fraud, crieth, and the cries of them which have reaped are entered into the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth’.

That had been written, perhaps by Jesus’s brother, 1,700 years before Paine’s birth but was available to him of course as a young child and a young man, in the Authorised version of the King James English Bible. The Epistle of James would resonate repeatedly among the early Quakers and in Paine’s own writings.

Much nearer to Paine, both in place and time, as exemplars, were these early English Quakers – the Quakers of the recent persecution period 1650-1690. Moncure Conway, Paine’s first serious, sympathetic biographer wrote Iliad] there no Quakerism there would have been no Paine.1 Was he right?

Part One

Who were the Quakers?

Had there been no Civil War, or ‘Revolution’ as Paine himself called it, in England between1642 and 1651 there would have been no Quakerism, which began as a collective movement in 1652. The world had just been ‘turned upside down’ in Britain by that very recent war in which people had been asking – and killing each other over – fundamental questions about how to be a Christian and what kind of society Britain should be. The Parliamentarian ‘Roundheads’ believed they were fighting against royal tyranny and ungodliness; the monarchist Cavaliers believed they were fighting against mob anarchy and against hypocrites out to usurp power under the fig leaf of religion.

Each side, of course, believed very sincerely that God was on their side. And this English Civil War, called ‘The Great Rebellion’ by the royalist Cavaliers, and ‘The Good Old Cause’ by their Puritan Roundhead opponents, had actually been the English Revolution – culminating in the trial and execution of the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1645 and of King Charles 1 – only very recently, in 1649. The men and women who would be convinced and converted to Quakerism just three years later at the beginning of the 1650s had sympathised with the Puritan, Roundhead side.

Some (though not George Fox), had even fought for Cromwell and Parliament against the king. They saw themselves in the tradition of the Protestant Martyrs burned at the stake under ‘Bloody Mary’ a century earlier – for instance Margaret Fell, ‘the Mother of Quakerism’, born Margaret Askew, was believed by some, mistakenly, to be actually descended from the famous Protestant martyr Anne Askew. During the Civil War they had often called themselves ‘independents’. Once the war had been won by Cromwell’s New Model Army and the Parliamentarians, many of these self- styled ‘Independent’ men and women remained restless ‘Seekers’, looking for spiritual leadership that might help them towards personal and social salvation. They would walk or ride many miles to hear a preacher who, they had heard, was a true man of God. Hence that great assembly of about a thousand or more Westmoreland Seekers at Firbank Fell, above Brigflatts, near Sedbergh, in Whitson, 1652, who heard George Fox tell them: ‘Let your lives speak’. He told them they had no need of a church or parish priest, but that they should all live their Christianity, emulating the earliest ‘primitive’ Christians as a Society of Friends. The ‘Valiant Sixty’ among those who heard Fox, then attempted to do just that, spreading their message of ‘the inner light’ in every man and woman out from the North Down to London, South, West and East – to Norfolk, the county of Thomas Paine.

Although the Quakers’ creation of new congregations of ‘Friends’ in the 1650s came out of the spiritual turmoil of the Civil War, it was also a reaction against the brutal cruelty of that war. In fact George Fox had been moved to begin preaching a gospel of brotherly love already in 1646, right in the middle of the war. For is any war quite as terrible as the Civil War? – town against town, family against family, father against son, brother against brother, besieged women and children deliberately starved to death, prisoners deliberately mutilated and murdered after they have been promised pardon on surrender – and many other such atrocities – all in the name of ‘King and Country’ or else ‘For God and the People’. These very early Quakers were fired by a defiant, millenarian vision; they too wanted to turn the world upside down – but this time, unlike in the recent Civil War, by wholly non-violent means. Therefore immediately after the Civil War that had not brought about Jerusalem the Quakers preached and practised the alternative to war – non-violent resistance. Margaret Fell, the ‘Mother of Quakerism’ who would later marry Fox, wrote in 1660 to Charles II:

We who are the people of God called Quakers, who are hated and despised, and everywhere spoken against, as People not fit to live… We are a people that follow after those things that make for Peace, love and Unity… we do bear our Testimony against all strife and wars… Our weapons are not Carnal, but Spiritual.

George Fox, 1661, delivered to Charles II a ‘Declaration from the Harmless and Innocent People of God, called Quakers against all plotters and fighters’.

