By P. O’Brien

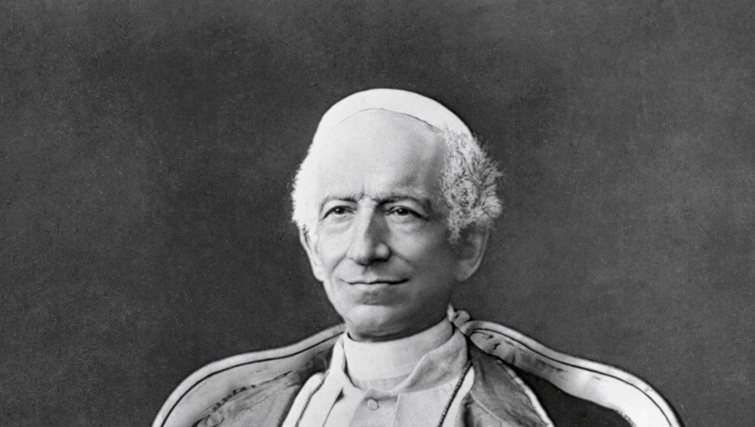

Last December my wife and I moved from a sizable bungalow to a flat for oldies (sheltered accommodation). Losing our loft necessitated shedding many books and loads of paper going back many years – the accumulation of an indiscriminate hoarder! There are still box loads which have yet to be pruned to yield further fascinating discoveries. One recent treasure to emerge was a slim booklet (price twopence) of 51 pages, which I had studied in late schooldays, more than sixty years ago. It was an encyclical Letter emanating from Pope Leo XIII entitled Rerum Novarurn, with the English subtitle, The Workers Charter, published in 1891. I still remember being impressed with it at the time (probably 1939).

With great interest I again read the opening paragraph and, in the light of other material studied since then, my immediate reaction was: “That could have come from the pen of Thomas Paine”. Then I noticed the date; 1891 was the centenary of Rights of Man. Could this mean that the Pope, or one of his advisers, being familiar with Paine’s work, and considering relevant changes through the intervening century, decided that the time was ripe for reassessment and fresh recommendations?

I have gone back to Rights of Man and compared it carefully with The Workers Charter. I would find it hard to believe that this new work, coming on the centenary of Paine’s, was merely coincidence and of no further significance. But, although there is evidence, I cannot assert proof. It has been suggested to me that this is another instance of Paine being plagiarised, as he was by Edmund Burke, but this is not so, because nowhere in the papal document is Paine quoted either with or without acknowledgement.

So let us consider the writing and leave readers to reach their own conclusions, either from what I present, or from studying the original texts which are still readily available. But, first let us consider why the papacy might fail to acknowledge a philosophic debt to Paine. Christian denominations in general were affronted by his publication in 1793-95 of The Age of Reason and ceased to rate what he had previously achieved. So it might have been considered poor tactics for the Vatican to acknowledge him at that time.

The Age of Reason which adopted the Deist philosophy of Robespierre and other French philosophers was highly critical of Judeo-Christian scripture, although Paine’s background was certainly Christian and his Rights of Man reflects this. His mother was Anglican, the church in which he was baptised, confirmed and married. His father was a Quaker and he writes of: the affectionate and moral remonstrance of a good father. In early days at Grantham he heard John Wesley preach and followed him for a time into Methodism as a lay preacher, hoping to be ordained, but in this he was stymied due to his lack of Latin and Greek. Later, after experience in America and France he would proclaim, “My country is the world and my religion is to do good”; whilst criticising “governments, putting themselves beyond the law as well of God as of Man”.

There can be no doubt as to his moral approach in considering the ills besetting society at that time, and most of this is to be found in Rights of Man, Part II, chapter 5, ‘Ways and Means’, where his opening comment is on ‘widespread poverty and wretchedness…. in countries that are called civilised we see age going to the workhouse and youth to the gallows…. Why is it that scarcely any are executed but the poor? Bred up without morals, and cast upon the world without a prospect, they are the exposed sacrifice of vice and legal barbarity’.

