By P. O’Brien

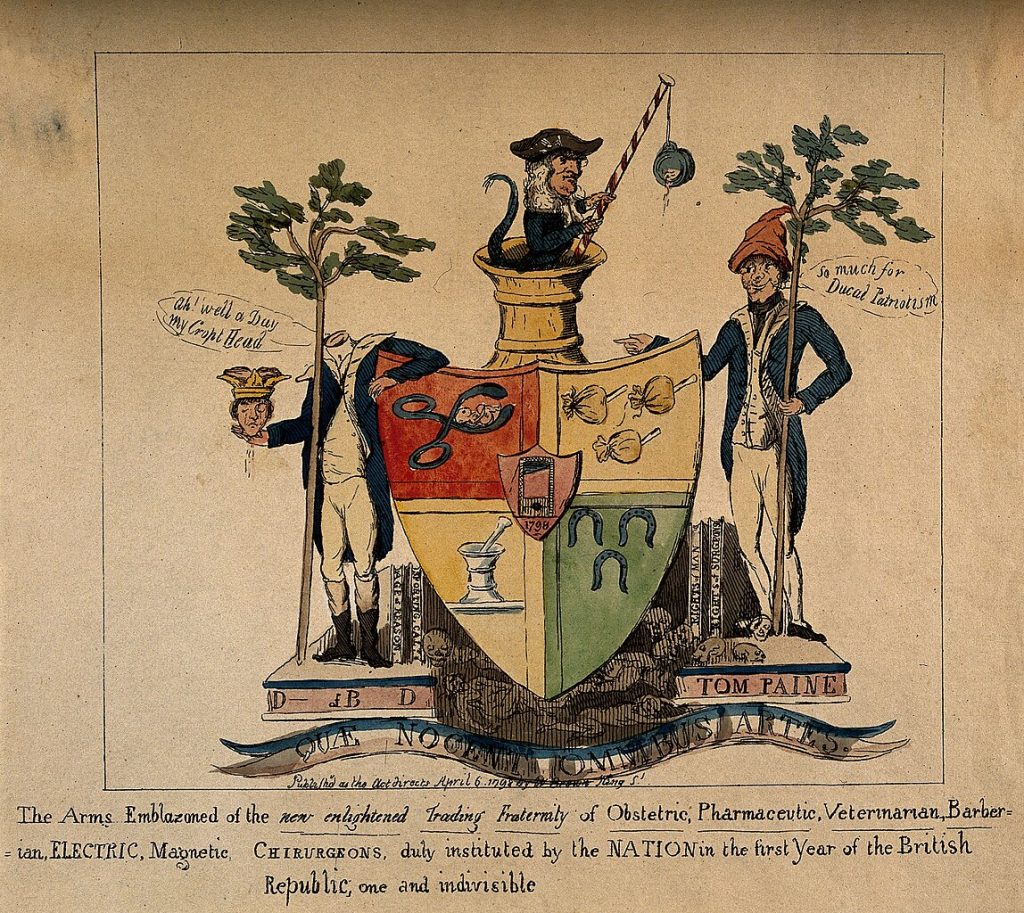

There has been much discussion in recent months, and many letters published, about which outstanding British person should occupy the vacant plinth in Trafalgar Square. It so happened in one week that two Norfolk contemporaries, Admiral Nelson and Thomas Paine, were put forward at the same time and there was little doubt which way the majority of Britons would have voted. Every schoolboy knows Nelson’s achievements; after all winning battles is what really matters, is it not? More senior teenagers would know of other achievements. But in his day Paine led his own nation, as well as America, France and others, to think radically on the ways in which society should function. His greatest work, Rights of Man, sold hundreds of thousands of copies right across the western world, bringing people at all levels of society together to study and discuss its many advanced views.

Paine’s thinking influenced social evolution relentlessly, although much too slowly, during the 19th century and on into the 20th, but his own nation has largely forgotten him and all that it owes to him; America is much more aware. His last major publication, The Age of Reason, must take a large share of the blame for this. It is not so much that he adopted a deist philosophy, it is the extraordinarily ill informed and hateful way in which he attacked Christianity, and Judaism before it. Christians of all denominations were affronted and disgusted, even the Quakers whom he singles out to exclude from his general condemnation, when he requested burial in their cemetery, refused.