The Quaker Francis Howgilt, at his trial in Appleby said:

It has been a Doctrine always held by us, and a received principle…that Christ’s Kingdom could not be set up with carnal Weapons, nor the Gospel propagated by Force of Arms, nor the Church of God builded by Violence; but the Prince of Peace is manifest among us and we cannot learn War any more, but can love our Enemies, and forgive them that do Evil to us…This is the Truth, and if I had twenty lives, I would engage them all, that the Body of Quakers will never have any Hand in War, or Things of that Nature, that tend to the Hurt of others.

Following George Fox, the Quakers also opposed slavery and capital punishment.

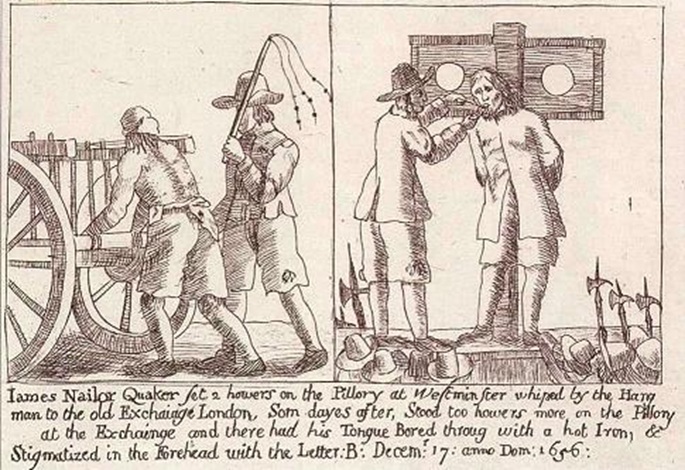

But if Quakers were so peaceable, why were they so persecuted in the 1650s, 1660s, 1670s and 1680s? Betrayed by local ‘informers’, arrested just for meeting to worship in silence in one another’s houses, or for refusing to attend their local church, they were heavily fined, imprisoned for months in filthy, stinking, dark holes – often below ground -, publicly stripped and whipped, stoned and even transported as slaves?. Under Charles II (1660- 1685), 13,562 Quakers were arrested and imprisoned; 198 were transported as slaves; at least 338 died in prison as a result of their injuries. It was in this same period that Bunyan the unlicensed Baptist preacher was in Bedford Jail and Richard Baxter, the Presbyterian minister who would not conform to the 39 Articles was tried in his frail and sick old age by the Chief Justice Judge Jeffreys. “What ailed the old stock-cole, unthankful villain, that he would not conform… He hath poisoned the world with his linsey wolsey doctrine”. Judge Jeffreys wanted the old man publicly whipped. But Baxter and Bunyan were individuals who were persecuted; the Quakers were persecuted as a collective body, an alternative, threatening counter- culture, a ‘Society of Friends’ that was a standing criticism of the wider dominant – and unfriendly – social fabric of Great Britain.

The Reasons for the persecution:

Quakers were seen as a threat to the given social order into which they had been born because they had many subversive beliefs and practices in addition to their refusal to bear arms. The refused to take their hats off in respect to ‘their betters’ because they were `no respecters of persons (cf. the Epistle of James above). This was not trivial; it was a traditional gesture of popular social protests and enraged ‘the better sort’. When one accused Quaker refused to take his hat off before the magistrate, the judge seized it, burned it and sentenced him to five months’ imprisonment.

Quakers refused to bow courteously or to use the polite terms of address; for instance they refused to say ‘You’ to their ‘betters’ but called everyone the familiar ‘Thou’, like ‘Du’ in German or ‘Tu’ in French. They refused to . give any of their fellow humans a special title. If they lived under a monarchy, they would not say ‘Your Majesty’ to the King, but just call him ‘King’; they would not say ‘My Lord’ to an aristocrat or ‘Your Honour’ to a Judge, or even refer to anyone as ‘Sir’ or ‘Lady’, ‘Mr’ or ‘Mrs’. Instead, everyone was simply called by their first name and surname and addressed as ‘Friend’ by Quakers – even Cromwell, when Lord Protector of England, was addressed as ‘Friend Oliver’ by Fox.

Quakers refused to swear any oath in a court of law because Christ had said ‘Swear not at all’. Again, in that same radical Epistle of James, we find : ‘above all things brethren, swear not, either by heaven, neither by the earth, either by any other oath: let your yea be yea; and your nay, nay. The truth was that everyone should speak everywhere and at all time, not merely in the witness box. But how could the non-oath taking Quakers be believed to be loyal citizens owing allegiance, or held capable of keeping any binding contracts, if they refused all oaths?