He blames much on inequity in taxation by saying that, ‘Civilised relationships between nations could reduce taxation’. Poor Rates he saw as a direct tax with a considerable part of its revenue expended in litigation, ‘in which the poor, instead of being relieved are tormented’. These rates effect the labourer who ‘is not sensible of this, because it is disguised to him in the articles which he buys’. Is this so different from the VAT we have today, which inevitably falls most heavily on the poorest in society since many essentials cannot be purchased without paying up? He goes on to comment that ‘the poor are generally composed of large families of children and old people past their labour’. He pleads for `good provision for primary education’, also to address ‘problems of the aged, ex-soldiers, worn out servants, poor widows and middling tradesmen’. This should be a matter of ‘enlightened support… and not a matter of grace and favour’.

Then he summarises his major recommendations: Family allowance, old age pensions, a marriage grant, maternity benefit, a death grant for funeral expenses, provision for the casual poor in inner cities (our cardboard cities today), Army and Navy pensions, provision for widows with children to maintain, and Education for all, commenting that: ‘It is monarchical and aristocratic government only that requires ignorance for its support,… Many a youth comes up to London with little or no money, and unless he gets immediate employment he is already undone…. Hunger is not among the postponable wants.’

Finally, returning to worship and belief he reviews his own situation: `Why may we not suppose that the great Father of all is pleased with variety in devotion’ (he would surely welcome today’s ecumenicism).’I am fully pleased with what I am now now doing, with an endeavour to conciliate mankind, to render his condition happy, to unite nations that have hitherto been enemies… to break the chains of slavery and oppression, is acceptable in His sight, and being the best service I can perform, I act it cheerfully’.

In Rights of Man Part I, in his ‘Observation on the Declaration of Rights’ by the French National Assembly, he comments on the query raised: whether the tenth article sufficiently guarantees the right it is intended to accord with. This article states that: no man ought to be molested on account of his opinions, provided his avowal of them does not disturb the public order established by law. He then comments, ‘It takes off from the divine dignity of religion and weakens its operative force upon the mind, to make it a subject of human laws’, adding in a significant footnote:

`There is a single idea which, if it strikes rightly upon the mind either in a legal sense, will prevent any man, or any body of men, or any government, from going wrong on the subject of religion which is that before any institution of government was known in the world there existed, if I may so express it, a compact between God. and Man, from the beginning of time; and that as the relation and condition which man in his individual person stands in towards his Maker, cannot be changed, or anyway altered by any human laws or human authority, that as religious devotion, which is part of this compact, cannot be made subject of human laws; and that all laws must conform themselves to this prior existing compact, and not assume to make the compact conform to the laws, which besides being human, are subsequent thereto. The first act of man, when he looked around and saw himself a creature which he did not make, and a world furnished for his reception, must have been devotion, and a devotion must ever continue sacred to every man, as it appears right to him; and governments do mischief by interfering’.

He also touches lightly on Workmen’s Wages, a topic scarcely considered in society generally at that time and where he had his own very bitter experience, when his first pamphlet, The Case of the Officers of Excise (1772), caused him to he dismissed from that service, whose members had no Association to argue for their rights, so that his campaign was largely single-handed. He stood alone and could be swept aside!

So how does all this impinge on Pope Leo XIII in 1891 with his Workers’ Charter? Much had changed in the course of a century, but much still remained for the following century. We start where his thesis has just left off with Worker’s Rights and the need for Organised Labour, since that is where his Encyclical kicks off, considering: ‘The fortunes of the few and poverty of the masses’, the need for ‘self reliance and mutual combination of workers…relative rights and mutual duties of rich and poor, capital and labour’, then commenting on ‘ the ‘misery and wretchedness’ experienced by a ‘majority of the working class’ due to the `hard heartedness of employers…greed of unchecked competition by covetous and grasping men…little better than slavery itself.

