By Terry Liddle

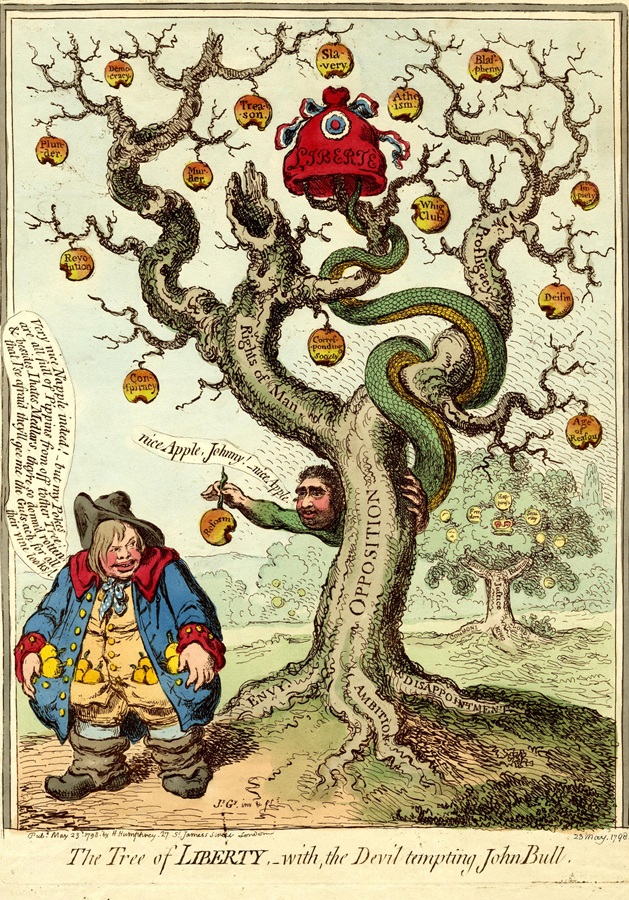

Described By Richard Carlile as ‘…the first serious and honest attack ever made upon the Christian Idolatry in this country’ Paine’s, Age of Reason was written during his stay in Paris. The second part was penned in the Luxemburg prison where Paine faced a strong possibility of execution. Luckily, he survived and like his earlier Rights of Man, The Age of Reason had a large scale impact on radical thought, an impact which continues to this day. According to the bishop of London, Cornish miners were reading The Age of Reason while a government spy reported its warm reception in Liverpool. It was found in the pockets of rebellious United Irishmen in 1798.

Francis Place, the living link between the Jacobins of the 1790s and the Chartists of the 1830s, read The Age of Reason while waiting for his wife to give birth in 1794. So impressed was he that he sought out the book’s owner, a member of the London Corresponding Society, and himself joined the society. Such was the controversy provoked by The Age of Reason in the London Corresponding Society’s ranks that those who opposed Atheism and Deism broke away to form a new organisation.

Another who at this time read Paine and came under his influence was Eton pupil, Percy Shelley. In 1811 Shelley publish his, The Necessity of Atheism- In a sense he was lucky, the only penalties he suffered were . expulsion from Oxford University and the end of his father’s allowance. In 1814 he wrote, A Refutation of Deism. Shelley was greatly admired by Carlile who devoted a considerable space in the Republican to a discussion of his work. When the High Court condemned Shelley’s Queen Mab as seditious and blasphemous and the publisher burned his stock, Carlile rushed out his own edition. Sadly, Shelley never saw it, and within months he drowned in Italy.

Falling on hard times, Place hoped to improve his finances by publishing an edition of The Age of Reason. In this he enlisted the aid of an impoverished bookbinder Thomas Williams. Anxious to keep the profit for himself, Williams cut Place out of the deal. Thus it was upon the head of Williams that the wrath of the establishment fell. In June 1797 he was tried before Lord Kenyon for having sold a single copy of part two of The Age of Reason, the prosecutor in this case being Robert Erskine who some years before had brilliantly defended Paine’s Rights of Man. On the grounds that Christianity was part of the law of the land and any attack upon it was therefore illegal, Williams, a sock man, was sentenced to a year in prison. On hearing the sentence, Williams asked if he might be allowed a bed in prison. Lord Kenyon replied that he could not order that as the publication in question was ‘horrible to the ears of Christians’.

The prosecution of Williams had been instigated by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. The society’s aim was the imposition of piety upon the poor by outlawing their pleasures, intellectual or otherwise. The ban on Sunday meetings which charged admission was the society’s work. The Vice Society, as it was popularly known, floundered when it sought legislation to imprison adulterers. To ban the pleasures of the poor was one thing, to interfere with those of the rich just was not on.

A leading figure in the vice Society was William Wilberforce, a Tory Member of Parliament and friend of William Pitt and an ardent anti-slavery campaigner. William Cobbett launched a furious attack on him for championing slaves in the West Indies while ignoring the wretched plight of labourers at home. Wrote Cobbett, ‘…what an insult to call upon people under the name of free British labourers; to appeal to them on behalf of black slaves, when these free British labourers, these poor, mocked, degraded wretches, would be happy to lick the dishes and bowls out of which these Black slaves have breakfasted, dined and supped’. He continued, ‘…it is notorious that great numbers of your free British labourers have actually died of starvation’.