Quakers refused to have any parson or minister, believing instead in their own Inner Light, that which is of God in everyone; they refused even to attend Anglican church services, that is ‘the prescribed national worship’, let alone pay their local Anglican parson his ‘tithes’ or church rates, no matter how often and how grossly their own goods were thereupon ‘distrained’, looted; half of their confiscated property being taken by those who had informed against them. Quakers maintained that there should be no paid ‘hireling’ ministers in Britain at all, which did not endear them to the professional clergy. And who knew what sedition, or incitements their meetings in one another’s houses might not be brewing, asked the magistrates?

Finally, and perhaps worst of all in the eyes of their contemporaries, there even were many women Quakers, who followed their own Inner Light and preached in the streets as public missionaries who, when they were not in prison, travelled indefatigably throughout Britain and even the world, broadcasting the Quaker message of ‘that of God’ existing in every human being, including women.

Thus 17th century Quakers seemed to be threatening the creation of an alternative, much more egalitarian society, and one that even included the spiritual equality of men and women. Quakers would not conform to church or state. And they were making thousands of converts. Where might it not end if almost everyone turned Quakers? Social Revolution? Already by 1660, i.e. in their first eight years, there had been at least 20,000 converts. In 1653 George Fox wrote: ‘0 ye great men and rich men of earth! Weep and howl for your misery that is coming [quotation from the Epistle of James]…the day of the Lord is appearing… All the loftiness of men must be laid low’.

Alarmed, the Presbyterian Major-General Skipton, then in charge of London, had said in Parliament already in 1656: ‘[The Quakers’] great growth and increase is too notorious, both in England and Ireland; their principle strike at both ministry and magistracy’. It is not surprising, after all, that peaceable though they were, the Quakers were ruthlessly persecuted in an attempt to extirpate every one of them. How did they respond? They articulated their resistance, and testified to the principle of liberty of conscience.

Quaker History of the Persecution.

From the moment that they were persecuted, the late 17th century Quakers chronicled that persecution and their own un-budge-able, non-violent resistance. They wrote and printed pamphlets and letters to one another, above all to Margaret Fell, herself often imprisoned, and appealingly eloquently to the Magistrates, to King or to Parliament.

In 1660 Richard Hubberthom wrote ‘[If] any magistrate do that which is unrighteous, we must declare against it’. This the Quakers judged the magistrates, and their social ‘superiors’, not the other way round. In 1664, after the Conventicle Act, that sought to banish Quakers to the West Indies, George Whitehead, who has been called possibly the most influential advocate of religious liberty in Britain,2 ‘sheaved the judges their duty from the law and Magna Carta’. Every single example of arrest and punishment of Quakers was documented by a local Friend who could write a clear hand, naming both the local Sufferers and the local Persecutors on facing pages of their records.3

Thus Quaker solidarity and continuity was achieved through the creation of their own written accounts of individual and collective persecution. And it was upon these many local records, in addition to trial transcripts, that the amazingly comprehensive collective narrative compiled by Joseph Besse was based – The Suffering of the People Call Quakers for the Testimony of a Good Conscience 1650-1689. Thomas Paine was born precisely half way between these dates, in 1737.

Besse title page: If they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you (John). For the oppression of the poor, for the Sighing of the Needy, now I will arise, saith the Lord” (Psalms).

Besse’s Preface to the Reader:

‘It was an excellent observation… that God is tried in the fire, and acceptable Men in the Furnace of Adversity… Persecution is a severe test upon the Hypocrite and Earthly-minded. ‘When thou passest flub the Waters, I will be with thee..ffsalahr. A Measure of this holy Faith, and a sense of this divine Support; bore up the spirit of the People called Quakers for near 40 years together, to stem the Torrent of Opposition… The Messengers of it were entertained with Scorn and Derision, with Beatings, Buffetings, Stonings, Whippings and Imprisonment, Banishments, and even Death itself’

Just to give one vivid example of the persecution of a woman Quaker in Sussex there is the case of Mary Akehurst as summarised by Besse in his volume on Southern England, ch. 34, pp.711-712:

1659… Mary Akehurst, a religious Woman of Lewis [sic], going into a Steeple-house there, and asking a Question of the Independent Preacher, after his Sermon, was dragg’d out by the people, and afterwards beaten and puncht by her Husband, so that she could not lift her Arms to her Head without Paine. She also suffered much cruel Usage from her said Husband, who bound her Hand and Foot, and grievously abused her, for reproving one of the Priests who had falsely accused her. Her Husband also kept her chained for a Month together, Night and Day.