When we consider Paine’s personal in detail it is difficult to understand how he could have published such a work, even allowing that he was heavily influenced by deist leaders of the French Revolution in its degenerative stage, overwhelmed and stressed by the threat to his own life when he was imprisoned for daring to vote against sending Louis XVI to the guillotine.

Paine was born into a family of practising Christians. His mother was an Anglican, ensuring that he was baptise, confirmed and twice married in that communion, but his father was a Quaker and obviously had a profound influence upon his faith. In early life he wrote of, ‘the ef- fectionate and moral remonstrance of a good father’. Most signifi- cantly, as he was reaching maturity, he was to come under the spell of John Wesley and, as a result of hearing him preach, he engaged as a Methodist preacher in several locations. It has in recent times been asserted that he aimed to be ordained as a Methodist minister. (*George Hindmarsh. ‘Thomas Paine: The Methodist Influence’. TPS Bulletin. March, 1979.)

At that stage there were no separately ordained Methodists, since Wesley never regarded himself as anything other than Church of England, though taking a rather independent line. Paine himself, as officially Church of England, could have been ordained apart from one gap in his education. When he had reached grammar school his father decreed that he was not to learn Latin, which he associated primarily with Roman Catholicism. Without Latin Paine could not enter one of the English universities, the only path to ordination. How different his whole career might have been had this been otherwise. We might never have had Rights of Man let alone The Age of Reason, although it would be surprising if he had not published significant work on human rights and social development, considering his broad interest in these subjects.

Looking at the 18th century in England overall, we see the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, with rural workers migrating to new manufacturing towns where they were soon being grounded down by ambitious mill owners and other leading industrialists, making them savage and illiterate in ways that were later illustrated in novels by Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, and others. The established church took little interest in saving these people until John Wesley came along to convert and civilise, producing what we may now see as ‘articulate artisans’. Without Wesley the 1790s might well have seen bloody revolution throughout England following the example of France. Instead, those whom he had encouraged to know and read sacred scripture were well to read relevant social works such as Rights of Man when they came to hand, boosting Paine’s sales to such an extraordinary extent.

Those who have a formal education, in which they consider to be superior institutions, are always ready to demean those whom they regard as their less fortunate fellows, but they miss the point that people with superior intelligence will acquire an appropriate education by one means or another. And so it was with Thomas Paine, particularly when he moved to Lewes in Sussex, where he was soon drafted onto the Town Council. However, a more important factor was the Headstrong Club based in a local hostelry, somewhat akin to Rotary, Probus or similar organisations today, where he associated with experienced, educated and well read individuals. As his knowledge grew, a certain arrogance began to manifest itself from early on, as for instance when he declared after Common Sense had been published in America, “I scarcely ever quote, the reason is I always think”. And this attitude manifests itself again when he tackles The Age of Reason.

It is interesting to compare Paine’s experience in Paris during the Reign of Terror with what Charles Dickens reveals in A Tale of Two Cities when dealing with the same problems. Dickens had a great gift for exploring complex social attitudes and developments as well as presenting fascinating, albeit fictional, characters. Sydney Carton was one of these, who had certain things in common with Paine in his later days. Both had resorted to a heavy reliance to alcohol to combat stress, and almost certainly had similar reflections when facing the end of life.

Sydney Carton was contemplating a tremendous self-sacrifice which could bring him to the guillotine, in the interest of very dear friends, one of whom would himself escape as a result of what Carton was prepared to undertake.

[It is a far better thing I do than I have ever done. It is a far better rest I go on to than I have ever known.]

He reflects upon his ‘vagabond and restless habits’ remembering that ‘he had been famous among his earliest competitors as a youth of great promise’ up until his father’s death. He remembered solemn words which had been read at his father’s grave:

I am the resurrection and the life saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and he who liveth and believeth in me, shall never die.

It was the end of a fateful day as he looks upon –

…the lighted windows where the people were going to rest, forgetful through a few calm hours of the horrors surrounding them; in the towers of the churches, where no prayers were said, for the popular revulsion had even travelled that length of self destruction from years of priestly impostors, plunderers and profligates; in the distant burial-places reserved, as they wrote upon the gates, for eternal sleep.

As he moves along the phrase, ‘I am the resurrection and the life’ keeps haunting him, while remembering his father. It is repeated three times.

Not far off Thomas Paine would have been lying in his prison cell, another victim of ‘The Reign of Terror’, contemplating his own pos- sibly imminent journey to a likely conclusion. Was he reflecting on. ‘the affectionate and moral remonstrances of a good father’? Probably not, if he was already involved in composing The Age of Reason, but years later, retired back in America, when he appealed to the Quakers to inter him in their cemetery, can we be sure that his thoughts were not similar to those of Sydney Garton? Who can say?