Next comes a note of caution regarding Socialism which is ‘striving to do away with private property’ and warning that the ‘working man… would be the first to suffer’. But here there is obvious confusion between what we now regard as Socialism and atheistic Communism, and remembering that the Russian Revolution is still some decade ahead, we can understand that the far sighted Paine would never have approved of Stalin’s system. The Charter asserts the ‘motive if work is to obtain property’ 2hich it sees as ‘necessary for maintenance and educa- tion…every man having by nature the right to possess property as his own. … For man… being master of his own acts, guides his way under the eternal law and power of God. … Man precedes the State…and there is no-one who does not sustain life from what the land produces… providing that private ownership is in accordance with the law of nature…the results of labour should belong to those who have bestowed their labour’. But we should question whether if labour is bestowed on behalf of an employer the produce should then belong to the labourer? Paine would hardly have gone that far.

‘A father should provide food and necessities for those he has begotten… but extreme necessity should be met by public aid. … Paternal authority can neither be abolished nor absorbed by the state’. The Charter goes on to assert that ‘the child belongs to the father’, but modern theology surely rejects such an extreme view, and would concede that a father who fails in his responsibility or abuses his child must, in extreme cases, give way to properly constituted, caring authority. What would Paine say?

The Charter, as we would expect, has much to say on the role of the Church, and in particular in upholding the rights of labour, asserting that ‘men will be vain if they leave out the Church’. However, there have been times when the Church has lapsed into a state of decadence, and lost its authority. Paine, in France during the Revolution, was well aware of this, as were many others. It is worth consulting Hilaire Belloc’s small tract on the French Revolution. A firm Catholic himself and born in France (though with an English mother, descended from Joseph Priestley) he strongly asserts the Church was merely reaping what it had sown through autocracy, arrogance and the aristocratic attitude of hierarchy, hand-in-glove with aristocracy. However, by the end of the 19th century much had changed and Pope Leo was standing on firmer ground. His Charter asserts that ‘the Church improves and betters the conditions of working men by means of various organisations’.

However, it is ‘impossible to reduce society to one dead level. …People differ in capacity, etc.’, although this is a ‘mistaken notion that class is naturally hostile to class. …Religion teaches the wealthy owner and employer that work people are not bondsmen. …Labour for wages is not a thing to be ashamed of. …Employers must never tax workers beyond their strength, nor employ them in work unsuited to sex or age. …Man should not consider his material possessions as his own, but as common to all, so as to share them without hesitation when others are in need…giving to the indigent out of what is over…remembering that: It is more blessed to give than to receive (Acts XX:35). Christian morality…leads to temporal prosperity…restrains greed for possessions and thirst for pleasure’.

`Safety of commonwealth is government’s reason for existence. …When the general interest of any particular class suffers…public authority must step in. …Rights must be religiously respected. …It is the duty of the public authority to prevent and punish injury, and to protect everyone in the possession of his own. …The richer class have many ways of shielding themselves’.

Next the issue of Strikes is addressed: ‘The chief thing is the duty of safeguarding private property by legal enactment of protection. Most of all it is essential, where passion of greed is so strong, to keep people within the line of duty, for if all may strive to better their condition, neither justice nor the common good allows any individual to seize upon that which belongs to another, or, under the futile and shallow pretext of equality, to lay violent hands upon other people’s possessions. Most true is that by far the larger part of the workers prefer to better themselves by honest labour rather than by doing any wrong to others. But there are not a few who are imbued with evil principles and eager for revolutionary change, whose main purpose is to stir up disorder and incite their fellows to acts of violence. …When working-people have recourse to strike it is frequently because the hours of labour are too long, or the work too hard, or because they consider their wages insufficient. The grave inconvenience of this is not uncommon occurrence and should be obviated by public remedial measures; for such paralysing of labour, not only effects the masters and their work-people alike, but is extremely injurious to trade and to the general interests of the public. …The laws should forestall and prevent such troubles from arising; they should lend their influence and authority to the removal, in good time, of the causes which lead to such conflicts’.