Mary Akehurst’s neighbours won her release by pinning a written protest about her treatment on the Church door. She continued to testify to her Quaker convictions, although even after her husband had died, she was punished by the authorities time and again. David Hitchin’s Quakers in Lewes (1984), based on the full account held in the Public Record Office Mary Akehurst’s neighbours won her release by pinning a written protest about her treatment on the Church door. She continued to testify to her Quaker convictions, although even after her husband had died, she was punished by the authorities time and again. David Hitchin’s Quakers in Lewes (1984), based on the full account held in the Public Record Office takes up the story: In 1670 she was distrained of goods worth £29 by false information. She appealed to the next Sessions and the informer, fearing be found a perjurer, fled. Her goods were ordered to be returned. In

1672 William Penn visited her in Lewes. In 1673 she was reported by an informer priest, William Snatt, for meeting in a private house, fined £8.10 shillings, and her goods were taken worth £16.18 shillings. In 1676 she was fined £10 for meeting in a house in West FirIe. In 1677 she was indicted for nine months’ absence from church. In 1686 (27 years after asking her first question in St. Michael’s church) when old, sick and unable to walk without being held up on either side, she was carried off at midnight by bailiffs to prison. In Besse’s words, op.cit. p.734:

One of the Bayliffs, being drunk, when he got on Horseback, with many Oaths and Threatenings had set her upon his Horse, and would not suffer her to take Necessaries with her, so that her Friends thought she could not live till she came to the Prison. But the barbarous Bayliff swore, that if she could not hold it to Prison, which was twenty Mlles, he would tie her, and drag her thither at his Horse’s Tail. Being brought to Horsham Jail, she was kept dose Prisoner there about seven Months, and then was removed to London and committed to the King’s Bench. In Oxford… In Cumbria…

It was men like George Fox, Francis Howgill, Edmund Burroughs, Richard Hubberthom, George Whitehead and Robert Barclay, and women like Margaret Fell, Ann Blaykling, Mary Fisher and Mary Akehurst who were Thomas Paine’s fearlessly radical 17th century forerunners, speaking out for justice and civil liberty, including liberty for (non-violent) non-conformity.

Part Two

Paine’s own Quaker Background.

Paine’s magisterial biographer John Keane stresses that Paine was the child of a mixed marriage – half Anglican, half Quaker and suggests that this must have led to his having a balanced, even detached, view of both orthodox and heterodox Christianity and hence to his championing of toleration. I myself see no reason to think that young Paine felt himself to be equally Anglican and Quaker. He is generally agreed to have been much closer to his Quaker father to whom he was apprenticed at thirteen than he was to his Anglican mother. And he actually recounts in The Age of Reason how shocked and alienated he had been when he was 7 or 8 years old, on hearing his Anglican aunt’s orthodox Anglican religious teaching of Original Sin and redemption through God’s allowing the crucifixion of his own son. Instead, when young Tom Paine attended Quaker meetings in Meeting House Lane, he would have heard Quaker neighbours testifying not to sin or damnation but to their feelings of love and unity and to the working of God’s mercy in their own lives; he would also have absorbed the practical mercy that Thetford Quakers gave out towards the needy, suffering members of their meeting.

For in Thetford, Quakers collective self-organization had already been established soon after the start of the first Friends’ meetings there.3

Through democratic ‘Quaker discipline’ that included ‘elders’ and ‘overseers’ and monthly, quarterly and yearly meetings as well as women’s meetings, taking care of the poor, the sick, the old, the widowed and the orphans had been the Quaker way from the first.4 Their path-breaking schemes of providing accommodation, weekly allowances, legacies and gifts of fuel and clothing (we again remember the Epistle of James) gave Paine a lifelong Quaker ‘feeling for the hard condition of others’ as he himself would write in his letter to the town of Lewes later. There would also have been (as there still is) decision-making by consensus – ‘the sense of the Meeting’. Therefore, despite arguments and some defections, and criticism, Quakers managed to practice democratic consultation and to avoid continuous acrimonious splitting into ever smaller groups. Instead, they tolerated different approaches to Truth if sincerely sought, trusting in each Friend’s own moral and reasoned judgement, as he or she followed their ‘Inner Light’.

We should also note that Quakerism is, and has always been, an outward looking faith. They believed from the first that Quakerism is something to be lived out in the world and this bonded them in shared efforts at humanitarian intervention. For the Quakers have never been short of others’ Sufferings’ that need addressing, the sufferings of slaves, prisoners, the disenfranchised, the starving, refugees, the victims of war and persecution.