When Erskine discovered that Williams’s family was starving and the children suffering from smallpox, he urged the Vice Society to exercise Christian mercy and content itself with the time Williams had spent in Newgate awaiting sentence. It declined. So angered was Erskine that he returned his fee and declined any further contact with the society.

In 1812 the bookseller Daniel Eaton was tried for having published a collection of Paine’s essays which he called part three of The Age of Reason. This was described as an impious libel representing Jesus as an imposter. Although he was aged sixty and in poor health, Eaton was awarded eighteen months and to stand in the pillory once a month. Such was the public outrage at this that the pillory fell into disuse.

Richard Carlile had The Age of Reason during one of his numerous stays in prison and decided to publish his own edition. This appeared in a half guinea edition in 1818. Having exited the ire of the authorities by his reporting the massacre by the yeomanry of demonstrators for reform in Manchester he was brought to trial in October 1819 on a charge of blasphemous libel for having published The Age of Reason. Once again it was the Vice Society which had instigated the proceedings.

The trial lasted three days Carlile defending himself in a marathon eleven hour speech in which he read aloud the whole of The Age of Reason thereby ensuring it would be included in the record. He also published the trial proceedings as a two penny [pamphlet. The judge, Chief Justice Abbot, commented that it was no defence to repeat the libel complained of.

Carlile complained that proceedings in the trial were irregular and not in accordance to law and that therefore the verdict was contaminated. He protested the authority of the court to try the charge of blasphemy in that no person had been defamed. It was, he said, alleged that he had incurred the wrath of the Almighty, but no proof of this had been offered. He sought to prove to the jury that his intentions were good, not wicked and malicious as charged, by showing the truth and moral tendency of the book he had published.

Carlile attempted to call as witnesses ‘The Archbishop of Canterbury, the High Priest of the Jews and the Astronomer Royal, with the most eminent men in each Christian Sect, to shew to the jury that Christianity could not be part of the law of the land, as Christianity could not possibly be defined and no man could possibly say what it really was…’ However, the Lord Chief Justice would not let him do this.

After hearing a discourse on the virtues of Christianity and the demerits of its opponents from the Lord Chief Justice, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Carlile received three years imprisonment and a fine of £1,500. Unable, and unwilling, to pay the fine, Carlile was obliged to spend a further three years behind bars, remaining in Dorchester prison until 1826. However, such were the peculiarities of the penal system of the time that he was able to continue editing his newspaper, The Republican, from his prison cell.

Carlile’s place as publisher of The Age of Reason was taken by his wife Jane. She, too, was imprisoned, part of the charge against her being the sale of W.T.Sherwin’s biography of Paine, receiving two years imprison- ment. As a married woman she was considered to have no property and so was not fined. She was followed by Carlile’s sister, Mary Ann, who received two years imprisonment and a fine of £500.

Carlile’s supporters formed themselves into Zetetical societies, many of them volunteering to keep Carlile’s Fleet Street shop, the grandly named Temple of Reason, from which The Age of Reason and similar publications were sold. Not a few suffered imprisonment as a result. With the rise of Chartism and its unstamped press (a stamp duty had been imposed on papers to price them beyond the reach of the poor) some of them would end up behind bars for upholding the freedom of publication. The Carlile case was the last prosecution of The Age of Reason, but it would be a long time before radicals could publish and distribute their publications without fear of legal penalty.

In prison Carlile wrote a long biographical essay on Paine. Of The Age of Reason he wrote: `It was written in France expressly to stem the torrent of French atheism… Its purpose was bourgeois and reactionary rather than radical and proletarian. …it contained truth and truth will not be confined to a nation or to a continent. But it will tend to fail as a standard criticism of superstition precisely because it is not atheistic’.

In 1819 William Cobbett had returned from the United States bringing with him Paine’s bones. His aim in so doing was to atone for his youthful attacks on Paine by erecting a mausoleum which would be a place of radical pilgrimage. It did not happen and after Cobbett’s death the bones were lost.

It was Carlile who established the tradition of celebrating Paine’s birthday. The Republican of February 22, 1822, reported a gathering of Stockport republicans to celebrate the ‘natal day of Mr-Paine’. Nearly seventy years later the National Reformer was reporting a children’s tea party on Paine’s birthday organised by the West. Ham branch of the National Secular Society.

Paine was a great influence on the Chartists. When it was founded in 1837 the East London Democratic Association stated its object was: ‘…to promote the Moral and Political conditions of the working classes by disseminating the principles propagated by that great philosopher and redeemer of mankind, the Immortal Thomas Paine’. Bronterre O’Brian urged Chartists to read Paine along with Locke because ‘they will tell you labour is the only genuine property’.

Today we live in an age of fanatical fundamentalism and theocratic intolerance. Even in the supposed democracies there are those who would willingly censor the reading of ordinary folk. Two centuries after its publication, The Age of Reason remains necessary reading for freethinkers and radicals. And we should never forget those such as Carlile who strove and suffered to make it available when to do so was extremely dangerous.