It is also important, ‘to save unfortunate working-people from the cruelty of men of greed, who use human beings as mere instruments of money making. …Those who work in mines and quarries should have shorter hours in proportion as their labour is more severe and trying to health. …In regard to children care should be taken not to place them in workshops and factories until their bodies and minds are sufficiently developed’. In general, ‘proper rest should be allowed for soul and body’. And there is an ‘obligation of the cessation of work on the Sabbath’.

A Living Wage: ‘…Without the result of labour a man cannot live, and self-preservation is a law of nature’. A Just Wage: `Let the working man and the employer make free agreements. …Wages ought not to be insufficient to support a frugal and well behave wage earner. …Circumstances, times and localities vary widely, for example, hours of labour in different trades, the sanitary conditions to be observed in factories and workshops. …Thus it is advisable that recourse should be had to (appropriate) Societies and Boards’.

`The law should favour ownership and its policy should be to induce as many as possible to become owners. …Property will become more equitably divided. …The result of civil change and revolution has been to divide society. …On one side is the party which holds power because it holds wealth…on the other is the needy and powerless multitude. …Men always work harder and more readily when they work on that which belongs to them…provided that a man’s means be not drained by excessive taxation’.

The Encyclical turns next to: ‘Societies for mutual help and benevolent foundations established by private persons to provide for the workmen and his widow or orphans in case of sudden calamity, in sickness and in the event of death, institutions for the welfare of youngsters and the elderly’. Then to Trade Unions: ‘Most important are Working Men’s Unions. …History attests what excellent results were brought about by the Artificers Guilds of olden times. …It is gratifying to know that there are not a few associations of this kind (at present) consisting of workmen alone, or of workmen and employers together’. Then, quoting Holy Writ: ‘Woe to him that is alone, for when he failed’ he has none to lift him up’ (Ecclesiastics IV:10). And further, ‘A brother that is helped by his brother is like a strong city’ (Proverbs XVIII:19).

Next, on doubtful organisations: …’Many of these societies are in the hands if secret leaders, and are managed on principles ill-according to Christianity and the public well being; and that they do their utmost to get within their grasp the whole field of labour, forcing men either to join them or starve’. Then to the contrary influence of religion: ‘…that Gospel, which by inculcating self restrain, keeps men within the bounds of moderation, and tends to establish harmony among the divergent interests and the various classes which compose the state. …There are not wanting Catholics blessed with affluence, who have cast in their lot with the wage-earners, and who have spent large sums in founding and widely spreading Benefit and Insurance Societies, by which the working man may acquire…the certainty of honourable support in days to come. … Working-men’s associations should be so organised and governed as to furnish the best and most suitable means of attaining what is aimed at…for helping each individual member to better his condition’.

In the relevant Societies, ‘It is important that the office bearers be appointed with due prudence and discretion’, to ensure that ‘difference in degree or standing should not interfere with unanimity and goodwill. …Prejudice is mighty and so is the greed of money’.

Then in final summary: ‘…Masters and wealthy owners must be mindful of their duty; the working-class, whose interests are at stake, should make every lawful and proper effort. …The main thing needful is to return to real Christianity. …All must earnestly cherish in themselves, and try to arouse in others, charity…which is the fulfilling of the whole Gospel law, which is always ready to sacrifice itself for others’ sake, and is man’s surest antidote against worldly pride and immoderate love of self. Then, rounding off with a quotation from St.Paul on Charity, which simply means Love: ‘Charity is patient, is kind, …seeketh not her own…suffereth all things…endureth all things’ (I Corinthians XIII:4-7).

A true appeal for tolerance and understanding.

It is inevitable that readers will react in a variety of ways to what has been presented here, and it must be appreciated that the material has had to be edited, and considerably and selectively reduced, but with material from both sources which, not surprisingly, has its own bias. The aim has been not to introduce any fresh bias, but to present the extracted text as truly and as simply as the task demanded. Then, in the final analysis, any and every reader can search out the original texts to verify what has been on offer. I myself have a high regard for both Thomas Paine and Pope Leo; I would not wish deliberately to misrepresent either.