Quakerism already had an influence on Paine’s schooling, between the ages of 7-13. His father said he must not learn Latin because of the books thro’ which that language is taught – think of the semi-divine status claimed for the founding of Rome in the Aeneid or the city or the deity accorded the later Roman emperors or Caesar’s triumph list history in his accounts of his conquest of Gaul. Simon Weil called history ‘believing the murderers at their own word’.

Did, during this period, young Paine read a copy of Besse’s Sufferings of the Early Quakers in the small Thetford Meeting House library? Or did his father, or a richer Quaker neighbour actually own a copy?5 We shall never know, but at the very least there must have been an inextinguishable orally transmitted tradition. As Sylvia Stevens writes in her monograph A Believing People in a Changing World: Quakers in Society in North-east Norfolk, 1690-1800:

When Friends such as Mary Kirby and Edmund Peckover who were directly descended from a Quaker of the first generation, gave their [oral] ministry, they were doing so as people who linked to the past but spoke a message for the present 18th century Norfolk Quakers acknowledged, shaped and revered their own religious pasts but lived in their own time.

What would young Thomas Paine have read or been told about the treatment of the Quakers, including his own kin, in Thetford, in Norwich and elsewhere in Norfolk, before he was born? And how would they have reacted?

The written history of persecution of Norfolk Quakers, especially Norwich and Thetford (Source: Besse)

1660 the deposition of Samuel Duncombe on the breaking up of a meeting in Norwich: ‘[We suffered their] smiting, punching, cruel mocking… thumping on the Back and Breast without Mercy, dragging some most inhumanly by the Hair of the Head, and spitting in our Faces, abusing both men and women…[They] have taken the Mire out of the Streets and have thrown it at the Friends, some of them holding the Maid of the House whilst others daubed her face with Gore and Dung, so as the skin of her face could hardly be seen.’

For that ‘scandalous expression’ Duncombe and the other Quakers were sent to prison. Whereupon Samuel Duncombe wrote again to the Mayor and Aldermen, beginning ‘Friends, Our Oppression is more than we ought always to bear in Silence. And now we are upon the brink of Ruin by the loss of our Goods,… made harbourless in our own houses… And what would you have us do? Do you think we are only wilful and resolve so to be? Do you think these things are pleasing to our own wills as creatures of flesh and blood as you are also, to suffer? You must also expect Judgement – therefore be not high-minded, but fear – for the Lord can quickly blast your Honour and disperse your Riches. We cannot sew Pillows under your armholes, but wish you well as we do ourselves.’

Duncombe later sent a second letter from Norwich prison, beginning not ‘Friends’, this time, but ‘Magistrates!’ And continuing: ‘For complaining of injustice our liberties are taken from us, we are forced to lodge in straw’.

In February 1665 at the Quarter Sessions held at Norwich Castle, Henry Kettle and Robert Eden both of Thetford, and two others, were convicted of the third offence in meeting together (see Conventicle Act) and were sentenced to be carried thence to Yarmouth, and from that Port to be transported for seven years to Barbados’ (i.e. as slaves). When Kettle returned after seven years, he was again arrested and imprisoned.

In 1676, William Gamham, Mary Townsend and Robert Spargin of Thetford were distrained of their good worth £2.5 shillings. One Captain Cropley molested them and attempted to disperse their religious meeting by Force of Arms. And when they asked for his commission so to do, he showed them his rapier. And one of them not going at his command, he beat him on the Head with his Stick and kickt him on the Back to the endangering of his Life.

November 1676, Samuel Dunscombe [again] reported how his house was forcibly entered; ‘officers bringing with them one Tennison and impudent Informer and the common Hangman. They tarried several days and nights in that home and kept Samuel Duncombe’s wife, then big with child, a Prisoner, suffering her to speak to no body and admitting none of the neighbours to come near her. The Goods they took were valued at £42.19 shillings’.

1678 ‘George Whitehead and Thomas Burr were taken at a meeting in Norwich. Charles Alden, a Vintner and one of the singing Men in the Cathedral, rushed in calling out ‘Here’s Sons of Whores; here’s 500 Sons and Daughters of Whores. The Church Doors stand open but they will be hanged before they will come in there’. sand whilst George Whitehead was speaking, [Alden] cryed out ‘Put down that Puppy Dog! Why do you suffer him to stand there prating?’