In composing Rights ofMan Paine is assessing a social structure with which he had become very familiar, looking at its weakness, as well as some strengths, then going on to point out ways in which reformation and improvements may be achieved. He had thought long and hard, so he was writing with confidence.

When it comes to The Age of Reason however, this is a man floundering and lashing about in a sphere where he was entitled, like all of us, to have his own views, but hardly to foist them upon a public at large, many of whom, because of his excellent reputation up to that point, would regard him as a potential expert in almost anything to which he might put his mind.

When we associate with people of faith across a wide spectrum of Christian denominations it soon becomes apparent that faith may be strong without a detailed knowledge and study of scripture. As Paine discovered, when he had access to a Bible for part two of The Age of Reason, apparent contradictions rise up to challenge us which are not always easy to resolve. To start with, the concept of Revelation does not feature strongly with him, as it challenges the Deism which by then he had firmly adopted.

It is not the purpose of this presentation to go through the publication in detail, but a few outstanding examples will hopefully serve to illustrate its weaknesses. Starting with the Old Testament he shows little knowledge of Judaism; he is not well informed on the oral tradition of earlier times, faithfully handed down from generation to generation until written records take over first in Hebrew, then in Greek and Latin, resulting in slightly different printed versions over time. He has particular difficulty with prophets and prophecy; he sees them as primitive poets acting on the side, not scribes, nor priests. It is commonplace to regard them as individuals predicting the future. He has no appreciation that where with hindsight we now see some prophecy in that way, the actual prophet may not himself have appreciated the full meaning of what he was proclaiming.

This is well illustrated in Luke’s book of Acts where he gives an account of the apostle Philip’s meeting with a eunuch, an officer from the Queen of Ethiopia’s court returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The man was reading a passage from Isaiah (53:7-8): “Like a sheep that is led to the slaughter; like a lamb that is dumb in front of its shearers,…He never opens his mouth. He has been humiliated and has no-one to defend Him. Who will ever talk about His descendants, since His life on earth has been cut short?”

The eunuch asks Philip, “Is the prophet referring to himself or to someone else?” From that point Philip explained to him the good news of Jesus, which was there predicted. The eunuch was converted and sought baptism. The prophecy had been fulfilled centuries after Isaiah and Philip was expounding it years after the trial and death of Jesus.

Prophets were inspired individuals, who might occasionally be priests but most frequently were critics of God’s people and the leaders who were taking them astray. Good examples are Nathan when he confronts King David with his sin against Uriah the Hittite, so that he may add Bathsheba to his tally of wives and concubines, or Elijah when he is overcoming the prophets of Baal, then pursuing King Ahab and Queen Jezebel at the risk of his own life and welfare, feeling mightily threatened and depressed.

Coming to the New Testament, Paine sees the four evangelists, authors of the Gospels, as four of the twelve apostles of Jesus, a not uncommon misconception throughout Christianity even today, and of little consequence for many, but for Paine the idea was misleading. He regards the Gospels as if they were all written in or about the same time by individuals who had lived with Jesus to the end of his earthly life. In his own experience as a journalist, such a group of contemporary reporters should vary little.

In fact the position was quite different, only two were apostles of Jesus, Matthew was one of the earliest to write and John was the last who, at the end of a long life, with much to cogitate, seeing the synoptic gospels already in place, accounting for the life and actions of Jesus, wanted to present His teaching in greater detail. The other two, Mark and Luke, were companions of Paul, so their perceptions would be influenced by him. Luke was a convert from paganism, a Roman citizen, a physician studying at Alexandria, but with a keen perception of Judaism and what was happening at its heart just then. If Paine had appreciated all this he would have been much less confused.

Some of his off-the-cuff comments on New Testament details are intemperate and highly offensive to sincere Christians as, for instance, what he has to say on the virgin birth, and on the life of Jesus. He rubbishes Jesus, Mary and Joseph as genuine historical characters, which of course enemies have done down through two millennia.

To conclude, our Thomas Paine Society undoubtedly has members who cherish his Age of Reason, their undoubted right, but can they deny that it has damaged Rights of Man for many others? A sad out- come for such an outstanding social reformer, and his work.

References

John Keane. Tom Paine – A Political Life. London, Bloomsbury, 1995.