These Norfolk Quakers were then sent to prison in Norwich Castle and again in 1680 for refusing to take the oath. On his release George Whitehead went straight to Hampton Court to plead with the King on behalf of his fellow-prisoners left 27 steps below ground in Norwich Castle dungeons – ‘They are burying them alive’, he told the King, whom he just addressed as ‘King’, ‘They are poor harmless people, poor Woolcombers, Weavers and Tradesmen, like to be destroyed’. The prisoners were only released two years later.

1682 Anne Payne was committed to prison for ‘absence from National Worship’ (Many other Paines, or Paynes, in Norfolk suffered the seizure of their goods, and imprisonment).

1684 saw an ‘excessive Seizure from two Norfolk farmers, John Roe and William Roe, who were fined £240 and had all their cattle, corn and households goods taken by the Sherriff’s Officers in East Dereham. ‘The behaviour of the Officers and Assistants and who made this seizure was very rude. They broke open the Doors, Drawers and Chests and threatened the Servants of the House with Sword and Pistol. To make themselves merry they roasted a pigg and laid so much wood on the Hearth that they set the Chimney on Fire with which, and their Revelling, Cursing and Swearing, they affrighted the wife of the said William Roe to the endangering of her Life; she being then great with child, was delivered before her lime, and the child died a few days later’.

The persecution continued in Norfolk up to 1690. Such things are not soon forgotten. Whether or not young Thomas Paine, born in 1737, read a copy of Besse, so many were the oral accounts of the persecution period that he must have heard many examples from his father, from his paternal grand- parents and from other Thetford Quakers. It was still living memory and there can be no doubt at all on which side he and his father were on. It would simply not have been possible for him as a sensitive, spirited, indignant child and youth to have been equally pro-Anglican, on the side of the punishing ruling class, and on the side of their victims, the heroes and heroines of Quaker dissent.

Part Three

Paine’s writing on Quakers and on Quakerly principles.

1768-1775: Paine in Lewes.

Thomas ‘Clio’ Rickman, who would become Paine’s closest English friend and first devoted biographer (Paine would write part of the Rights of Man in his London home), first attached himself to Paine as his inspiring mentor when he was a youth in Lewes. ‘Clio’ Rickman was a ‘birthright’ Lewes Quaker on both sides of his family, the Rickmans being the dominant family in the meeting there. They first settled in Lewes around 1700 and were almost certainly related to, if not directly descended from, the Quakers Nicholas Rickman from Arundel who had been pitilessly persecuted in West Sussex decade after decade before 1690. Their common Quaker heritage and knowledge of Quaker persecution history would have been one of the bonds between the radical debating Paine of the Lewes Headstrong Club and his young admiring convert to radicalism, Rickman. ‘Clio’ Rickman himself would be disowned by the Lewes meeting for ‘marrying out’ but eventually died as a Quaker in London and would be buried in the Quaker burial ground in Bunhills Fields. He would publish Paine and give him sanctuary in London, and himself suffer as a publisher for his Paine connection.

1775-1787 America.

1775-80 Paine worked with Philadelphia Quakers in the first anti-slavery society in America, founded by the Quaker John Woolman. He wrote his first essay there asking the Americans to ‘discontinue and renounce’ slavery in African Slavery in America.

1775. In his Thoughts on a Defensive War, he wrote “I am thus far a Quaker, in that I would readily agree with all the world to lay aside the use of arms, and settle matters by negotiation: but unless the whole will, the matter ends, and I take up my musket”, i.e. against the troops, including Hessian mercenaries, being employed by the British to put down the American struggle for colonial independence – ‘laying a Country desolate with Fire and Sword (Common Sense).

Therefore, in 1776 in his Appendix to Common Sense, Paine opposed those conservative ‘Tory’, non-resisting Philadelphia Quakers who, in 1776, advocated reconciliation with the British King, Paine accused this group of rich Quakers, who, he said, did not represent all Quakers, of being not really neutral and peacefully above the conflict as they claimed by de facto partisans on King George III’s side, when they argued against resistance. Their very participation in political argument forfeited their claim to be apolitical quietists. They were really on the side of Mammon. Had Paine known of the actual degree of American Quaker economic collaboration with the British then going on behind the scenes, he would have been even more incensed.6

It is noteworthy that in the same Appendix Paine proves that he has read some Quaker persecution history in his admiring allusion to ‘the honest soul of [the Quaker Robert] Barclay’ and his quotation from Barclay’s Address to Charles 11, criticising persecution under Charles II, a King who having himself been oppressed ‘hest reason to know how hateful the oppressor is to both God and man’.

Xmas 1776 The American Crisis – first essay by Paine advocating total resistance even unto death: ‘These are the times that try men’s souls… Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered;…’ show your faith by your works’ (Epistle of James).

November 1778, 7th Crisis essay, Paine coined the phrase ‘Religion of Humanity’, i.e. humanity is the true religion. My religion is to do good’.

1788-9 and 1791: England.

1789 Letter to Kitty Nicholson:

There is a Quaker favourite of mine at New York, formerly Miss Watson of Philadelphia ; she is now married to Dr. Lawrence and is an acquaintance of Mrs. Oswald; so be kind as to make her a visit for me. You will like her conversation. She has a little of the Quaker primness – but of the pleasing kind about her.

1789 -1790 and 1792-1795: France

1793 attacked by Marat re clemency for King denounced for being a Quaker and therefore against death penalty.

1794 – 6: Paine on Quakers and Quakerism in The Age of Reason. Conway Introduction. Paine’s ‘Reason’ is only an expansion of the Quakers “inner light’. Paine was a spiritual successor of George Fox. He too had ‘apostolic fervour’.

Part 1, Ch. 1. The author’s profession of faith.

‘I believe the equality of man, and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow-creatures happy’. ‘My own mind is my own church’.

Ch.111. The character of Jesus.

‘He was a virtuous and amiable man. The morality he preached and practiced was of the most benevolent kind; and though similar systems of morality had been preached by Confucius, and by some Greek philosophers many years before, by the Quakers since, and by many good men in all ages, it has not been exceeded by any.

Ch. X111

My father being of the Quaker profession, it was my good fortune to have an exceedingly good moral education, and a tolerable stock of useful learning. Though I went to the grammar school, I did not learn Latin, not only because I had no inclination to learn languages, but because of the objection the Quakers have against the books in which the language is taught.

And note how his first attempts to think and write about politics and government were determined by the principle in which he had been raised – I.e. Quakerism.

The religion that approaches the nearest of all others to true Deism, in the moral and benign part thereof, is that professed by the Quakers: but they have contracted themselves too much by leaving the works of God out of their system. Though I reverence their philanthropy, I cannot help smiling at the conceit that if a Quaker could have been consulted at the creation, what a silent and drab-coloured creation it would have been! Not a flower would have blossomed its gaieties nor a bird been permitted to sing.

Part 2, Conclusion to The Age of Reason:

The only sect that has not persecuted are the Quakers; and the only reason that can be given for it is, that they are rather Deists than Christians. They do not believe much about Jesus Christ, and they call all scriptures a dead letter.

1797, Letter to Camille Jordan who was anxious to restore Catholic privileges, inc. church bells, in post-revolutionary France.

The intellectual part of religion is a private affair between every man and his Maker, and which no third party has any right to interfere. The practical part consists in our doing good to each other. But since religion has been made into a trade, the practical part has been made to consist of ceremonies performed by men called priests; true religion has been banished; and such means have been found out to extract money even from the pockets of the poor, instead of contributing to their relief…

No man ought to make a living by Religion. It is dishonest to do so. Religion is not an act that can be performed by proxy. One person cannot act religion for another… that can be performed by proxy. One person cannot act religion for another…

The only people who, as a professional sect of Christians provide for the poor of their society, are people known by the name of Quakers. These men have no priests. They assemble quietly in their places of meeting, and do not disturb their neighbours with shows and noise of bells… Quakers are equally remarkable for the education of their children. I am a descendent of a family of that profession; my father was a Quaker, and I presume I may be admitted as evidence of what I assert. … Principles of humanity, of sociability, and sound instruction for advancement of society, are the first objects of studies among the Quakers… One good schoolmaster is of more use than a hundred priests.

1803, Letter to Samuel Adams.

…”the World has been overrun with fables and creeds of human invention, with sectaries of whole nations against all other nations, and sectaries of those sectaries in each of them against each other. Every sectary, except the Quakers, has been a persecutor. Those who fled from persecution were persecuted in their turn.

1804, Prospect Papers.

It is an established principle with the Quakers not to shed blood, Re revelation: the O.T. usage ‘the word of the Lord came to such a one – like the expression used by a Quakers, that ‘the spirit moveth him”.

The Quakers are a people more moral in their conduct than the people of other sectaries, and generally allowed to be so, do not hold the Bible (i.e. the O.T.) to be the word of God. They call it ‘a history of the times’.

Conclusion

Paine himself was not a Quaker, because he was not a Christian and the Quakers were Christians, however unorthodox and radical. Nevertheless, his Quaker heritage from his father gave him a birthright example of principled, fundamental criticism of the corrupt, caste-ridden, unjust society into which he was born.

The persecution history, in particular, of his Quaker forebears transmitted to Paine both by word of mouth and in print in his youth, must, I believe, have been truly inspirational ‘strengthening medicine’ as he in his turn dared to ‘speak truth to power’. There is no foundation for conviction like saeva indignatio. And Paine, like the early Quakers, would also face trial for ‘sedition’, would be exiled by a fearful aristocratic government and would be imprisoned and risk death for his convictions – the latter, ironically, at the hand of revolutionary extremists.

Paine acknowledged the idea rightness of the Quaker Peace testimony and would only ever see justification in a purely defensive armed struggle. Paine helped start the American Quaker campaign in Philadelphia to abolish slavery and the slave trade.

Paine remembered the Society of Friends’ organization of care for its weakest members as a template for the possibility of organized social welfare that he would expound in Rights of Man. His allusions to Quakerism and the practice of the Quakers in his writings whether in America„ in France or in England, were overwhelmingly respectful, even at time reverential – ‘I reverence their philanthropy’.

So far I have implied the influence of Quakerism on Paine was as positive as it was profound. But was it wholly positive? Perhaps we should consider the comment made by the eighty year old portrait painted by James Northcote, himself a political liberal, as reported in Hazlitt’s first Conversation with Northcote, in 1829.

Nobody can deny that [Paine] was a very fine writer and a very sensible man.

But he flew in the face of a whole generation; and no wonder that they were too much for him, and that his name became a byword with such multitudes, for no other reason than that he did not care what offence he gave them by contradicting all their most inveterate prejudices. If you insult a room-full of people, you will be kicked out of it. So neither will the world at large be insulted with impunity. If you tell a whole country that they are fools and knaves, they will not return the compliment by crying you up as the peak of wisdom and honesty. Nor will those who come after be very apt to take up your quarrel. It was not so much Paine’s being a republican or an unbeliever, as the manner in which he brought his opinions forward (which showed self-conceit and a want of feeling) that subjected him to obloquy. People did not like the temper of the man.

The first Quakers had certainly known how to get up the noses of their late 17th century persecutor. They knew they were in the right, that they were ‘the Children of God’ and those who were against them were mere ‘hirelings’ and ‘worldlings’. But they did not thereby endear themselves to their world. As Besse himself said: Nor could it be expected that a Testimony levelled both against the darling Vices of the Laity and the forced maintenance of the Clergy should meet with any other than an unkind reception.7 Was Paine too much like those earliest Quakers, forfeiting persuasiveness in the certainty of his own exclusive rightness – and so ‘[meeting] an unkind reception’?

Twenty years earlier than Hazlitt’s Conversation about him with Northcote, on his deathbed in March,1809, Paine had expressed his last wish:

“I know not if the Society of people called Quakers, admit a person to be buried in their burying ground, who does not belong to their Society, but if they do, or will admit me, I would prefer being buried there; my father belonged to that profession, and I was partly brought up in it.”

According to Keane, a local New Jersey Friend, Willett Hicks:

‘conveyed Paine’s request sympathetically to the local Friends, but it was refused. Hicks reported back that the society felt that Paine’s own friends and sympathizers “might wish to raise a monument to his memory, which being contrary to their rules, would render it inconvenient to them”….Paine sobbed uncontrollably’ …

Notes

- Conway, Moncure, Life of Thomas Paine…. 1892, vol.1, p. 11.

- See Oxford DNB entry on Whitehead, See Public Record Offices for the earliest mss. Quaker archives, listing local ‘Sufferers’ and ‘Perpetrators on facing pages, month by month, year by year, 1652-1690.

- Those among the Valiant Sixty’ at Firbank Fell in 1651 who had gone to ‘ publish truth’ in Norwich and Norfolk in 1653-4 pi included Christopher Atkinson from Kendal, Ann Blaylding from Drawell, Richard Hubberthome from Yealand, James Lancaster from Walney, Dorothy Waugh from Preston Patrick and George Whitehead from Orton.

- Keane p. 24: they believed their mutual aid enabled them to return in Spirit to the grace of the earliest ‘primitive’ Christians.

- Quote intro. to facsimile of Besse re their distribution.

- See Conway, vol.1, pp. 78-77.

- Besse, Introduction.